Perhaps the lessons in history class have changed in the era of transparency, however, the 1971 burglary of an FBI field office in Media, PA seems to have been relegated to a footnote to the larger history of political protest. Told in recreations and talking heads, Johanna Hamilton’s documentary 1971, which had premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival and will be screening at DOXA, reveals information rarely known now that the statue of limitations has expired along with the release of Betty Medsger’s book The Burglary: The Discovery of J. Edgar Hoover’s Secret FBI.

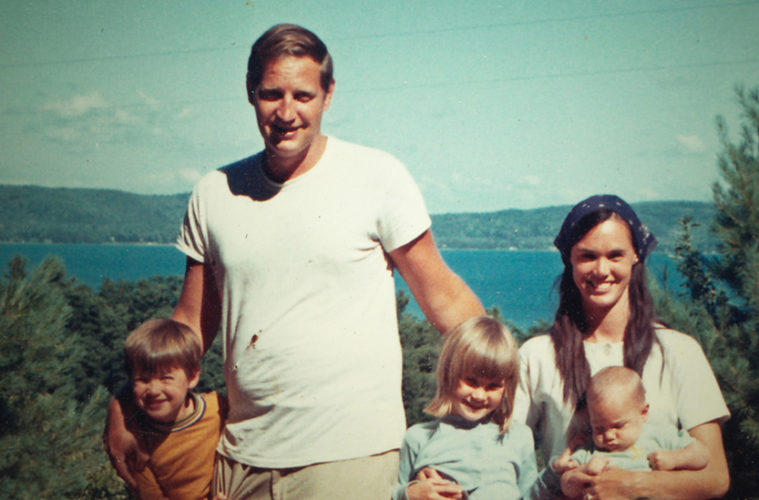

The film tells the story of ordinary men and women, socially conscious parents living in Philadelphia, who infiltrate a suburban field office in a non-descript apartment complex. The burglary and subsequent release of documents threatens the field office structure; here, sensitive and controversial documents were guarded behind a few simple keyed doors with no building security. Bonnie Raines, who appears younger, is sent in to case the join, posing a college student working on a paper about females FBI.

The group, known as the Citizen’s Commission to Investigate the FBI, attacks on March 11th, a night when much of the country is distracted with the Frasier-Ali fight at Madison Square Garden. The members, including Keith Forsyth, John C. Raines, Bonnie Rains and Robert Williamson, removed subsequently all of the files in the field office that evening; Edward Snowden and his flash drive, comparatively, had a much easier time.

Like Snowden or even the current Bridgegate fiasco in New Jersey, secrets are revealed once the documents are disseminated to the press who continue to ask questions. Quite literarily reading between the lines of redacted papers, the most disturbing revelation is revealed: COINTELPRO, a covert program to infiltrate domestic political organizations that’s not at all unlike the FBI’s (and NYPD’s) monitoring that currently exists and is documented in another stunning Tribeca documentary, The Newburgh Sting.

The New York Times, LA Times and Washington Post receive the physical, primary source documents anonymously from the Philadelphia-based group. Both Times return the documents while the Washington Post’s Medsger continues to dig along with Carl Stern of NBC. Stern is the one who, via a FOIA request, breaks the COINTELPRO story.

Well-told and engaging, 1971 effectively build a portrait of the times and what follows without leaning too heavily on the recreations. What is shocking, perhaps, is how little has changed since then. The film’s marketing aptly references Snowden and Julian Assange, including the attempts to find the members. (Of the eight members, only one was ever an FBI suspect.) 1971 is a frequently fascinating history lesson, and perhaps what’s so troubling is that the overreach continues. Smartly, the documentary avoids drawing too many connections that raise the alarm of paranoia.

1971 premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival and is screening at DOXA. One can