There is no other place where fact and fiction become more indistinguishable from one another than at the cinema. What you see isn’t always what you get: a manufactured image might feel genuine, while an image that feels inauthentic might be the real thing. The finest stories can often be found somewhere in the middle. As Pablo Picasso once said, “Art is not truth. Art is a lie that makes us realize truth.”

Kate Plays Christine, the latest film from Actress and Fake It So Real director Robert Greene, caught a great deal of attention at Sundance — we gave it the highest grade at the festival — and is now in limited release. It’s a documentary that follows actress Kate Lyn Sheil (House of Cards) as she prepares for the role of Christine Chubbuck, a real-life news reporter who committed suicide via handgun on live television in 1974, and the portrayal of whom we see in sequences made especially for the film.

To mark the occasion, we decided to take a look back at some of the finest examples of films that blur the line between fact and fiction. Sometimes dark and sometimes playful, these 17 titles are much more than they may appear from the outside.

The Act of Killing (Joshua Oppenheimer)

The devastating impact of Joshua Oppenheimer‘s The Act of Killing makes for a searing, unforgettable cinematic experience. In 1965, the Indonesian military over-threw their government, allowing small time gangsters, such as Anwar Congo, to rise in society. He was promoted from scalping movie tickets to leading a death squad that helped the military kill more than a million people, many of whom were accused communists. He killed hundreds of innocent people with his own hands, committing gruesome acts of genocide of which most remain unaware. For the film, Congo agreed to stage recreations of the violent acts he committed all those years ago, with full-on Hollywood budgets and special effects. It’s obviously impossible to feel sympathy for a man like this, but, as we meet him, we realize he isn’t looking for sympathy. He is not guilt-ridden or ashamed of his violent past. Quite the contrary. In private, Congo would rather discuss cinema. He loves movies, particularly westerns and gangster films, taking influence from the cinematic violence he saw onscreen, admitting that, through cinema, he learned better ways to kill his victims. In this context, the term “homage” takes on a much darker definition.

Cannibal Holocaust (Ruggero Deodato)

Most notable as the earliest entry in the found-footage genre, Cannibal Holocaust challenges its viewers with shocking imagery, including real violence committed against helpless animals. The fictional acts against its human characters haven’t aged particularly well, despite the bizarre fact that director Ruggero Deodato was brought up on charges of murder in his home country of Italy as a result of the film’s content. (He was later cleared of all charges.) Indeed, the film is still disturbing in its power, thanks to Riz Orlandi‘s haunting score and Deodato’s subversive, if not heavy-handed, satiric execution. You might chuckle at the campy performances, but when that first little animal dies, it impacts like a bolt of lightning. Beyond the surface horrors of real animal cruelty, it’s worth meekly noting in retrospect that Deodato wastes any dramatic potential these shock moments contain, relegating them to mere throwaway gags, albeit repulsively vile ones. I’m not thrilled that such a film exists, but it does, and must be acknowledged for its significance in the history of exploitation cinema. For this and many other reasons, Cannibal Holocaust is one of the worst and most-interesting movies ever made.

Certified Copy and Close-Up (Abbas Kiarostami)

A British writer and a French antiques dealer meet after a lecture, strolling through the sunny streets of Tuscany, discussing the theories in his new book, Certified Copy. The book asserts the irrelevancy of authenticity in art, stating that a copy of a great art work could be considered as valuable as the original. The surface details seem simple enough, but, like any film from Abbas Kiarostami, the surface can be immensely deceiving. As they spend time together, a miraculous change occurs after they are mistaken for a married couple by a kindly local. Caught up in this hypnotic dreamlike narrative, we watch as this man and woman begin to act as if they really are married, a before-unseen back-story appearing before our very eyes. A gripping and mysterious meditation on art, life, and love, Certified Copy is a warmly jocose and beautifully unknowable gem.

