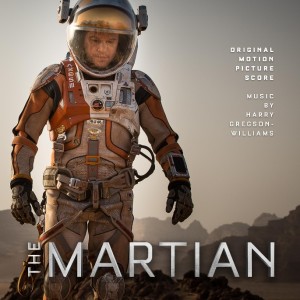

After crafting the scores for Blackhat, The Town, Kingdom of Heaven, The East, and more, composer Harry Gregson-Williams reteamed with Ridley Scott for The Martian, the film adaptation of Andy Weir‘s best-selling novel. It tells the story of Astronaut Mark Watney (played brilliantly and charismatically by Matt Damon — check out our review here) as he struggles to get off the Red Planet.

We had the chance to recently speak with him about his work and the composer was quite happy with the score and eager to hear of our fondness for both the film and the music. In his words, jokingly of course, if you were to like some of the films to which he provided music, you may be in the minority. This time however, we’re willing to bet that nearly everyone on the planet will be in the majority and love The Martian.

We truly enjoyed catching up with Harry, so we hope you enjoy the highlights of our session with him.

The Film Stage: Great to be speaking with you again Harry. I hate to throw praise around that calls something “the best,” but in this case, I really mean it. I’ve long been a fan of yours and Ridley’s work, but I believe that The Martian is the finest score of your career and Ridley’s best picture to date.

Harry Gregson-Williams: It was a thrill collaborating with Ridley because he’s one of the top  directors working. I should be so lucky to be able to say that. I mean, who do we have? Scorsese, Cameron, Spielberg, and Ridley Scott. I’m a lucky devil for having come into contact with him and, as you know, the reason I began working with him is because of having worked with his brother for years and years and years. Back in 2005, Ridley booked me to do a score you and I are both fond of – Kingdom of Heaven. I know not every mortal liked or even saw it, but I can tell you as someone who got very close to it, I loved it.

directors working. I should be so lucky to be able to say that. I mean, who do we have? Scorsese, Cameron, Spielberg, and Ridley Scott. I’m a lucky devil for having come into contact with him and, as you know, the reason I began working with him is because of having worked with his brother for years and years and years. Back in 2005, Ridley booked me to do a score you and I are both fond of – Kingdom of Heaven. I know not every mortal liked or even saw it, but I can tell you as someone who got very close to it, I loved it.

One of the reasons is because of the way it looked and the way he shot it; it was so pristine and beautiful. I’m a great admirer of cinematography and the way things are cut because, as a composer, you spend a lot of time analyzing and studying a film. You really get to know it and get under the skin of it. When something is as tightly written as The Martian, and really well-played by the actors, you notice it. It actually becomes more of a challenge, because you want to do right by such great material, but it’s more of a pleasure while you’re working.

I think the film is a breath of fresh air because it’s unlike anything Ridley has ever done which must have given you great creative liberties. It seemed experimental, and allowed you to touch new ground. So what did Ridley want from you, what did you bring to him, and how did your ideas match?

Ridley is a great director because he leads from the front and does not leave you guessing. However he did not spell out, not in musical terms, where he wanted me to go. He made some suggestions of where I might start, and it was more along the lines of what I was thinking. But the great thing about Ridley is that he knows what he wants from his film. So if I were to write something that was a shade too dark, or let’s say too active, he would jump on that, and the terminology he would use is not too different from an artist or painter.

He talks in terms of tone, shade, color, light and dark – we share a terminology between art and music. For instance, one of the first ports of call was to discover what character the planet Mars was going to play. What was this bringer of war? Was there something wholly malevolent about it? And we discovered, quite early on, that we didn’t need a real darkness to Mars because that was counterproductive, and not quite accurate. It’s quite clear from Watney’s travails that if he puts a foot wrong it’ll kill him in an instant.

While Mars needs to be treated with care, the majesty and mystery of the planet are words that Ridley threw out to me. I responded to that, so instead of making Mars a monster or a bad guy, we tried to make it more mysterious and more awesome. Not to say that we didn’t make it austere in places, and certainly threatening, but those are the kind of adjectives he used to get me started.

The hope is that someone will write something, and the director or producer will come into the studio and go, “Great, thumbs up, next!” But that rarely happens, like a hole-in-one in golf. If you go through life expecting that to happen, you’re not going to last long as a film composer. It is a team sport after all, and very collaborative, especially with someone like Ridley. He has in mind what he wants from a scene, not necessarily musically, but what he wants you to bring to a scene.

He’ll offer suggestions of what I might do, or maybe what I shouldn’t be doing. Early on in the film, Watney is trying to make water and Ridley tells me “I like the way things are bubbling along underneath, but there’s a hint of darkness to what you’re doing and I don’t see why we should be doing that. Watney is such an optimistic and humorous kind of guy. He loves his science, is a bit of a tech head, so let’s make it a little bit more fun. Don’t be so serious. Not to say comedic, but not so many brush strokes of darkness.” So I altered what I had by a couple degrees to meet him at that place, and that’s how film scores are born really.

