It’s easy to divide David Lynch’s career into sections of surprising commercial accessibility and complete mainstream alienation — the cultural breakthrough of Twin Peaks being the best representation of the former, the borderline solipsistic experimentation of Inland Empire standing in for the latter. This notwithstanding, to place his 1990 feature, Wild at Heart — a highly abrasive, yet emotionally sincere road movie — within the Lynch filmography reveals less about mainstream acceptance and something more concrete about an ideology.

Based on Barry Gifford’s novel of the same name, Wild at Heart traces a somewhat familiar two-young-lovers-on-the-run narrative. This iteration concerns Sailor (Nicolas Cage) and Lula (Laura Dern), the both of whom flee from her mother, Marietta (Diane Ladd), who’d already before placed a hit on him that ended in a murderous self-defense which briefly placed him in jail. A failed attempt won’t stop Marietta, who hires her hangdog boyfriend, P.I. Johnny Farragut (Harry Dean Stanton), to track them down, while also pegging the far-more-nefarious criminal mastermind Marcellus Santos (J.E. Freeman) for a second attempt on Sailor’s life.

As Wild at Heart’s narrative very blatantly bears the mark of a number of prior noir tales, it’s important to remember that David Lynch has never hid from pop culture, often to the point of making his characters blatantly interact with it — from Frank Booth crying at a lip-synched performance of Roy Orbison’s “In Dreams” to the characters of Twin Peaks doing the same for any time Julee Cruise showed up at the The Road House. A character’s specific relationship to it is most thoroughly articulated in the 1990 picture, with Sailor, Lula, and all their surrounding freakshows constantly imitating or projecting their idols, with the two dominant motifs being Elvis Presley and The Wizard of Oz — two items of popular culture that every American citizen is familiar with.

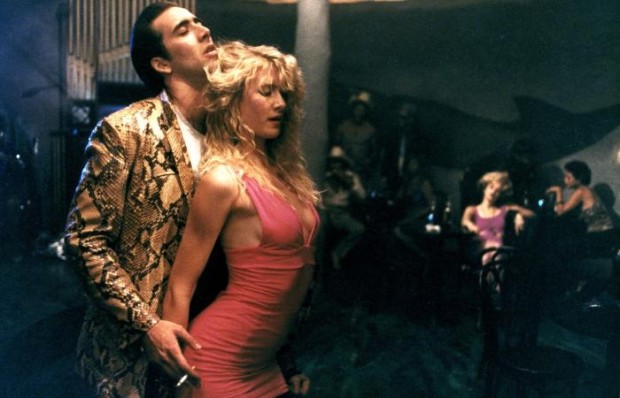

In turn, Wild at Heart finds itself primarily concerned with the construction of personal mythologies, perhaps the chief example being Sailor and his trademark snakeskin jacket, its donning in spaces both private and public accompanied by a monologue about how it represents his belief in individuality and personal freedom. (Even Lula chidingly mentions that she’s heard this about a million times already.) Of course, integral to these personal mythologies is the act of storytelling: Sailor and Lula provide backstory upon backstory about their troubled pasts that all naturally explain why these two damaged outcasts are perfect for each other. The film’s editing patterns make images from their stories (flaming homes, crying faces) bleed in and out when nobody is making so much as the slightest reference to them, giving the overriding feeling that their future will likely end up the same as their past.

It’s not so much a film of unreliable narrators, though, being that it always seems to believe entirely in its characters’ convictions. While reviews by Jonathan Rosenbaum and Roger Ebert took both them and the tone as wholly insincere, Lynch obviously loves his performers and their world too much to truly mock. There’s a definite joy he takes in Cage and Dern’s physical performances, as with a match-cut of Lula’s legs thrusting up and down on their motel bed to her actual dance with Sailor in a club.

This very sequence leads to his performance of Elvis’s “Love Me,” which manages to leave all other visitors of this distinctly late-’80s club rapt. That the members of the metal band in the background would support Sailor in his impromptu number may actually be the strangest sequence in a film already containing a cameo by Crispin Glover as an estranged, Christmas-obsessed cousin who puts cockroaches in his underwear. It suggests, in that instant, that the universe of the film is one solely created by its two leads, but Lynch, at one point countering that, distinctly plays God: Sailor and Lula pull over in the middle of nowhere to do a variety of wild, kung-fu-like gyrations to their favorite metal tune, only for a crane shot to pull away from them and reveal the landscape, at which point the soundtrack transitions to regular Lynch collaborator Angelo Badalamenti’s typically dreamy score.

The film’s clash isn’t just in music, but also narrative: while Sailor and Lula’s story is a relatively simple road-movie tale, Marietta’s is that of convoluted noir with multiple hit men and their grotesque worlds of disguises and whorehouses. While certainly familiar territory considering the vast ensemble and equal convolution of Twin Peaks, it’s still, perhaps, the closest Lynch has ever come to Fritz Lang or Louis Feuillade, with multiple criminal networks the motives of which seem to extend far beyond placing a hit on some young troublemaker — this, all to the point that the special edition DVD released in 2004 came with an outline of every character and their supposed motivation or connection to the primary couple. Of course, Lynch’s work is no stranger to such business: Mulholland Drive’s DVD was famously accompanied by the “10 Clues to Unlocking This Thriller” insert, and Dune’s theatrical release notoriously came with a sheet explaining every term from Frank Herbert’s convoluted mythology.

Beyond the comparably dense narrative, however, placing Wild at Heart in the Twin Peaks mindset only reveals similar strategies in handling characters. Lula and Marietta (played by real life mother and daughter Diane Ladd and Laura Dern) instantly brings to mind the troubled parent-daughter relationship in series prequel Fire Walk With Me. (Lula envisioning Marietta as a wicked witch flying on her broom, mapping the mother’s face onto a monster, is not at all unlike Leland Palmer and the demonic Killer BOB.) In fact, Twin Peaks and The Wizard of Oz even have similar divisions of good and evil — the lodges for the former, the witches for the latter.

As much as Wild at Heart makes its pop-culture text apparent, it, like Fire Walk With Me, is just as much a film about dread. Sailor and Lula verbalize their worries about bad omens and hexes placed on them throughout the second half, in one case after witnessing the aftermath of a teenage car accident — as if, within their notions of themselves and their story, there lies a natural end, in some sense potentially a comeuppance for their misdeeds. Their car radio even spells doom at one point, with talk radio reporting stories of murder and necrophilia while Lula searches in desperation for some actual music, which had been absent at no previous point in their journey. By the time the film reaches its climactic bank heist, Lynch cross-cuts between the two in their separate places, essentially forming a psychic link as they reach a simultaneous awareness that the bank heist Sailor agreed to (out of desperation) is going to go wrong.

For all reasons, Sailor and Lula likely should’ve died in the heat of passion (or stupidity), yet like how Tony Scott altered the ending of another early-’90s couple on the run film, True Romance, so that the young lovers who writer Quentin Tarantino wanted to kill could actually live, it finds a far more optimistic resolution. While Gifford’s original ending had them living but breaking up — if anything, a more devastating conclusion for these two — Lynch didn’t see that as befitting the characters he clearly loved so much. This would seem suspect, being that Blue Velvet quickly subverted its “love conquers all” ending with a reminder of the evil still left underneath small-town America — but, in this film, a landscape that had always been more ostensibly sinister and death-ridden (or, in Lula’s own words, “wild at heart and weird on top”) at least rewards its couple with another moment in which they seemingly make the entire world stop. Of course, it’s all for a second Elvis song.

Wild at Heart is now available on Blu-ray.