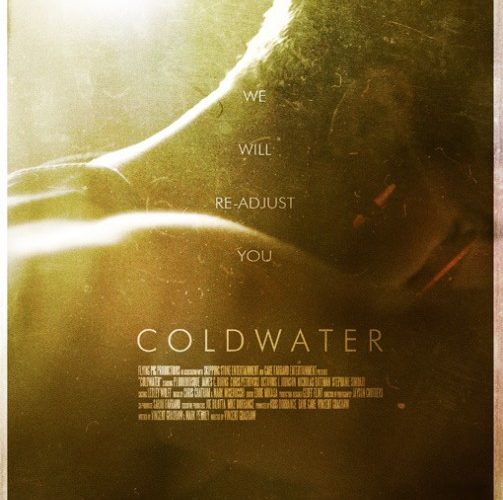

Whether true or not, hearing writer/director Vincent Grashaw wrote the first draft of his debut feature Coldwater right after graduating high school in 1999 was an intriguing tidbit for my preconceptions to process. A producer on hipster darling Bellflower—a movie I didn’t warm towards—its success may have been the sole push needed to greenlight this more than a decade-long journey from script to screen. Snap judgments started manifesting in my mind to dismiss it as a juvenile work only made possible due to a built-in marketing windfall of a “by the producer of” credit instead of giving the guy the benefit of the doubt. Maybe Grashaw spent those twelve years directing well-received shorts so he could continue tightening his raw, emotional script—now a collaboration with Mark Penney—and polish his technique behind the camera before making the final piece perfect.

While he may not have succeeded in perfection, Grashaw did do his passion project justice after waiting this long. It’s an assured debut with a fearless desire to carefully disseminate the information needed to process the whole in calculated portions. Rather than show the heinous events leading to young Brad Lunders (P.J. Boudousqué) being sent to A.J.R.S. facility Coldwater—where twenty-five miles of wilderness separates it from the nearest town—we’re thrown into the action blind and without warning. Just as this troubled kid is woken by the cold steel of handcuffs dangling above his face before getting picked up and dragged into a window-less van while his mother compliantly looks on, we too are disoriented until the sunlight returns and the privatized boot camp devoid of rules or regulations takes over.

Run by an ex-Marine Colonel named Frank Reichert (James C. Burns), what initially appears to be a legitimate institution utilizing tough love and manual labor to reform delinquents into upstanding citizens proves to be anything but. Reichert is introduced as a well-meaning authoritarian who takes pride in his work and the fact many “graduates” stay on and work as “counselors” rather than assimilate back into regular society. This should have been the red flag to uncover exactly what was going on but humanity’s propensity to see the good in people always finds a way to shield us from the truth’s horror. Coldwater may have been created on honorable principles but any visage of such a time has now been twisted into catchphrase and public relations rhetoric so its breeding ground for torture can remain intact.

These state- and private-run facilities have become factories manufacturing soldiers of unchecked violence without an enemy to fight besides the new blood sent into their killing fields every day. After what could be years of extreme physical duress building rage and anger into an uncontrollable destructive pool anxious for release, it’s no wonder so many stay to inflict the same pain on others in the name of rehabilitation. Not all establishments are like this—my cousin worked at one more akin to school than prison despite its middle of nowhere locale and barbed wire fencing warning off potential escapees—but knowing in your heart most are is a tough pill to swallow. I’d be interested to learn what eighteen-year old Crashaw experienced to impassion him towards exposing these atrocities because the emotive power on display is fierce.

The beauty of his lead character Brad is how the incident earning him a place in the wilderness scared him straight internally without the need for the external abuse. He arrives to Coldwater a changed man full of regret and already removed of the tools that inflicted his pain. A modicum of what’s to occur in captivity is warranted—his place under the thumb of Reichert and cronies not necessarily unjust. However, when extended runs in the heat without proper hydration turn to vicious assaults on behalf of counselor Powell (Tommy Nash), Brad’s remorse becomes a badge of honor and compassion for those at his side. Not wanting to fight and make his situation worse, the temper and strength that landed him there also deem him the best candidate to expose the inhumane conditions at play.

Over the course of two years we witness a suicide attempt, a failed escape, brutal retribution, amputation, and a complete disregard for human rights. It’s the type of over saturation of tragedy we need to understand the violence utilized by power-hungry men to beat down weaker foes with more than just a hint of a glimmer in their eyes. The duration as well as the victims’ changing faces from Octavius J. Johnson’s Jonas, Clayton LaDue’s Trevor, and Brad’s old friend Gabriel (Chris Pretovski) helps such a laundry list of injurious conditions appear realistic. We watch as our lead learns to pick his battles, work both sides, and build trust in order to acquire a position of authority. And just as the end appears near his past comes flooding back at the camp’s tipping point.

Coldwater lives or dies by the dynamic between Boudousqué and Burns ebbing and flowing from nemeses to partners and back again as the latter begins to lose control. It’s a cat and mouse game with government officials threatening sanctions that never evolve into anything tangible as the boys discover their fate rests in their own hands with a nightmarish Lord of Flies-esque climax that would render any parent who ever thought of voluntarily sending their kid away to one of these establishments moot. In what becomes its only possible outcome, Grashaw exposes the complicity of local law enforcement, their inability to do anything without concrete evidence anyway, and the veritable military states these satellite facilities construct away from law and mandate when fear creates monsters on both sides.

It’s a star-making turn for Boudousqué’s stoic, Ryan Gosling look-alike and a great forum for the likes of Burns’ totalitarian and Nicholas Bateman’s embodiment of a system gone wrong transformation from oppressed to oppressor. With a taut progression towards an impactful inevitability, Grashaw gets his point across while also telling a riveting tale. Sadly, a desire to shock and surprise proves disastrous when deciding to end the film with a reprise finale of revelations exposing lies we’ve already seen through. Nothing is gained in the final ten minutes that Boudousqué’s emotional breakdown hadn’t already earned—show us his actions while he lies to the police, not after in a waste of time. Less is more and the transparent tricking of your audience can’t help but sully whatever well-composed drama came previously.