Following The Film Stage’s collective top 50 films of 2025, as part of our year-end coverage, our contributors are sharing their personal top 10 lists.

My feelings from the intro of my top ten of 2024 haven’t changed much. I found 2025 to have a fair amount of good films, but only a few got a strong reaction out of me. I don’t say this to be some sort of fussy contrarian. I admit that I might be too demanding or stubborn, but I find myself increasingly dissatisfied with the overpraised competence of most new films. Like I said in 2024, I don’t see much risk or imagination, and in an industry that’s feeling more precarious than ever I think those things correlate.

To be clear, that’s an industry problem more than an issue with the films. What’s becoming clearer to me with each year is that the function of the festival circuit to highlight the best of world cinema is largely broken, partly due to the fact that business interests have become more dominant within those spaces. That aspect makes me pessimistic, but I can’t put that on the artists who are simply trying to navigate and sustain a career under those conditions.

So here are ten films and five honorable mentions from 2025, all of them worth seeking out.

Honorable Mentions: One Battle After Another, The Christophers, Two Pianos, Predators, Magellan

10. Reflection in a Dead Diamond (Hélène Cattet and Bruno Forzani)

Hélène Cattet and Bruno Forzani’s films could easily be dismissed as vibes-based genre riffs, given their heavy reliance on style over logic in works like Amer and Let the Corpses Tan. But Cattet and Forzani’s methods shouldn’t be reduced to mood exercises. They take the familiar elements of European genre cinema, then twist, distort, and stretch them to the breaking point. With Reflection in a Dead Diamond, their experimentation takes on a more profound meaning as it’s contextualized through the perspective of an elderly, retired spy whose memories blend reality and Eurospy fantasy. As always with Cattet and Forzani, their boundless creative expressions and homages make for an entertaining spectacle, the kind of cinematic overindulgence that’s so good you can forgive them for biting off more than they can chew.

9. Dry Leaf (Alexandre Koberidze)

The title of Alexandre Koberidze’s latest film should come with an asterisk, since every mention of Dry Leaf has to include the fact that it was shot on a 2000s cell phone in a low resolution. It’s also worth mentioning that the film clocks in at just over three hours and, after its opening half hour sets up a road trip a father takes to find his missing daughter, much of Dry Leaf unfolds in a series of montages of Georgian villages and soccer fields. That doesn’t sound like one of the most engaging films of the year, but Koberidze’s use of his old, pixellated camera demands constant interaction with his film’s blocky, textured imagery to figure out what exactly we’re looking at from one shot to the next. Coupled with the film’s melancholic tone as its protagonist observes the changing landscape of his country (and we observe through outdated technology), Koberidze’s low-budget, “low-quality” film is one of the year’s most affirming examples of what films can achieve with even the smallest resources.

8. The Mastermind (Kelly Reichardt)

Broadly speaking, Kelly Reichardt’s The Mastermind sees her telling another story of a person who, in their attempts to break free from one kind of prison, winds up guaranteeing a worse fate for themselves. This time she sets her story in 1970, where tensions over the Vietnam War rise in the background while an unemployed husband and father evades police after a botched art heist. And while the scruffy charms of Josh O’Connor’s protagonist help him get out of some jams, Reichardt keeps the focus away from his own motivations while taking note of how the consequences of his actions impact those around him. O’Connor’s character would see The Mastermind as a slick crime film, but Reichardt lets it play out like a slow-motion chase between its immature lead and everything he tries (and fails) to keep in the periphery. As it goes with Reichardt’s films, not everyone was a fan of her singular take on the heist movie, but I found plenty to enjoy in her dry, funny takedown of a person who discovers the hard way that the personal and political aren’t parallel lines.