The remarkable story of Hossain Sabzian, a struggling Iranian father and cinephile who was jailed for impersonating one of his favorite filmmakers, Mohsen Makhmalbaf, is transformed in Abbas Kiarostami‘s Close-Up from a mournful person-of-interest tale into an uplifting confirmation of the comforting power of art. After reading of Sabzian’s crime in a local magazine, Kiarostami offered the man a chance to recreate the events leading up to his arrest, turning a wannabe filmmaker into the leading man in his own human tragedy. Kiarostami assembled all of the real players from this drama, including the family who Sabzian deceived to re-stage the man’s trial, employing court transcripts, overlooking no small detail in this unbelievable true story. After the trial, the film merges into documentary as Sabzian finally meets Makhmalbaf face-to-face in a moment of heartbreaking elation. Early on, while still behind bars, Sabzian asked Kiarostami to give Makhmalbaf a message for him: “Tell him The Cyclist is a part of me.” After witnessing the fragile sincerity in Sabzian’s eyes, it would be impossible for any true lover of cinema to condemn this poor man. To paraphrase Werner Herzog, another filmmaker on this list who cites Close-Up as one of his favorite films, Hossain Sabzian should always be considered a good little soldier of cinema.

Exit Through The Gift Shop (Banksy)

The notorious film that catapulted Banksy into a household name and forced Thierry “Mr. Brainwash” Guetta onto an unsuspecting art world remains as slyly funny and cryptically obtuse as ever. This densely layered documentary examination of the world of street art focuses on a kooky French cameraman who mutates into an overnight pop sensation, thanks to the carefully worded approval of famed artists such as Shepard Fairey and Banksy himself. At the time of its release, many believed the project to be a playful hoax perpetrated by the elusive Banksy, but, even today, Guetta’s art continues to pop up all over the world. Looking back, Exit Through the Gift Shop feels far less like a hoax than a whimsical indictment of the shallow vapidity of popular art culture, although an admittedly entertainingly scathing one. Note that the first time Mr. Brainwash puts up his own trademark stencil, declaring his creative arrival, he papers over an old tag of Fairey’s Andre the Giant. Out with the old, in with the new.

F for Fake (Orson Welles)

F for Fake, a beautifully manic piece of cinematic eye candy, is a lovely example of Orson Welles at his most mischievous and light on his feet, gleefully shifting back and forth between dueling tales of fraudulent fakery and deceptive hanky-panky. The film is not attempting to trick, but play with us. Dance with us. Welles himself greets us and takes our hand, introducing us to his charming and duplicitous subjects. On the sunny island of Ibiza, we meet Elmyr de Hory, a sophisticated art forger so adept in his technique that his fakes often fool even the original artists. Amongst Elmyr’s various hangers on, we also meet Clifford Irving, a writer who once studied under the flamboyant faker’s skillful tutelage. Later, Irving rose to fame after hoaxing the world with a fraudulent biography of reclusive billionaire Howard Hughes, from which he netted himself nearly three-quarters of a million dollars in a publisher’s advance. F for Fake is an exhilarating and engrossing romp through the gray areas of art and truth, which would make for a perfect double feature with Exit Through the Gift Shop.

Forgotten Silver (Peter Jackson)

A charming mockumentary ode to the untold lost epics of silent cinema, Peter Jackson‘s Forgotten Silver is perhaps most famous for being misinterpreted by its original television audience as real. Looking back, the film is a dryly poker-faced comedy that forgoes the beautifully rambling Christopher Guest mock-doc style in favor of a more straight-faced, talking-heads approach to their deception. According to the film, fictional New Zealand-born filmmaker Colin McKenzie (Thomas Robins) not only shot dozens of unseen silent shorts, including a feature-length retelling of the Biblical story of Salome, but even photographed another local man, Richard Pearse, making the first airborne flight of a powered aircraft, months before the Wright Brothers. In hindsight, it’s amusing to learn that unsuspecting casual filmgoers were convinced by Jackson and company’s deadpan commitment to this little black-and-white lie.

From the Journals of Jean Seberg (Mark Rappaport)

Actress Jean Seberg committed suicide in 1979, but in Mark Rappaport‘s absorbing pseudo-documentary, she speaks to us, channeled through the performance of Mary Beth Hurt, who narrates her tragically true story. In 1970, Seberg found herself a victim of FBI badgering, derided by J. Edgar Hoover for her support of the Black Panther movement. False news stories circulated in the press, stating that Seberg was pregnant with the child of an African-American man, an incident that led to Seberg’s miscarriage soon after. The highs and lows of the actress’ life and career are illuminated with painful clarity, used by one husband and then another, her celebrity merely employed to attain greenlights for increasingly forgettable projects. Again and again, she assists her husbands’ careers, but did anyone ever think or care to ask Seberg what she wanted? Not until it was too late. Charting Seberg’s career with shocking insight, Rappaport’s film takes its audience inside the wounded heart of this cinematic icon. You’ll never look at that Breathless poster on your friend’s wall the same way again.

