One of the more discussion-piquing results of contemporary cinema’s ever-increasing implementation of technological advancements is the way these innovations can often distort the essential quality of a film. James Cameron‘s Avatar is a perfectly applicable and illustrative, if over-referenced, example for this assertion — a breathtaking, engulfing visual atmosphere (even on a 2-D screen) it has; a rich, complex, moving story with lasting characters it lacks. In other words, the historic visual achievement is undermined by a simplistic story — hardly a lamentable fault by any means (I’d still recommend Avatar to any beating heart), but one that takes on a more observable presence once people make the (perhaps unconscious) choice of overlooking the mediocre by overstating the remarkable.

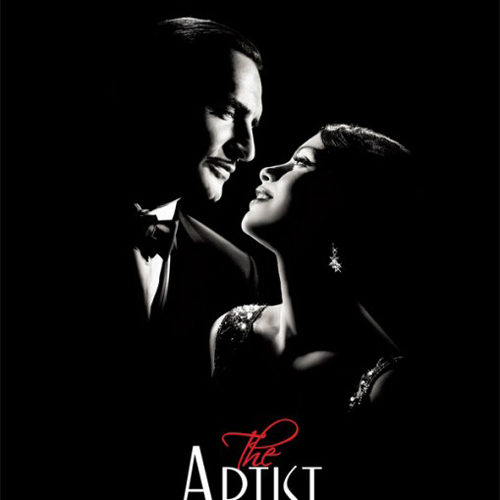

Michel Hazanavicius‘ The Artist, then, which has been sweeping up festival awards across the country, provides a fascinating, compatible example to the innovation of Cameron‘s film. The Artist is technically revolutionary in a different way — rather than pointing to cinema’s road ahead, Hazanavicius‘ black-and-white silent film (save for a lush score from Ludovic Bource) harkens back to the roots of motion pictures, proving, during a time period when it’s easy for most people to forget, that films need not have color and sound to achieve an absorbing quality.

Nevertheless, it’s Hazanavicius‘ daring approach that is distracting people from the rote, formulaic storytelling on display. Lead actor Jean Dujardin, playing Hollywood’s most-beloved 1927 silent-film star George Valentin, only needs to smile once for you to buy into the irresistible charm of this thing, but that doesn’t escape the fact that his character is treated with exhaustingly thin strokes.

At the outset, he’s a beloved maven loving every second of his attention-getting lifestyle, but once studios begin churning out talking pictures, he ignorantly refuses to adapt to the changing times. (It’s never really made clear that his talent isn’t adaptable — his blind refusal to change, rather, is his main hindrance.) So, for most of the rest of the picture, Dujardin‘s abilities are restricted to solitary sulking, a move that ultimately reduces the character to a one-dimensional representation.

Bérénice Bejo, Dujardin‘s pure stunner of a co-star, goes through a similar trajectory. The actress is as lovingly expressive as anyone could ask for, but her role doesn’t give her many opportunities to show signs of nuance. She’s simply the opposite embodiment to Dujardin‘s weathered silent-film magnate — as Peppy Miller, she starts out as a simple movie fan, then begins auditioning for supporting roles, and, finally, strikes it big with the talkies. She has the bottom-to-top curve; Dujardin‘s George has the top-to-bottom one. Throw in the fact that a romantic spark is ignited between these two, and you can probably guess where this one is going to end up.

This isn’t to say that the charming characteristics of the film should be dismissed. After the director’s two witty, technically savvy spy-genre spoofs — OSS 117: Cairo, Nest of Spies and OSS 117: Lost in Rio — it comes as no surprise that the craft aspects of The Artist are uniformly immaculate. These aspects, combined with the natural appeal of Dujardin and Bejo, make the film an easy one to enjoy, and an easier one to recommend. (I have a hunch that it’ll make a solid killing at the box-office, despite its distinctly dated sensibilities.)

But that isn’t enough to overlook Hazanavicius‘ reserved screenplay. The film delivers visual and technical panache in spades, but that doesn’t escape the fundamental simplicity of the material. There is one sequence in the film — the adorable, inventive meet-cute montage between George and Peppy — that stands out as a marriage between technique and content. It’s the prime example of Hazanavicius the writer rising to the creative level of Hazanavicius the director. The rest plays like a director who wanted so badly to embrace cinema’s foundations that he forgot to focus on the specificity of his own story in the process.

Indeed, the film often parades as an homage to cinema’s origins, but, in doing so, it only makes its own limitations more evident. At the start of the film, for instance, George is married, and eventually we get a Citizen Kane-recalling sequence that delineates the marriage’s downfall through the exclusive presentation of their breakfast-eating habits. But this isn’t really an homage, per se, as much as it is a pure reenactment of a beloved sequence. To take it at face-value as a self-reflexive wink to Orson Welles‘ classic is one thing, but to so obviously borrow from a previous film during a crucial juncture such as this one — indeed, the breaking-up of George’s marriage in this film is no glossed-over matter — feels like a misguided artistic choice. Again, it’s as if Hazanavicius is more intent on capturing a lovingly old-fashioned atmosphere than actually depicting his characters with consistent honesty.

As wonderful as it is that Hazanavicius — the furthest thing from a gold-plated name within the industry — was able to create something like this in today’s day and age, his finished product nevertheless rings of reductive conventionality. As a film lover, I responded much stronger to the messy, less-formulaic magic of Martin Scorsese‘s Hugo. The Artist deserves to be seen, but I’m not sure it’s the kind of thing that deserves to be loved and lauded with equal measure.

The Artist is now in limited release.