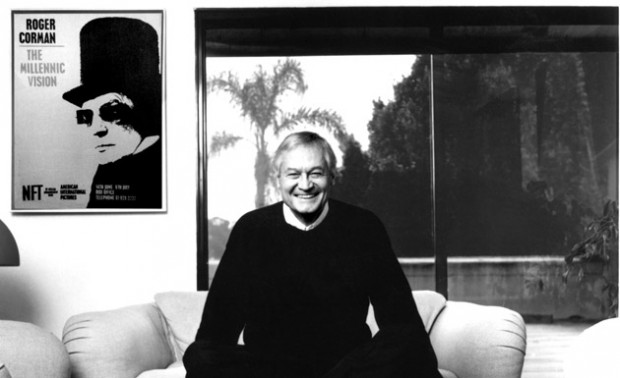

I was recently afforded the opportunity to talk to Alex Stapleton, the director of the wonderful documentary Corman’s World: Exploits of a Hollywood Rebel (review here) about the many sides of the “schlock king” Roger Corman. Through a tenuous phone connection (I do have an AT&T iPhone and live in New York City, after all), we discussed the process of making this film, how she got roped into doing crew on a Corman movie, Jack Nicholson‘s lounging gear, and doing interviews from the barber’s chair. The Film Stage’s questions are in bold, Alex’s responses follow.

Is there going to be a big premiere out there?

Well we had our kind of fancy premiere at LACMA [Los Angeles County Museum of Art], actually as a part of Film Independent’s series that they were running with Elvis Mitchell. So that was kind of our fancy night. So we will have on the 16th of December, for opening night, I guess you’d call it, [a Q&A] with Roger [Corman] that will be a lot of fun. But there won’t be a red carpet or anything like that.

You mentioned doing a Q&A with Roger, how receptive was he to be a part of this movie?

You mentioned doing a Q&A with Roger, how receptive was he to be a part of this movie?

We went through phases, I guess you could call it. Setting up the film was actually a very odd thing because most people that I had spoken are kind of like, “oh my god, what did you do?” You know, [I] felt like a director before, but I didn’t have any directing credits, but I managed to pull it off. With Roger, I simply asked him to do the film, and I didn’t know him. I interviewed him for a magazine, I was writing film articles for a magazine at the time, and I did a story on him and right after the interview I asked him if he was interested in having a documentary chronicle his life, and that I wanted to direct it and make it. He said yes. And I think he said “yes” not quite understanding how serious I was and how committed I was going to become to do this full, in depth look at his life.

So initially he said, “yes,” but we weren’t in that much contact. And then as I started to gain momentum with the project he got more excited about it, I guess, so he’s always been supportive of me and the movie. But from early on he said that he wanted nothing to do [with] contacting people, putting me in touch with people like Jack [Nicholson] or Peter Fonda, Bruce Dern or any of these guys. It was just too embarrassing, I think, to say, “hey, come participate in a documentary about me.”

“Come talk about how great I am!”

Exactly, exactly. And Roger’s just not that guy. It’s just not his personality. So there was always a separation of church and state in that regard. And also just creatively he was from day one, I guess that was the cool thing about him being a film maker himself, and being a film maker who had other people tamper with his final product, or his vision, because he’s been burned in the past, he was very respectful to me as a film maker in allowing me to tell the story that I wanted to say. So it was good.

I think the biggest criticism was at a certain point I had the movie at about 100 minutes, the [cut] that we showed at Sundance, and we came back to LA and he was like, “Alex, it’s a good film, but you could actually cut some time out,” which I wanted to do anyway. So he gave me some notes. Not to take out stories or people but just some trims here and there. It was kind of exciting to work with him, to get this page of notes from him. “You should cut three frames here, and go into this scene faster.” So that was cool.

Was the article itself the impetus for the film? Did you research that and want to extrapolate from there?

I was a Roger Corman fan prior to writing the article, and the genesis of the idea, I guess, was that I grew up watching a lot of his movies that were on TV in the ’80s. At 19, I got my hands on his autobiography, How I Made A Hundred Movies In Hollywood And Never Lost A Dime and it became my bible, because I never had the chance to go to film school. I had three or maybe five books that I went to all of the time to get inspired by or just to understand the mechanics of film making.

