Halfway through Phuttiphong Aroonpheng’s hypnotic feature debut, Manta Ray, two men put up Christmas lights around an unadorned riverside shack. They’ve known each other for a while, but seldom speak: one (Wanlop Rungkumjad) is an unnamed Thai fisherman with dyed blonde hair; the other (Aphisit Hama) is a mute man whom the fisherman has found agonizing in a remote stretch of mangroves by the border with Myanmar, and has taken home to look after. The lights are to serve as decoration for a party the two are throwing that same night, but the sun is still high on the horizon; smiling ecstatically at the makeshift disco, the fisherman suggests the two should nap to make the day go by faster. And so they do.

Watching the two young men fall asleep side by side and later sway to a mesmeric electronic tune, their eyes agleam with happiness as they dance together–the night already high and dark above them, the room flickering under the lights and disco ball–I was struck by the ineffable mix of tenderness and humanism that permeates Aroonpheng’s first film. Manta Ray is a delicate, poignant exploration of otherness, a moving and lyrical ode to kindness that never once gives in to preaching, but retains an engulfing, magical aura.

Dedicated to the Rohingya people, a stateless ethnic group that’s suffered decades of persecution in native Myanmar and whom Hama’s voiceless character symbolically embodies in all its powerlessness (albeit the connection between the mute refugee and the Rohingya is never made explicit), Manta Ray zeroes in on the relationship between two strangers mired in a land of ancestral conflicts. Having reiterated at length the guest can stay at his place for as long as he wants, the Thai lad gives him a name (Thongchai, after popstar “Bird” Thongchai), teaches him how to swim, how to ride his sidecar, and how to attract giant manta rays with the shiny gems scattered around the mangroves where he was washed ashore. Though a case could be made to read the blonde fisherman’s actions as motivated by a certain attraction toward Thongchai (moments of sexual tension abound, albeit the flirting is reined in somewhat by a near-brotherly and omnipresent affection), I fear such interpretations may gloss over the selflessness underscoring his astonishing compassion. More than tending to Thongchai’s wounds, the recovery the young fisherman offers his housemate transcends physical attraction, and lands on a near-otherworldly terrain–a re-humanizing process whose ultimate goal is the restoration of an unnamed man’s dignity and identity.

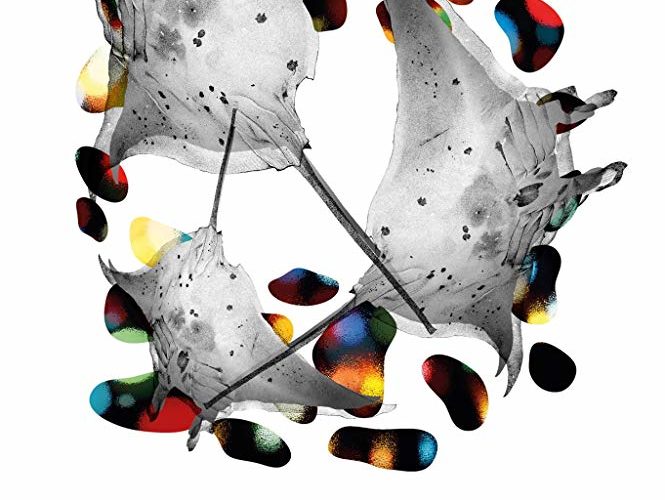

Rungkumjad’s androgynous beauty lends the fisherman an angelic physique du role that bodes well with the Good Samaritan he embodies upon rescuing Thongchai. But the pity belies an overdue atonement. Long before the two meet up, Manta Ray opens with a mysterious rifle-wielding man (Sanit Pasingchop) wrapped in fairy lights and roaming through a forest dotted with sparkling colored bulbs; moments later, a hooded Rungkumjad is shown next to other accomplices as he digs graves in the forest, waiting to bury unidentified refugees. It’s a nighttime gig which, unbeknownst to Thongchai, the fisherman performs in between his fishing trips, at least until he phones his mysterious boss (the rifle-wielding man?) to say he’ll quit, and disappears a few days later.

From here onward, Manta Ray becomes Thongchai’s show, as the refugee wanders around an uncharted territory searching for his friend–a quest that ends after the Thai’s estranged wife (singer Rasmee Wayrana, in an assured acting debut) shows up at the shack, mourning the husband’s absence by having Thongchai act as a surrogate, altering the migrant’s looks until he effectively resembles the fisherman–down to the flocks of dyed blonde hair.

All its compassion notwithstanding, Manta Ray thrives on its magical and mysterious subtext. Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s acolytes will spot familiar terrain in Aroonpheng’s excursions into symbolism–indeed, at its most lyrical, Manta Ray breathes with the same magical realism of Weerasethakul’s 2010 Palm d’Or winner, Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall his Previous Lives. There is something seriously eerie in Nawarophaat Rungphiboonsophit’s cinematography, especially when the camera careens around the forest in the dead of night, a perturbing feeling amplified by the haunting soundscapes composed by French duo Christine Ott and Mathieu Gabry. An established cinematographer with a number of features already under his belt (including two 2015 Rotterdam Film Festival entries, The Island Funeral and Vanishing Point), Aroonpheng’s crafts a visually stupefying first feature. Nestled inside a verbally parsimonious script (it takes over nine minutes for the first word to be uttered) are shots of spell-binding beauty: watching the forest’s floor billow to life in a carpet of multi-coloured bulbs, the whispers of invisible refugees filling the night with a symphony of voicelessness, was among the most memorable moments from this year’s festival circuit.

Manta Ray screened at the Tallinn Black Nights Film Festival.