I like what you said about not painting Mars too dark, and I think one of the things I took away from it was that Watney’s there by himself yet it’s an epic, two and a half year struggle for him to get home. It’s incredibly dangerous, yes, but it’s also incredibly simple – it’s him, and his tools, and his talents. I think what I picked up on is your two note motif which is used in tracks like “Mars” very subtly, in “Emergency Launch” which is dramatic, and in something like “Pathfinder” is kind of spacey.

Absolutely. I’m glad you picked up on that, because that two note motif develops into a full blown theme as the film goes on, and it’s not a coincidence that those notes rise. One talks of positivity, and staying optimistic because that’s Watney’s character; he’s not going to lay down and give in. Very early on, when he’s on Mars he says to himself “I’m not going to die here.” That was the determination of this guy, so these were the seeds of determination I was able to sow very early on, and it didn’t seem like he earned the right for this to be symphonic.

As you said, this is a very simple story at its heart. It’s a very personal story about one man’s survival as well and we are helping glorify as well as enjoy his scientific abilities. So the music is quite small, not overplayed to begin with, and it grows as he grows in stature and gets closer to being rescued.

To use the analogy of a kid in a sandbox, well Watney is a big kid in a very big sandbox!

Absolutely! [Laughs] It also helps when the writing is so tight. Drew Goddard did an amazing job interpreting Andy Weir‘s book which is a great read from cover to cover. I went back and had a look at the book the other day and it’s quite astonishing what Drew did. Seeing the film, you think it couldn’t have been done any other way, but in the book, Watney is thinking a lot of these things, not talking to a camera.

So I thought that was a really smart and quite current aspect to the story. But I think a lot of it can be traced back to the way Drew Goddard painted this picture and how Matt Damon interpreted it. I thought you did such a fine job.

I think that the film solely rested on Damon’s shoulders, and it seemed like a vehicle just for him. But like you were saying, those internal thoughts where put into exposition for us each time Damon talked to the camera. It really made us part of the story as opposed to something like Cast Away or All Is Lost.

True. Then there are the intercuts of everyone on Earth, and so their theme is something much warmer and something that will come together towards the end of the film. I loved the casting as well. I thought it was surprising and successful because of the smaller parts. Mackenzie Davis, for instance, happens to steal every scene she’s in. With a small part, were you to read the lines on the page, you might not think it’s remarkable. But what she did with it was great, and how Ridley shot it resulted in another great element of the film.

Benedict Wong is another one. I love that line, “Thanks to my uncle in China, we’re going to get another shot at this.”

[Laughs] You know, I remember telling Tony Scott that I loved his casting in Spy Game. In particular, there’s an actor who plays a small part but it’s quite pivotal – he’s always stuffing his face with Chinese food, eating it out of a box which is what Tony used to do. And I love the casting of that, so yes, Benedict Wong put me in mind of one of these characters that on the page perhaps doesn’t read particularly humorous, but the way he delivered it was really quite cool I thought.

What’s great about the film is that there are a lot of peaks and troughs, but it doesn’t spend a lot of time on the downers. There’s a lot of positivity and hope flying around, and that’s something I had to underpin with the music which was enhancing Watney’s emotional arc throughout the film.

You had to cover a large range of emotions, but not only that, it seems like you had a lot of different tools in your palette. The score had more strings than I would have expected in a so-called “space” film, but “Hexadecimals” has a very Brian Eno, almost planetarium vibe to it, but then “Work the Problem” sounded like there was a didgeridoo in there. How did a varied palette help convey those emotions?

Getting the sonic spectrum together for a movie like this was very important. It took a lot of time before I even began writing music because I needed to find what sort of instrumentation would work. It seemed to myself and Ridley that a hybrid of synthesized and fully orchestrated music with some choir would work. But we would just have to pick our spots. One of the things I decided early on was to not use choir too often. When I did, I was careful and I wanted it to be like a Greek chorus – it almost represents mankind back on Earth wishing this guy well and hoping the best for him.

Getting the sonic spectrum together for a movie like this was very important. It took a lot of time before I even began writing music because I needed to find what sort of instrumentation would work. It seemed to myself and Ridley that a hybrid of synthesized and fully orchestrated music with some choir would work. But we would just have to pick our spots. One of the things I decided early on was to not use choir too often. When I did, I was careful and I wanted it to be like a Greek chorus – it almost represents mankind back on Earth wishing this guy well and hoping the best for him.

I had to find a text that would be suitable for the choir to be singing. What I found working on Kingdom of Heaven was that choirs sing well in Latin. A lot of Latin text has these religious overtones, so I went to a Roman philosopher, pre-Christ, who had written about the infinity of space and the larger question of who we are and where we stand in the universe. I was able to give the choir these moments in the score that blended in with the orchestra as they represented the goodwill of mankind concerned with Watney’s plight.

I imagine that’s got to be the fun part of the job – doing that research, even if no one in the theater will have any idea the thought that went into it. It just sounds cool. I talked to Steven Price about Fury (read our interview here) and he gave the choir very specific Germanic Bible verses to sing for those haunting WWII tank battles.

I know that it’s fairly subliminal, but these type of things make all the difference. We wanted to make sure that none of the music sounded necessarily holy, but there’s no reason why it couldn’t be quite spiritual, if that makes sense. There is a distinct difference between the two and in a scene where Watney’s crops were wiped out, we used just one voice to enhance the scene.