When I read his book I was completely floored that one person, one guy was responsible for so many different genres and so many different types of movies that I really loved. Not only that, but he was responsible for launching the careers of so many film makers that I adored; I was just really impressed. I think, at that point, I probably had the idea that this would make for a really good doc; this story should be told.

My career had progressed and it got to a point where I was producing feature-length documentaries and I wanted to branch out and start directing and to do my own story. When I want in to the reserves of my brain to think about what I could do, I was like, “oh my god, I should do a documentary about Roger Corman!” No one had done it since the late ’70s, and that’s how it started.

It was kind of challenging because I didn’t know him and I didn’t know anyone who knew him, and I was living in Brooklyn at the time, completely away from the LA scene. I figured, how was I going to get started? And I thought maybe if I interview him first, meet him and just introduce myself and do an interview for a magazine and that’s where I’ll pitch him, right after that interview. And that’s what I did. It worked out, thank God.

So in a way you did a sort of Roger Corman documentary about Roger Corman.

(laughs) Yeah, I guess the approach was definitely a little guerrilla. I mean, we were very guerrilla as far as shooting it. We didn’t have a big budget at all. It was spread over so many years. This meeting that I had with him, the interview for the magazine, was exactly five years ago, about five-and-a-half, actually. I think the production became very real…I got a production company and real financing about three years ago so we’ve been very guerrilla.

Even when I went to go visit him on the set of Dinoshark, I had a crew for one week and then I ran out of money before the dinoshark had got there, and all the blood and the guts arrived so I had to end up staying for three more weeks and I had to stay by myself. So I ended up shooting, doing sound, everything, alone, since I couldn’t keep anyone there. I actually shared a room with a PA from that set because I couldn’t even afford to stay [in] a hotel room. Roger said, “I’ll help you out there but you have to kind of help me out. I need you to assist with filming sound for second unit.” So there was this laundry list of things that I entangled with on his production. I was recording sound for second unit and first unit, sometimes. I became the DP for second unit and was an extra in three different scenes in the movie. And I was shooting visual effects plates quite a lot as I was trying to film my own documentary at the same time.

It also works in terms of the way he works. What’s so wonderful about the documentary is seeing how slowly he can sort of bring people along and make them do these outlandish jobs just to get their dream going. So you’ve become a part of that.

Yeah. It was really funny because I had read so many books and watched so many behind-the-scenes DVD extras, interviews with people, and by this point I was interviewing people and everyone had these horror stories of grueling shoots…but they’re kind of awesome at the same time. You’re in this DIY film making school and you don’t even realize it. It was a treat, because I didn’t go to film school, the movie really became my film school. Doing my thesis film was kind of like being on the set of Dinoshark, and really understanding the mechanics of how a Roger Corman set is operated. It’s really true. And at that time, Roger was, I believe, 84 years old, and I’m on the set of this 84-year-old man’s movie and it’s exactly the same as it was, probably, when he was 34, like 50 years later.

You mentioned that you were already interviewing people at that point. How reticent were people to come aboard and talk about the man that gave them their start in the industry?

I was really lucky, because most people — pretty much everyone — wanted to go on camera once we did the heavy lifting of just getting the request in front of them. Most everyone agreed to do it and wanted to speak about Roger because they know that he’s not a household name, not really known outside hardcore film fan[s].

I think people wanted to spread and share these stories to kind of secure his legacy and to pass it down to a whole new generation of aspiring film makers that should know who Roger Corman is, to understand his philosophy of how he makes movies. I was really lucky in that regard. What was very painful, and where our patience was tested, was just getting in touch with these people…it was really crazy. And like I said, Roger wanted nothing to do with it, [and] I wanted to keep that clean division as well.

My producers were really great. We had so many different angles to try and get to these guys. It’s like, “oh, your friend cuts so-and-so’s hair? Ok, give them a request!” We were trying everything to go through anyone we knew that knew anyone of these guys, not just relying on PR people and agents to get their clients to come out, for free, to talk about someone. It took years, it took years.

The big piece of the puzzle was when Polly Platt came on board as a producer on [this] film. She really legitimized the project, I think, to this community of people. She personally wrote to every single person that I interviewed and I think people felt a little bit more [like] this was an authentic, legitimate project. Eventually there was this kind of thing in the air that everyone was talking about it and felt like, oh, if you don’t participate, this is like the end-all, be-all documentary about Roger so get in there. Then it became easier.

