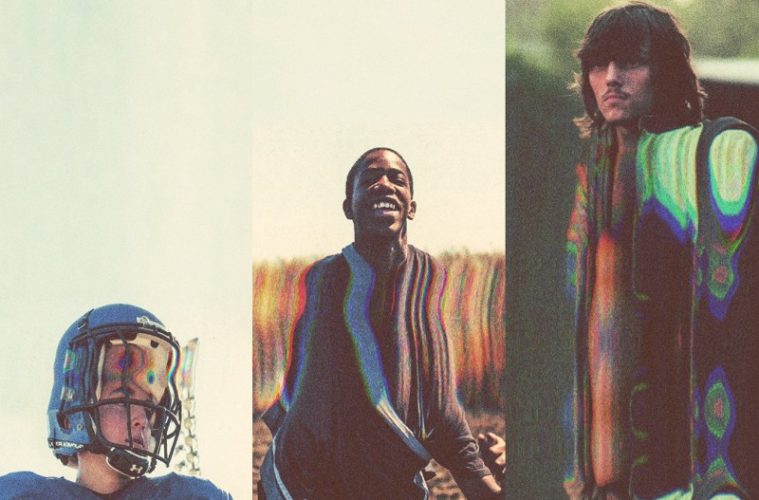

It would be easy to dismiss Nick Reyes, Larry Young, and Tyler Carpenter as three variations on the same thing: poor American youth. The simple fact their stories are combined within Daniel Patrick Carbone’s poetic look at nature, nurture, opportunity, and struggle in rural areas of our country entitled Phantom Cowboys makes the case. But anyone who watches these parallel journeys will reveal this thought’s error. You’ll see how role models can improve one’s outlook on the future. You’ll see how the stigma placed upon us because of the color of our skin or the city of our birth can dictate fate’s path. These boys might be shown rejecting choices that would have objectively bettered their situation, but in their eyes those possibilities were never real.

This is our nation’s true tragedy. We live in a self-proclaimed “land of opportunity” that forgets the asterisk denoting myriad stipulations to see the dream through. Listen to seventeen-year old Nick speak about wanting to leave the wasteland of his hometown of Trona, California before fast-forwarding six or seven years to learn about his homesickness, refocused goals, and new outlook towards life’s many gifts that youth often ignores. Watch a teenage Tyler Carpenter grow older despite seeming like a virtual carbon copy of his former self save one hugely impactful difference: fatherhood. He shifts his priorities, reflects on his luck, and acknowledges personal success will always pale in comparison to his daughters. And witness Larry’s infinite hope fall prey to circumstances our faulty society projects upon him.

Carbone presents their forward trajectories as being forever linked to their pasts. While we meet them all young with a quick transition almost a decade later to see the surface differences, he subsequently moves back and forth between them as though they are in a perpetual conversation with each other. An adult Nick watches the homecoming game, reminiscing with an ex-teammate about missing the pressure while his fresh-faced teen reappears within the pomp and circumstance of his own experience of that same tradition. Larry, just out of prison, sees how everyone has grown and acknowledges how it’s up to him to be a positive influence on his little brother — to ensure his own ear-to-ear grin at thirteen never disappears like his might. Cause meets effect; fantasy meets reality.

And while the depiction of their separate lives fluidly moves back and forth, so too does the film. Carbone wields a common theme of aridity as though Nick, Larry, and Tyler’s worlds within California, Florida, and West Virginia respectively are about to become the desolate ghost towns many throughout the country already assume. The dirt of Nick’s football field kicks up into dust like the racetrack Tyler zooms around. That dust blankets our view, blocking our vision before becoming the hazy smoke of Larry’s family’s sugarcane fields burned at season’s end. These kids are literally exiting a curtain of opaque hindrance; the possibilities on the other side endlessly optimistic yet psychologically out of reach. Where they land isn’t always bad, but it’s also never where they predicted.

It’s this realization that makes their stories so relatable regardless of your own upbringing. You don’t have to be the son of a dirt road racer, the product of hard work always tempted by the easier shortcut of criminality, or a blue collar kid dreaming of greatness resigned to accepting and enjoying the life he refused to believe would be his to understand the conflicted feelings onscreen. We’ve all evolved through that transition between adolescence and adulthood. We’ve all found our priorities shift and our desires rebuilt. Some of us need maturity to appreciate what it was our parents did for us and what we could in turn do for our own kids. Some need a wake-up call and others an excuse to let selfish ego wash away.

These men experience death and poverty right alongside life and success. As Tyler relates: just because you aren’t rich doesn’t mean you aren’t okay. Maybe like Nick you’ve saved your money for an expensive car — not to show off, but to remind yourself what you can accomplish despite so many challenges begging you to fail. Or perhaps your life mirrors Larry’s wherein you can never outrun the future others assume is unavoidable. But even as the latter faces the consequences of his actions, he doesn’t give up. It might just be a show for the camera, but looking into his eyes makes us believe he still possesses hope. Maybe he just needs a job like Nick or a family of his own like Tyler to see it realized.

America has immense flaws that stack the odds against those unlucky enough to be born without a head start, but it also affords the room to excel beyond them. Will Nick, Larry, or Tyler be millionaires in ten years? Does it matter? That’s not the point of Phantom Cowboys and neither is showing an invisible faction of the population with nowhere to go. The point is instead to highlight how we’re forever changing. How wishes can transform into prosperity without money, celebrity, or education. Carbone’s film portrays love — of family, friends, places, and things. It comes in all shapes and sizes, each as potent as the next. Because our lives aren’t set in stone, joy proves as feasible as pain. As long as we’re alive, though, there’s promise.

Caution: The film features graphic scenes of rabbit hunting and skinning.

Phantom Cowboys is now playing the Tribeca Film Festival.