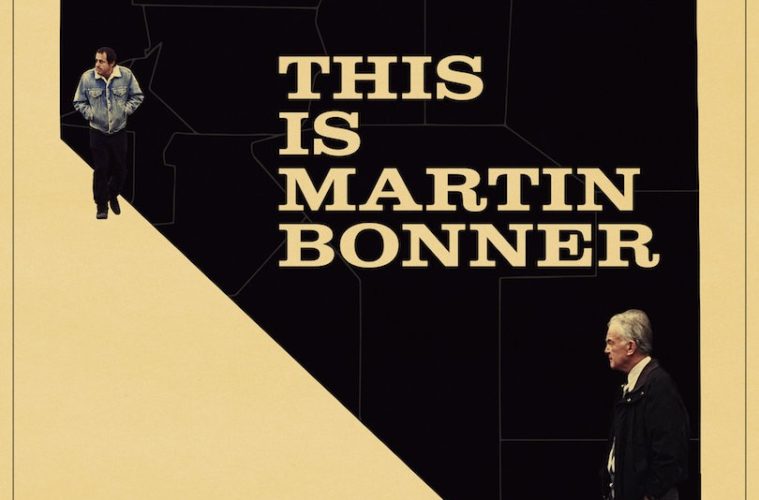

We’re all human beings. I think this is the message writer/director Chad Hartigan shares in his sophomore effort This is Martin Bonner. We make mistakes, we pay for our crimes, and we live our lives with the hope we can redeem ourselves to make things right. Demons aren’t something evil people have a monopoly on—in fact it’s those with compassionate hearts and strong moral consciences who are probably haunted by them most. We’re dealt second chances often enough to render the word “second” moot, but it’s what we do with them that matters. Everyone on this earth has the capacity to make himself a better person and in turn inspire those around him to strive for more. But no one will believe it’s possible if we don’t believe it ourselves.

For Martin Bonner (Paul Eenhoorn), this opportunity comes in the form of a charitable, Christian program that puts him in touch with ex-cons recently released from prison in order to help re-assimilate them into society. A long-time theologian, his arrival to Reno, Nevada has come while at a crossroads in his faith—something a brilliantly orchestrated opening scene with Demetrius Grosse’s inmate Locy helps exacerbate with a changed tune from grateful for the help to “how will this shorten my sentence?” Martin can’t help but notice how Jesus Christ has become almost as detrimental to assisting troubled souls as he crucial. People have become jaded to the prospect of religion to the point where its inclusion breeds suspicion rather than hope. Why wouldn’t he therefore find himself at odds with it?

On the flipside is Travis Holloway (Richmond Arquette)—a man remorseful for the crime that put him behind bars for twelve years who’s bought into this outreach program to help steer him in the right direction. Also at a crossroads, he’s a man with little faith wondering whether he should embrace God closer to his heart. Watching the happiness of ‘mentor’ Steve (Robert Longstreet) and his wife (Jan Haley) opens him to trying, but he remains unsure without having received that all-powerful vision of spiritual love to show the path. While indebted to Steve for his kindness, giving himself over to that life only instills a sense of personal fraud. For this reason Martin is more accessible and understanding of his plight—both alone in a new world, not knowing what the future may bring.

It’s a friendship neither truly seeks, but one that can’t help forming once they learn the similarities of their predicaments. Hartigan shows us the minutiae of their day-to-day with a keenly static eye watching from afar with slow zooms and pans capturing the world around them. Equal parts lonely and appreciative of the time for contemplation, Martin and Travis wade through the unexpected cold weather of Reno’s desert and the charm it possesses outside the main strip. It’s the first sense of freedom both have found in many years—the latter being incarcerated and the former now time zones away from his grown children and ex-wife in Maryland—so they’re still looking to find their way. And while they weren’t each other’s first choice for a friend, they surprise each other nonetheless.

As a whole, This is Martin Bonner is a subtle piece of art getting at the heart of the human condition. A character-driven tome, nothing works if not for the resonate performances at its center. There’s a sadness in both Eenhoorn and Arquette’s faces that’s wiped away only by the easy smiles formed when their preconceptions are proven wrong. Neither has the answer for how to live their lives from this point on and both find themselves hovering in a sort of purgatory that risks being flooded by cynicism and pessimism if not careful. But they’re willing to trust each other enough to divulge desires and insecurities, learning their respective drive towards reconnecting with a child they’ve disappointed in the process. It won’t be easy, but the smallest glimmer of hope provides promise.

There’s also a sweetness to them that’s completely authentic as little glimpses at Martin rocking out to an eight-track of his old Australian rock outfit Kopyrite, (Eenhoorn actually did write and perform the song “Genevieve” in the 60s), or Arquette’s Travis slouching with a cigarette as the lights of Reno shimmer in the distance give us a sense of who they are in the quiet of their own minds. It’s almost as though they’re unable to grant themselves permission to be happy—to truly exist for themselves without the albatross of a committed crime or God on their shoulders. And somehow, despite the disappointing signs leaning towards a trapped life being all they can emotionally afford, they find the other becoming that important example of courage against adversity to keep moving forward.

Hartigan’s story is crafted with extended moments that add up to explain the power of tiny victories and genuine smiles in the context of an existence unavoidably full of much bigger tragedy. We witness the gentle embarrassment and fear of life—the anxious insecurity threatening to derail every hope at reconciliation and happiness we often don’t believe we deserve. Watching Arquette awkwardly shift in his diner seat and grasp at straws to engage the 24-year old daughter he hasn’t seen in over a decade (Sam Buchanan) is heartbreaking. Seeing Eenhoorn’s face of soft frustration and helplessness at his inability to get his son on the phone is to catch a look of undying love. These are real people surviving the struggle against the pain to which too many succumb—striving to be the best they can.

This is Martin Bonner is available on VOD today and in limited release.