7. With Hasan in Gaza (Kamal Aljafari)

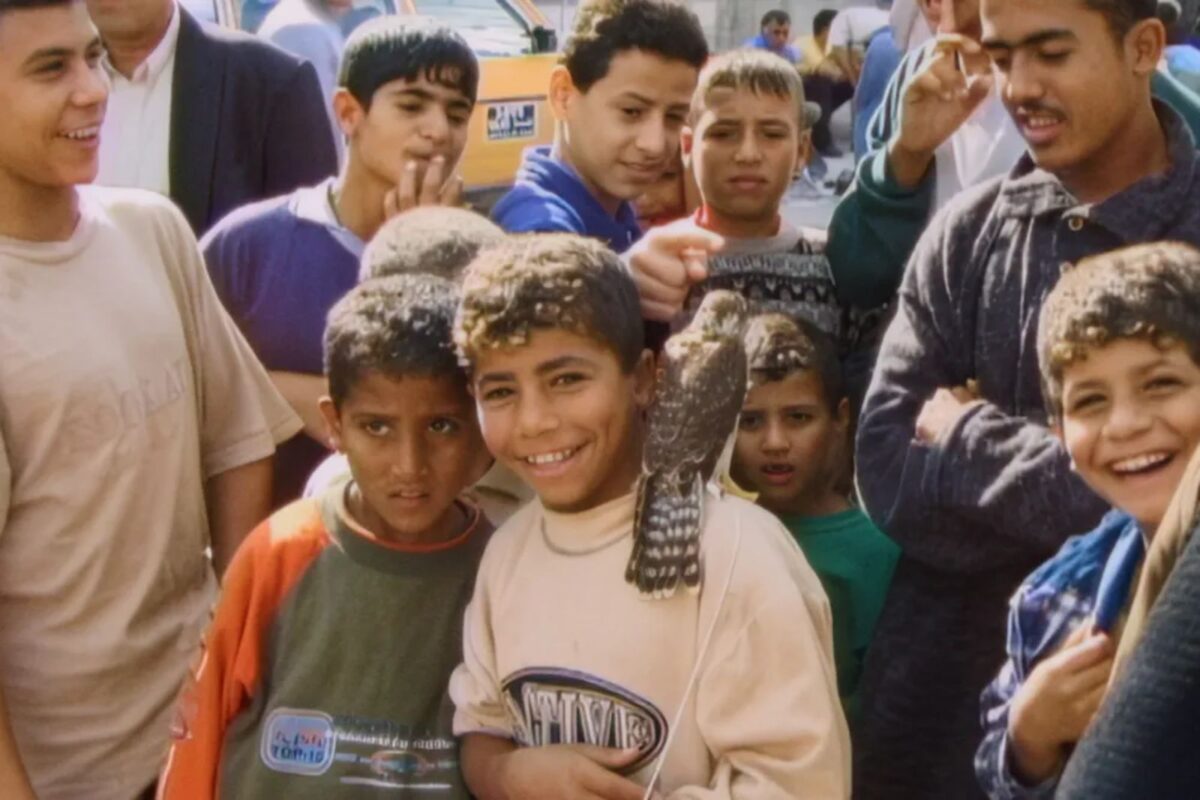

The existence of With Hasan in Gaza was an accident. When going through his archives to find the original footage from his first feature, Kamal Aljafari discovered three MiniDV tapes from 2001 when he took a trip to Gaza in the hopes of finding a cellmate from his time in prison as a teenager. Aljafari presents the tapes in full, chronological order, documenting his harrowing experience visiting Gaza more than two decades before the ongoing decimation and genocide in the region. Aljafari first presents the footage as a raw document of a Gaza that no longer exists, with an increasingly oppressive and violent presence of the Israeli military as he travels further into Gaza. But it’s in the film’s final section, where Aljafari reflects on his own memories in response to revisiting his tapes, that With Hasan in Gaza becomes a moving statement on the necessity and power of remembering.

6. Sound of Falling (Mascha Schilinski)

The word I often use to describe Mascha Schilinski’s Sound of Falling is slippery because, as formally audacious as her direction is, it’s hard to get a firm grasp on what her film does. There are four storylines, all set at the same rural farmhouse in Germany across generations and decades, although it’s hard to parse out the direct links between characters and plotlines. Schilinski hops back and forth between each story, and within that shuffles between perspectives and narrators at a moment’s notice. The lack of strong footing for viewers makes Sound of Falling disarming, with the only things to grab on to often being moments or lines that recur like echoes. But there’s no doubt that Schilinski is in total control, as the elusive qualities of her film pair nicely with its central characters figuring out their own sense of self while becoming aware of the (often predatory) gaze of those around them.

5. Miroirs No. 3 (Christian Petzold)

I’ve seen the word “minor” used to describe Christian Petzold’s Miroirs No. 3, which I assume is a shorthand dismissal without having to explain much further as to why this particular Vertigo remix doesn’t work as well as his others. But I found this to be an excellent return to form after Afire, with Petzold going back to the well of ghosts, Hitchcock, and doubles to pull off another excellent drama, one told with the kind of precision, control, and economy that I wish almost every director working today could learn from. I won’t say more about Miroirs given it works best knowing as little as possible, to let the dreamlike quality of its opening act establish mysteries that gradually reveal the sadder and human truths hiding between the lines.

