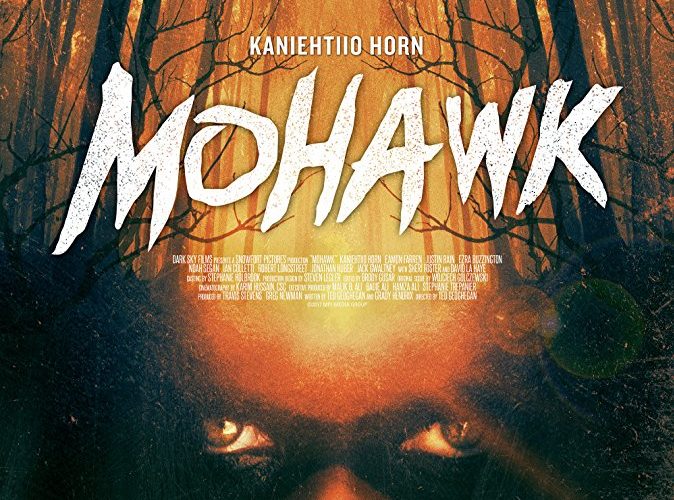

In director Ted Geoghegan’s debut We Are Still Here, the subtlest horrors came from quiet images of nature. Within its context, creaking trees and beautiful landscapes instilled an insidious sense of indifference to the angered spirits born from injustice inside the walls of an old home. In his follow-up Mohawk, Geoghegan and returning cinematographer Karim Hussain allow nature to envelop almost every frame, as a narrative of injustice now spills across a dirt-caked landscape of oppression, blood, and cultural roots.

These roots belong to the titular Mohawk tribe, whose land has been invaded by a warring America and Britain, with battle lines and blood drawn in soil belonging to neither side. Angrily caught in this crossfire are two members of the Mohawk tribe, Oak (Kaniehtiio Horn), and Calvin Two Rivers (Justin Rain), along with their British companion and lover Joshua (Eamon Farren). Pressured to take sides in a war designed to disregard their perspective, the dwindling Mohawks find themselves outnumbered and on the run in their own rapidly-changing home.

After a rocky beginning, Mohawk settles into its strange tonality and movement, casting a gnarly spell as its stripped-down stylings evolve into authentic grunge. What at first feels put-on becomes lived-in; as actors sink into characters and grisly displays of violence allow for direct confrontations with suffering, Mohawk offers a raw and earnest condemning of the white man’s historical and ever-present atrocities that feels particularly urgent today. Shot in only natural light on actual Mohawk land, Geoghegan makes it clear that even with little means he can still deliver sheer affect.

The visual language here melds the stoicism of the aforementioned nature imagery with a freneticism usually at home in war documentaries. These chaotic frames weave about the forest, framing combatants as if through hurried luck. This naturalistic style favors Mohawk’s bare aestheticism, with Geoghegan leaning into the elemental struggle to survive. This struggle is depicted mostly through the eyes of Oak, whose piercing gaze holds both her compassion and blossoming anger.

These eyes are essential, as what begins to feel most poignant in Mohawk is the concept of the gaze, the witness. In one particularly grueling sequence, Oak looks on as a friend is tortured; frozen with no ability to help, but filled with too much care to look away, she becomes bound in the role of the eyewitness, momentarily inactive, but not passive. Compelled to behold cruelty, Oak represents those in history who have found themselves powerless and voiceless against imperialism, against atrocities, against injustice. Yet as a witness, Oak is compelled to honor those fallen, assured of rebellion and change as she moves forward.

Her journey is the heart of the film, and Horn manages to carry the weight and love of Oak in her eyes, even as she is forced into unrelenting revenge and more overt physicality. Around Oak are her two lovers, yet she is never objectified, remaining instead a woman not defined by the men she shares her company with. This company is decidedly less interesting than Oak herself, though it is refreshing to see a white man utilized as an emotional propellant for a non-white, female protagonist, even if Joshua’s presence feels somewhat unnecessary in Oak’s overall narrative trajectory.

To some degree, Geoghegan seems to know this, as he makes the smart decision of usually favoring Oak’s gaze over others. This includes one memorable composition where Oak’s face remains the focal point, while Joshua’s eyeline is cut off, leaving only his mouth visible while he speaks. This emphasis on Oak’s perspective, devaluing her white companion, holds thematic implications.

Indeed, Geoghegan and co. handle much of Mohawk’s narrative and political allegories not unlike how the desperate Mohawk deliver their attacks–with less interest in trading blows than in a direct, blunt-force series of strikes. The conductors of imperialism spread pain and destruction to the oppressed and disenfranchised, and they deserve righteous consequences for their horrors. As the narrative progresses and blood is shed with increased frequency, it begins to feel like some sort of divine, inescapable force barrels toward those who take what is not rightfully theirs.

It has blood, guts, and bad guys, but Mohawk’s most impactful moments come not in the violence inflicted, but in what that violence represents. In these painful, powerful moments of oppression and refusal to look away, Mohawk steps beyond its minute scale and modest restraints, entering into mythic and purposeful territory. While some of its dramatic gestures fall short or feel stilted, it is through sheer pervasive commitment to its characters and message that Mohawk’s grimy power is able to shine. Here, an unfortunately timeless message stands in a time divided: there’s hell to pay.

Mohawk opens in limited release and on VOD on March 2.