I do a lot of work during the interviews to try and not…I don’t want to say prove myself, but I guess it was proving myself to people like [Martin] Scorsese. Not just so that they would give me really good interviews, and open up to me on camera, and give me time, because with all these guys it’s like, “you’re getting ten minutes, that’s it.” And I’m constantly fighting to turn that ten minutes into two hours. The other big part was getting them to enjoy the experience so that they would go and say good things to the next person in line. It was a lot of work.

And [with] Jack, for example, that took years to get his interview. A lot of times people would say yes and it would take a year, like Jonathan Demme. He said yes and it took exactly one year before I was actually sitting in a car with him, interviewing him, because guys are crazy busy and they’re all over the world and their schedules are insane.

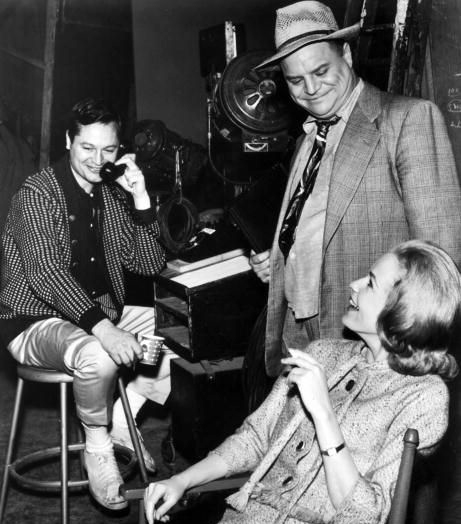

From a directorial standpoint, what I enjoyed the most was having these talking head interviews but…with like the Demme interview, you’re just in a car. It did lend itself to that hand-crafted Corman idea as well. Was that something that you went into planning to have talking heads with dogs running around or that just sort of happened in the moment that you were later able to use so well?

Definitely an intent. The style I was going for was to get as much energy as I could out of the talking head situation. It was a combination of the technical situation that most of these guys are really busy. When I would get a call from someone’s assistant, “oh, Bruce is going to get his hair cut later this week. Maybe I could squeeze you in there!” And I [was] all for it. I’m there, it’s done, it’s a deal.

I liked that. I liked filming people as they were in route to other places or doing other things because it kind of broke the wall down. What I did not want to get myself in to with this movie was I knew I was going to interview a lot of celebrities and I didn’t want to put them on a film stage [cheap plug?] in a director’s chair with this heavy lit glossy lens kind of a look. I wanted it to feel kind of rough and tumble.

I wanted the audience to hear these stories coming from people like Ron Howard, walking around his neighborhood. It’s just a white picket fence neighborhood in Connecticut. It’s nothing super glamerous. We just walked to the cemetery and just kept chatting. Also, Ron Howard is talking about a period in his life where he was really trying to cut his teeth as a director and I thought the storytelling would be that much more real if the locations and their environments felt real and unlit, more down to earth.

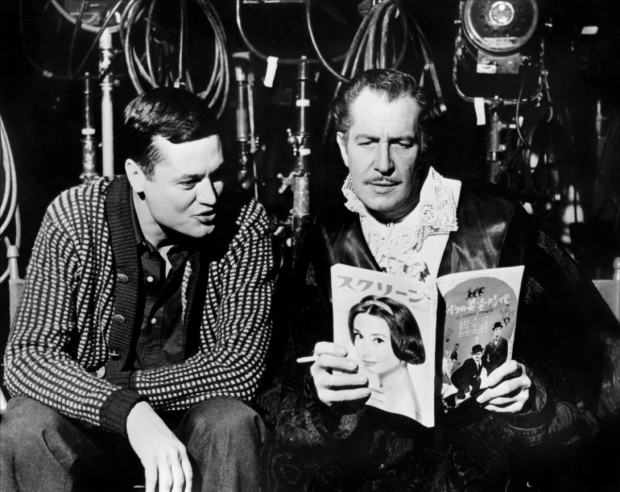

Jack Nicholson, for example, is a kind of larger than life personality. I wanted it to feel like the audience was sitting at the end of the couch, talking to him like I was. So I often encouraged everyone to not get dressed up, this isn’t fancy. Jack was in his flippers, a white t-shirt and khakis, y’know what I mean?

And there was no lighting. We didn’t light anyone. We used all available, natural light because I just wanted it to feel authentic.