4. Barrio Triste (Stillz)

I said plenty about why Barrio Triste is one of the best films of the year in my review from earlier this year, so I’d recommend giving that a read if you’d like to know more. One thing that’s stuck out to me since watching the film is how much it stands apart from Harmony Korine’s films AGGRO DR1FT and Baby Invasion, both from Korine’s new company EDGLRD that produced Barrio Triste. Korine’s films take inspiration from video games and use tech like generative AI to seek out what he describes as something “post-cinema,” although his freewheeling and juvenile approach makes it hard to find where the startup tech demo ends and art begins. Stillz’s first person horror/sci-fi/action/found footage movie takes on a personal quality in its examination of lost teenagers in 1980s Colombia, highlighting the chaos of their lives as much as it follows them aimlessly wandering around their neighborhood, aware they have no future to look forward to. Stillz’s immersive and crackling portrait of these young characters has a beating heart that Korine’s films lacked, but as long as EDGLRD keeps giving new names like Stillz the chance to experiment like this, I’ll be there for whatever they do next.

3. Sirāt (Oliver Laxe)

Sirāt is this high on my list but I’m not happy about it. I admit that Oliver Laxe’s film is one of the best directed things I’ve seen all year, that it contains more than one showstopping sequence, an incredible score, and moments so visceral it brought me back to the arthouse shock films that used to be a dime a dozen at Cannes over a decade ago. I also admit that, in hindsight, the film feels somewhat flimsy and arbitrary in its setup, its WWIII backdrop providing an instability that lets it get away with its more ludicrous elements. There’s also the fact that Sirāt is a cruel film, concocting grueling punishments for its characters that would make Michel Franco proud. But as much as I hate to admit it, I had fun. Part of it probably had to do with Laxe having the directorial chops to make his film’s spiritual aims work, creating just the right conditions in the middle of nowhere to paint on a cosmic scale. So I have to hand it to Sirāt, a film so good at slapping me in the face I have no choice but to respect it.

2. Father Mother Sister Brother (Jim Jarmusch)

After his last feature The Dead Don’t Die ended the world with a shrug, Jim Jarmusch is back in low-key territory with Father Mother Sister Brother, a triptych about different families in different parts of the world spending the day together. Like Jarmusch’s best films, there’s an enjoyment in the effortlessness he brings as a writer and director, how he can gather some of the best actors working today to make some of the most assured and cool things you’d see in a given year or decade. But Father Mother Sister Brother offers much more in its examination of familial bonds, letting each story’s negative space sketch out a relatable portrait of strained relations, where the obligation of interacting with your immediate family can sometimes come with the heavy lifting of a lifetime of resentment. It’s all beautifully done, with the final act offering a touching relief to the awkward comedy of the first two stories in its glimpse at two siblings dealing with the loss of their parents.

1. A Balcony in Limoges (Jérôme Reybaud)

Every year, people will try to find which films speak to our current moment, an exercise that I usually find pointless. For 2025, two films I saw popping up as movies “of our time” were Ari Aster’s Eddington and Paul Thomas Anderson’s One Battle After Another. The former was nothing more than bad, smug satire; the latter was far more entertaining, although its adjacent universe setting and focus on passing the spirit of revolution from one generation to the next made it too broad to feel especially urgent. For me, the only film from 2025 to feel like it had any understanding of the moment we find ourselves in as a culture and society was Jérôme Reybaud’s A Balcony in Limoges.

Reybaud observes a chance meeting between two former classmates who are now middle-aged women. Eugénie, a single mother who’s proud of being a “good citizen,” crosses paths with Gladys, who chooses to be homeless and rejects everything about society. Reybaud distills these two women into representations of two dominant types of people living today. Eugénie represents those still clinging on to a neoliberal status quo that’s on life support, while Gladys symbolizes the angry rejection of that status quo that’s led to the rise of far-right populism. A Balcony in Limoges watches the two women clash, with Eugénie thinking she can “rescue” Gladys, whose selfish and destructive behavior doubles as a middle finger to everything Eugénie believes in. It’s a conflict that Reybaud uses to point out that both women have the same problem of living under a failing world order, except they’re too stuck in their ways to see what unites them. How that conflict resolves is shocking and funny, a bit of pitch-black comedy that summarizes the inevitable outcome of our inability to imagine a better world for ourselves. Hopefully more people will get to discover A Balcony in Limoges for themselves if it ever gets distribution in North America, as its provocative and succinct take on how the last ten years have felt is better than any other film I’ve seen from 2025.