I was in a similar situation with the first Narnia movie that I scored. I wanted to use some choral work, but I didn’t want them singing ohhs and ahhs, I can’t stand that. [Laughs] They were singing things from an actual Runic text, which is so ancient of course no one could possibly understand or get that if they heard it. But it at least gave the choir some point of view and something to really sing about.

Another new element in this which is lacking in past Ridley Scott films, aside from the humor, is the number of source music tracks. I know that composers don’t usually have anything to do with song placement, but how did you approach writing music when you had to work between so many sequences where Watney is listening to a song?

When I came to the film, quite early on, Ridley was already four weeks into his cut of the film – they were well into post-production. Most of the spots that you see now were already covered with a song, and actually it was already identified in the script. A joke of the film is that Watney was stranded on a planet with a bunch of music that he didn’t particularly like, but he grew to like it because he didn’t have any other choice. There is nothing else to listen to.

In the script, it didn’t specify that “this is a Donna Summer song and this is a David Bowie song.” But what was fascinating is that editor Pietro Scalia had some really good suggestions. We tested the film with two David Bowie songs, and we ended up with one, and the spot where we took it out actually became the biggest moment in the score.

Once Ridley decided he did not want to song there all eyes were on me to provide music because it’s a sequence without any dialogue. It’s when Watney leaves the relative safety of his HAB and crosses Mars. That was the cue called “Crossing Mars” which was a big moment for the score. It is played out in a different emotional way than had there been a song. But these are the choices that the director makes, and my job is to provide an option, and once I had written the piece for that I felt strongly it was the right thing and he did as soon as he heard it.

Last time we spoke was in 2013, and we discussed the work you did with Halli Cauthery on The East. At that time you had just had your fourth child. My wife and I just had our first child in April. You now have five kids, so while I have my hands full with one, how do you find the balance between your family and the demands of scoring Hollywood films?

Last time we spoke was in 2013, and we discussed the work you did with Halli Cauthery on The East. At that time you had just had your fourth child. My wife and I just had our first child in April. You now have five kids, so while I have my hands full with one, how do you find the balance between your family and the demands of scoring Hollywood films?

I have very much changed my mode of operation really. Back in my busiest decade scoring films, between 2000 and 2010, I had a large studio space which I rented on Venice Beach. I had a lot of people working with in my building and it was growing. At the end of that time, around about 2013 when The East came along, I didn’t score the whole of The East because I decided to take a sabbatical.

I stopped scoring films because I wanted to do something else I valued which was teaching. That’s what I came from before – I taught music and sports in schools. So I thought a good way to recharge my batteries was to unleash myself from that rolling stone that was my studio. I took a year away and did not take on any films during that period. After a year, the first film I came back to was The Equalizer. When I came back, I felt renewed and energized.

Now I have my studio in the back of my house. I built a studio in my garden, so the balance between family and work now is much more healthy I think, and is the way I like it. Post-production for The Martian was not in L.A., it was in Europe, and fortunately I got to write the score in my studio at my home but then take off and record the music at Abbey Road which is a great pleasure, as always. [Laughs]

Well that’s better than taking your entire shop and moving it to London to score Kingdom of Heaven, right?

Those were really exciting times, and I would do the whole thing again if I were asked. The difference though being Kingdom of Heaven was the first time I’d worked with Rid and he needed his composer to be on hand. He didn’t want me to be sending him music, he wanted to meet me face-to-face every week, or two to three times a week for three or four months. So I did the writing over there.

You didn’t score of the whole of Prometheus, or Exodus: Gods and Kings, but you did some outstanding work composing additional music. In cases like those, how was that set of responsibilities established?

I was really glad to be asked, and quite happy to help. While I wasn’t the lead composer, Ridley came to me quite late in the day and asked if I would provide music for those films. Far be it for me to say no, but I had no reason to say no, I was only too pleased to help.

But there’s nothing quite like starting at the beginning and seeing the whole thing through. [Laughs] You would have to ask Ridley his criteria for selecting a composer, but as I came on towards the end of both projects, it wasn’t like he was throwing out other composers’ work, he was just augmenting it. So I don’t have a problem with that, it’s happened to me before. In those instances, it’s me showing up and saying “okay tell me what you’d like me to do, and I’ll do it. In both instances I didn’t come storming in and just trample over what was already there. I was careful to make it homogeneous, and make it feel like it was fitting in with everything else happening in the score.

Well, I ask because I thought the work you did for Prometheus really set the tone of the film. It was extraordinary, and I would have loved to hear more. So now that Ridley is planning not one, but three sequels to Prometheus, has he talked to you about that, or possibly Blade Runner?

I talked to him about Prometheus, but I don’t know anything about Blade Runner. But both things are in the future, and I can’t be certain of anything, so I’m just pleased that he had me do The Martian. We’ll see. If I didn’t screw it up too bad, perhaps he’ll ask me to do Prometheus. [Laughs] All will be revealed next year!

The Martian is now in wide release. Listen to the full score below.