The Imposter (Bart Layton)

A powerfully engrossing and palm-sweatingly suspenseful semi-dramatized documentary, The Imposter is, in many ways, a masterclass in the deceptive art of storytelling. We begin with a young, blond-haired child, Nicolas Barclay, living a happy life in south Texas until, one day, he vanishes without a trace. A few years pass and the Barclay family receive a phone call, informing them that Nicolas has been found alive and well in Spain. Overjoyed to be reunited with their lost son, the Barclays welcome Nicolas home, seemingly oblivious of the fact that he now has dark brown hair and speaks with a thick French accent. What happened to him during this passing time? Director Bart Layton builds a frenzied sense of tension with a canny use of dramatic recreations of events, interspersed with real life testimony from the endlessly peculiar Barclay family, throwing light on one of the most shockingly twisted (in more ways than one) true stories ever put on film.

Little Dieter Needs To Fly and Fata Morgana (Werner Herzog)

As a young boy, Dieter Dengler witnessed the bombing of his small German village from the ground, even managing to make eye-contact with a passing pilot from his bedroom window. The sight haunted Dengler. “From that moment on, Little Dieter needed to fly,” Dengler laughs, recalling the incident which birthed a trajectory that would end with him trapped in a Laotian P.O.W. camp. As Dengler’s story unfolds, director Werner Herzog employs what he refers to as “stylizations,” narrative techniques that assist in conveying the subject’s interior emotions. Beyond the fact that the film was shot twice, in German and English, Herzog explained in Paul Cronin‘s book, Herzog on Herzog: “Everything in the film is authentic Dieter, but to intensify him, it was all reorchestrated, scripted and rehearsed.” The intensification included Dengler carefully describing the image of jellyfish as representing death to him, an unforgettable and fictional touch straight from the Herzog’s imagination.

Not unlike the director’s earlier film, Fata Morgana is a mesmerizing and alien glimpse of the landscapes and inhabitants of the Saharan desert, which cineaste Amos Vogel described as “a cosmic pun on cinéma vérité,” the line between fact and fiction missing. Herzog originally conceptualized the project as science fiction, as if a visual document had been made and left behind by a visiting extraterrestrial. The film even includes several haunting shots of real-life mirages captured in the sickening desert heat. One particular mirage appears to be a tour bus flanked by a handful of tourists, which floats dreamily above the sand. It’s only when Herzog and company rushed in the direction of the bus, desperate for water, that they realized that it was never there. And yet the ghostly images are there to be seen, burned onto celluloid.

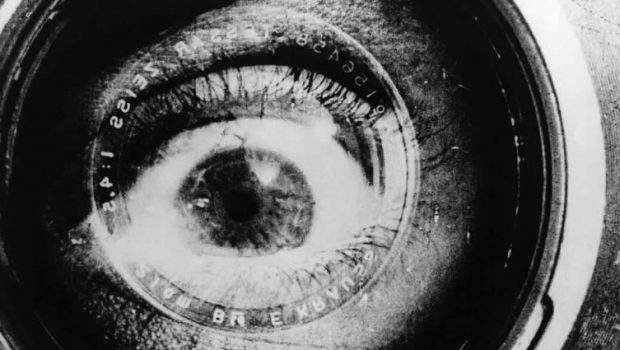

Man with a Movie Camera (Dziga Vertov)

An avant-garde snapshot of unfiltered daily life in Soviet Russia intermingling a kaleidoscopic cavalcade of explosive cinematic techniques, Dziga Vertov‘s Man with a Movie Camera is a visually dazzling film made up of images coming from every direction. Bored with the tradition of narrative filmmaking, Vertov set out to make a film without theatrical drama or narrative indulgence, a limitless onslaught of imagery intended to create an exclusively cinematic language separate from the dusty old contrivances of theater and literature. Capturing real life and sometimes provoked reactions from its subjects, the eye-popping experiment that is Man with a Movie Camera toys with the form, expanding the reaches of the medium beyond hollow wiles found down at the picture show.