If the film is about Roger Corman, it probably stars Jack Nicholson. The interview bits you have with him are phenomenal and hilarious and moving. I couldn’t believe the range that he gave in a normal documentary interview. For you, as a first timer, how daunting was it to get that sort of truth out of so many Hollywood luminaries?

Well, sometimes I think it was just [being in] the right place at the right time. With Jack’s interview specifically, it was an all-day affair, it was the longest interview I had, so that helps when you’re interviewing someone. The more time you get, the better. With him, I think it was a special case [where] he never goes on camera. He’s done it one other time for a documentary on Stanley Kubrick [A Life In Pictures]. I think he’s done a couple of appearances for some DVD extras of movies he’s directed. But as far as participating in a documentary, there has been only one other instance.

I think that because it’s so rare for him to be on camera as Jack, versus the character “Jack Nicholson,” he just had all this bottled up stuff that he wanted to share. And we were also talking about a time period in his life that was twelve years leading up to Easy Rider. I think most people are only interested in his career post-Easy Rider. We were kind of re-hashing and exploring through a time period that maybe even he doesn’t think about that much. It became an emotional journey for him and at a certain point, I was just there with the camera and I think the camera started to turn in to Roger and I think Jack was just letting it come out and talking to the camera as if he was really communicating to Roger all of these things that he’s probably never told him to his face.

My favorite moment, besides when he kind of gets very emotional towards the end, is when he says, “Roger, if you had ever paid me over scale, you would’ve had Easy Rider.” And he was doing all that to the camera so I feel like I probably had little to do with it (laughs). And that’s how it was with a lot of the other interviews, with David Carradine, with [Peter] Bogdanovich, a lot of them became very emotional and there was a lot of sentiment in their interviews because they were all just thinking about a period in their lives when they wanted either to crossover as something else or they needed someone to believe in them, they needed someone to take stock in their dreams, and Roger was the guy who did it.

There was also the fun parts of the interview when they were thinking of all the crazy things that Roger had them doing for, like, no money, you know what I mean? And those stories were hilarious so we had a good time.

It feels almost like we’re watching a high school reunion of sorts, where all these people are going back and experiencing everything again.

Yeah, and it felt like that even in the interviews, too. As I would kind of drift from person to person, after every interview, each person would go, “oh, who are you doing next?” And I would say, “oh, this person, this person, and this person.” “Oh! Tell Ron Howard I said hi and tell him that I still owe him a cheeseburger from that bet we made on the set of Eat My Dust!” So I was constantly passing messages back and forth between these guys. They are never together as a unit, so what was really special about this movie, even bigger than Roger’s story, it kind of put together this whole school of people who were trained to make movies in this very specific way. It kind of brought them together under this one umbrella in the film.

You look at the breadth and amount of films that Roger Corman’s made. Can you talk a bit how you think a man with 400 films to his name can be so obscure?

First of all, I think we don’t know Roger because it’s never been a priority to him to have his name out there. I think for a lot of people in the film industry, they kind of become a brand, they brand themselves as actors, as directors, as writers, producers, whatever. And Roger, that just was never something he was interested in doing. He organically became a brand because he was just so prolific that you can’t help but pay attention to a man who’s made over 500 movies for six decades and is still working.

It was definitely a challenge. Jack said something that was very, very, very on point that if he hadn’t had made all of these other kinds of movies…it would be totally different if he had only made the Poe pictures. Or if Roger Corman only did the movies up until ’59, which is like the black-and-white, science-fiction-y comedy horror films. But he just kept going on and on. It’s just fascinating, because he’s responsible for so many different types of movies. The motorcycle movies, the women in prison films, the kind of woman butt-kicker movies (that I like to call them) starting from Apache Woman where women are these female protagonists, pre-Angelina Jolie. He authored all these types of films and it was overwhelming at points in our edit to get through it. It took me two years straight as a full-time job just to study all of his movies. I’ve seen every single Roger Corman film, and watched a lot of them over and over and over again. Just to get through his body of work, it took two straight years.

It was crazy to go in there and try and pick which movies we were going to focus on. And there were a lot of movies that ended up on the cutting room floor that I’m very, very, very sad about, but.

Any one specifically you want to mention?