Medium Cool (Haskell Wexler)

Medium Cool finds a hypnotic middle ground between dramatic storytelling and documentary realism in its depiction of the lives of a man and woman tossed together and torn apart, placed against the backdrop of the infamous 1968 Democratic National Convention protests. John (Robert Forster) is a cameraman for the local news who we meet photographing the wreck of a car on the side of the road. The female driver lies dying next to the vehicle, but John simply photographs her without offering help and walks away, having captured the footage he needs. Writer-director Haskell Wexler‘s stunningly photographed feature debut is a film obsessed with style and aesthetic, forcing its fictional characters onto a page of history, capturing the feel of the era as well as its sadly flawed protagonists’ psyches. The film even builds to an unforgettable moment in which the cinematographer is teargassed by police and a voice calls from off-camera, “Look out, Haskell, it’s real!” Powerfully enduring in its sense of location and immediacy, Medium Cool is a landmark of late-’60s counter-culture cinema.

Nanook of the North (Robert J. Flaherty)

The life and culture of a Inuk family and their titular patriarch becomes the focus of Robert J. Flaherty‘s film, perhaps most notable for being considered the first feature-length documentary ever made. Heavily criticized for misleadingly portraying staged scenes as reality, Nanook of the North is one of the earliest examples of fact and fiction blurring for the sake of cinematic invention. The scenes shown therein were staged for camera in an attempt by Flaherty to illuminate the daily life of the Inuk ancestors of Nanook, whose real name was Allakariallak. Instead of the rifle Allakariallak would usually employ on his hunting expeditions, he was encouraged by the filmmaker to use knives or spears, reenacting long-out-of-date techniques for the intention of cultural preservation. Even today, the warmly insightful Nanook of the North remains a captivating historic snapshot of life in the Canadian wilderness.

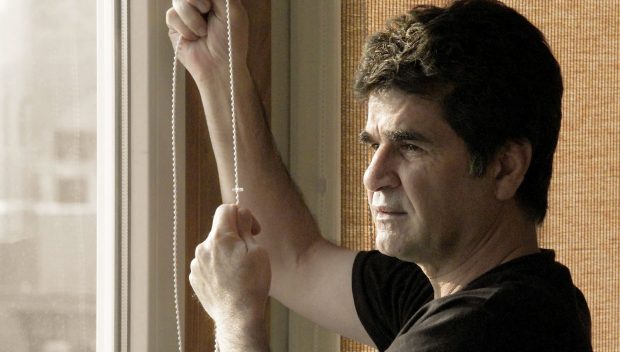

This Is Not a Film, Closed Curtain, and Taxi (Jafar Panahi)

The films of Jafar Panahi are so full of life, invention, and creativity, that it’s a tragedy to realize he was banned from filmmaking by the Islamic Revolutionary Court in 2010. Panahi was accused of colluding to commit crimes against the state with the intent of creating anti-Islamic propaganda as a result of his attempt to document the upheaval following the 2009 re-election of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. Placed under house arrest, Panahi set about making This Is Not A Film, a docu-diary project shot in his home detailing his life after release, which had to be smuggled out of the country on a flash-drive baked inside a cake in order to get to the Cannes Film Festival.

As the real-life complexities of Panahi’s situation pushed against his artistic intent, he pushed back, incorporating them within his work. His next film, Closed Curtain, which focuses on two distraught people hoping to evade detection of the authorities by hiding inside a house, always keeping the curtains drawn, was also shot in Panahi’s home. This technique had served Panahi well in the past, as with his earlier work, Offside, which was filmed in part during the the Iran-Bahrain qualifying match for the 2006 FIFA World Cup, as seen in the film.

In Taxi, Panahi takes a leading role as himself, driving a cab through the streets of Tehran, picking up passengers whom, we slowly realize, are scripted actors. Yet driving the real streets of Tehran can hardly be scripted, and life seeps into the car in beautiful and surprising ways. Panahi’s real niece, Hana Saeidi, appears as herself in the film, an innocent child utterly curious about the strange and confusing world she sees outside the windows. After Taxi was awarded with the Golden Bear at the 2015 Berlin Film Festival, Hana accepted the award on behalf of her uncle, who remained under house arrest in Iran.

Kate Plays Christine is currently playing at the IFC Center and will be expanding in the coming weeks.