I think the one I’m the most depressed about that is not in the feature — but it will have time in the DVD extras — is X: the Man with the X-Ray Eyes. That’s probably one of my favorite Roger Corman movies and it’s a great film starring Ray Milland, who is one of my favorite actors. It was just a movie that didn’t fit in with the narrative of Roger’s career. The making of the movies ran parallel with where we are in Roger’s journey as a person, and Man with the X-Ray Eyes was just kind of this extra cool story that we just didn’t have time to fit in.

Will there be a DVD release with extras and all the other stuff that didn’t make it into the movie itself?

Will there be a DVD release with extras and all the other stuff that didn’t make it into the movie itself?

Yes. I want to release the mother of all DVD extras (laughs). The first cut of this movie was six hours.

Oh, wow.

Yeah, so there’s a lot. I interviewed over sixty people and they’re all very, very interesting. There’s stories, great stories from, like, Monte Hellman and Jack Nicholson. They had this whole world that they had going on with Roger making the westerns, The Shooting and Ride in the Whirlwind. Monte going on to make a movie called Cockfighter in the ’70s starring Warren Oates. Monte has this whole world with Roger that I want to explore.

The most moving story that I can’t wait to include and to share with people for the DVD is that of Floyd Crosby, who was a cinematographer who shot about 80%-90% of Roger’s earlier films from the ’50s and ’60s. Floyd Crosby received the first ever Oscar for cinematography for Tabu: A Story of the South Seas. He was a great DP and he couldn’t get work by the 1950s because he was blacklisted as a communist, all because he had European, liberal friends. Roger saw that he wasn’t working and called him up and asked, “do you want to come make these low-budget science-fiction movies?” (laughs) And that’s why the movies kind of looked good, because he had an award-winning DP shooting his movies. That’s just so Roger Corman, to be that resourceful, y’know?

Unfortunately Floyd Crosby has passed away, but his son is actually David Crosby, the musician, and we sat down with him and had a wonderful, awesome interview with David and it’s very emotional, because David felt that Roger basically put food on the table. Roger employed his father when no one else would and David was extremely grateful to Roger for that. And that’s a big story that I can’t wait to eventually share with people.

Going from six hours to just over ninety minutes, what was that process like?

It was insane. It took over a year to do. I’d say I was probably in post for two years on the movie. It was hard, you know? The hardest part was editing. But I’m happy with where we are with the film now. There’s no way to just include every story so I guess that’s what these DVD extras will do.

The film feels more like an appreciation than a real study of the man, especially the parts in the ’80s and ’90s where he went through some bad times. Was that something that you thought of going into it? Was it just the running time that made it more of an appreciation than anything else?

The film feels more like an appreciation than a real study of the man, especially the parts in the ’80s and ’90s where he went through some bad times. Was that something that you thought of going into it? Was it just the running time that made it more of an appreciation than anything else?

That was something in the six hour cut. I had his whole career, post-Star Wars and Jaws, going into the “Lumber Yard” years. He had a studio in Venice [CA] where he was turning out these low-budget horror films like Chopping Mall which is one of my favorite movies of all time. Just kind of more gory horror films in the ’80s and ’90s.

I had that in the six hour cut, but I had to [lose] it. There was not enough time. And there was a whole new generation of film makers who came from that school, people like Catherine Hardwicke, Bill Paxton, James Cameron, and Gale Anne Hurd were kind of on the cusp of the beginning of the “Lumber Yard” years. I just didn’t have time to keep going and going.

What ended up happening was that the film ended up becoming something different over the course of shooting. Roger got the Lifetime Achievement award [from the Academy of Arts and Sciences] about halfway in to the movie, about three years in. It changed the ending, because all of a sudden I went from this movie where I [could] put more chronology in there and go longer, through the years, because I already had this big ending. Here’s this guy who’s done all this stuff and you don’t know who he is! and you should recognize him and the Academy should give him praise! …And then that happened, so the thesis of my film got proved with him winning the biggest honor you could possibly get.

The other thing that happened was that I was really shocked and surprised when I sat down with people. [They] got really emotional. They had fun with me for an hour and then they would say something [very] real. “Look, we can sit here and we can laugh and have play time, thinking about the craziness of the sets, but I really need you to understand how much this man affected my life, how much this man affected me as a human being, how much confidence this man gave me when no one else would.” It really hit home with Jack’s interview.

All of a sudden I was looking at my footage and I’m like, “this is where we have to end up at the end of this movie. We need to arc here, we need to put the movies down and look at who the man is and look at the kind of human story that’s here, not just the movies.” That was the reason why I cut the chronology around basically the late ’70s with the studios kind of adopting Roger’s formula. Also, that’s where we still are today. We’re probably going to go through a new cycle very soon, but right now we’re still kind of in that blockbuster era. There’s no real indie scene because the studios are very powerful and indies don’t get played in theaters nowadays; people aren’t going to them in droves. That kind of started in the mid-to-late ’70s and that’s where we are today.

And Dinoshark, I thought putting that verité-style story in there presented Roger’s career post-Star Wars and Jaws, which was a career where he was making movies but they’re not going to theaters. It killed him in that way. Now all of his movies were going to home video and they’re on cable.

It seems like there are three love stories balanced in your film. There’s clearly Roger and film making itself, Roger with his wife who he met through film making, and then all of these people who have grown such adoration for him over time. It’s a weirdly complex movie considering it’s about one man and what he’s done.

I also wanted people to understand [that] if you do know about Roger, what you usually know about him is that he’s this really cheap man, this penny-pinching producer who’s just trying to churn out movies to make a dollar. I kind of wanted to investigate that myth, shall we say. And I realized that yes, he’s prolific, but he just can’t help himself.

The Terror is a perfect example. He just can’t let a set be up for more than one day without someone taking advantage of it. It doesn’t even have to be him. it’s just a waste [to him]. It’s just this tick that he has where he’s just always trying to figure out how to make something from nothing. It’s not driven by money. His obsession with money is because that affords him [the opportunity] that if he keeps his cost down, he stays in business. That’s what’s more important. And what you end up seeing in the movie is how he has this obsession and this love for cinema. While he’s kind of focused on that, these other people are kind of chasing after him to get to know him.

I think Julie [Corman, his wife] and he have a very interesting relationship in that way. I love the story when she’s talking about when he proposes to her and goes off to the Philapines and doesn’t call her for a few weeks. He doesn’t call her because he doesn’t want to waste money on a long distance phone call. Meanwhile, she’s trying to figure out when they’re getting married. That’s how their relationship is, it’s hilarious. She’s a woman that is secure with herself and their relationship where she can laugh it off and she knows that it’s just a part of that Roger Corman tic.

Do you think that with the honorary Lifetime Achievement Oscar it might afford Roger some more opportunities back in theaters?

That’s a really good question, and I don’t know. I don’t know if that’s even really a goal of his any more. He’s moved on to the new thing, which is the internet, and the web. What’s so great about the guy is that he’s always kind of looking at the new means of distribution. In the ’50s he saw drive-ins as the new wave, and also the hard-top theaters, that were turning out “grindhouse” kind of movies. Then in the ’80s he saw the value of home video. And then cable and on demand. He’s always the trailblazer with the new method of distribution, and right now it’s the internet. He’s making movies for the web. He just did a huge thing with Netflix, him and Joe Dante and Julie made a film called Splatter where you can choose your own ending. He’s still doing things with the SyFy channel, for cable. But I think he’s probably going to challenge himself to become a master within new things. I think he understands that the theater experience is kind of a dinosaur, in a way, and it’s definitely not where you go as an independent theater.

The man doesn’t stop.

He doesn’t stop. He doesn’t stop. It’s not an option.

Is there anything up next in the docket for you?

This year, I also made another movie called, Outside In which is a look at the MOCA [Museum of Contemporary Art] exhibit here in LA of the history of street art and graffiti. I made it fast and furiously, five months versus five years. I’m now developing a documentary television series out of it that will kind of be along the lines of a Ken Burns‘ look at the history of street art and graffiti from around the world, starting in New York and the affect it’s had and the phenomenon it’s become today. I’m really excited about that.

And I’m also crossing over and doing my first feature as a narrative film director and it’s very, very Roger Corman. It’s an intergalactic love story, a science-fiction picture that I’m really, really excited to do and it’s kind of pulling a lot of my favorite things from a lot of different Roger Corman movies and making it a really fun, low-budget science-fiction picture.

So are you going to say right here that you’re going to unveil who Banksy is in your TV series?

(laughs) He might already be in my movie! Who knows?

Roger Corman: The Exploits of a Hollywood Rebel opens this week in NY and LA. Get showtimes and further information here.