Bellflower is a tough film to describe, which might exactly be its raison d’être. Nothing about it is expected. Take the premise, for example: Woodrow (writer/director Evan Glodell) and Aiden (Tyler Dawson) are two guys in their 20s who just want to live out their dream in the beauty of California. That dream? To prepare themselves for the apocalypse cresting just over the horizon which will undoubtedly resemble The Road Warrior.

This description assuredly brings up visions of beefed-up maniacs, wearing codpieces and goggles, marauding down the Hollywood Hills, reaping holy destruction upon the land. Instead, you find two grown-up middle schoolers who have graduated from lighting cans of hair spray on fire to firing shotguns at propane tanks, mixing up “escalation” with “maturation.” This arrested development extends into their social well beings as well. Aiden talks a big game to mask his sanguine and innocent nature. Woodrow is shy and introverted, especially when he meets Milly (Jessie Wiseman) at a bar during a cricket eating competition, easily one of film’s most bizarre “meet cutes”. When Milly meanders over to Woodrow at the bar after the competition, he offers to buy her a drink but can’t muster the gumption to raise his head and look her in the eyes. I think he likes her!

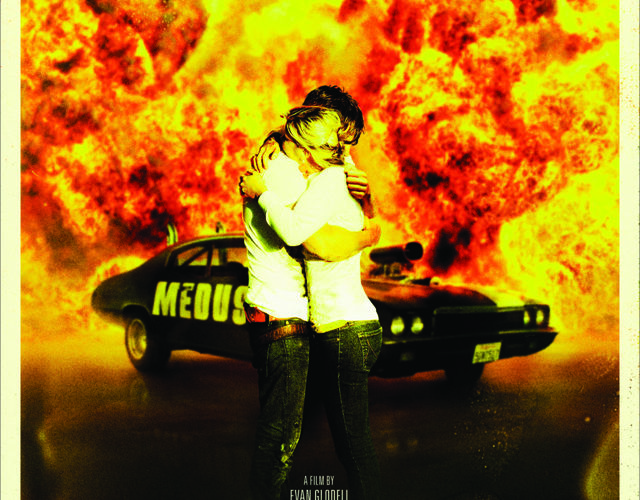

We follow this budding romance in a very amiable environment. The film is loose and fun, filled with quick banter and a genuine connection between the cast members. Woodrow courts Milly in wonderfully innocent ways. On a car trip, Woodrow cuddles with Milly in the backseat of his car and asks if she’d like to be his girlfriend. You almost expect Fonzie to hit the jukebox just alongside the road. This new woman in Woodrow’s life subtly drives a wedge in his friendship with Aiden. Whoever is he to make a flamethrower with, let alone a bad-ass muscle car named Medusa that shoots flames out its exhaust pipes from which they could survive the end times? So he begins to court Courtney (Rebekah Brandes), Milly’s cute friend.

We follow this budding romance in a very amiable environment. The film is loose and fun, filled with quick banter and a genuine connection between the cast members. Woodrow courts Milly in wonderfully innocent ways. On a car trip, Woodrow cuddles with Milly in the backseat of his car and asks if she’d like to be his girlfriend. You almost expect Fonzie to hit the jukebox just alongside the road. This new woman in Woodrow’s life subtly drives a wedge in his friendship with Aiden. Whoever is he to make a flamethrower with, let alone a bad-ass muscle car named Medusa that shoots flames out its exhaust pipes from which they could survive the end times? So he begins to court Courtney (Rebekah Brandes), Milly’s cute friend.

It feels like standard indie-mainstream fair: kooky, eccentric manchildren get a dose of reality from the other sex and learn that growing up is O.K. It could make one think of all the cute double-dates they could have in an abandoned lot outside Ventura. But that would belie the subtle feel of dread that permeates this film throughout. The opening shows a quick version of the events in the film’s second half, which offers a glimpse into where this story could possibly go. From the opening section, it seems nearly impossible that we’ll get there.

But soon Milly starts to act like the girl that she warned Woodrow he shouldn’t date, and less like the idealized partner he thought he was getting into. The insular world that they exist in–one that doesn’t seem concerned with things like “jobs” or “responsibility” gets more and more infused with alcohol, with spite, with disappointment. The second half of the film is the bad part of town you don’t realize you’re driving into until you notice the scenery that envelops you. And believe me, it gets bad.

This is a film that keeps its dark promises. You’re shown a hand-crafted flamethrower, it is used. You’re shown the creation of the muscle car to end all muscle cars, the fearsome, fire-breathing Medusa, and it tears up the streets. You’re shown two boys with destructive tendencies flying through their minds, and they will live up to them, no matter how disarming the opening is. It’s something Chekhov would be proud of. We’re promised an apocalypse, and we bare witness to the annihilation of Woodrow’s world.

Bellflower‘s reality/surreality is shown amidst a heavily stylized look, captured by Joel Hodge, using two optical systems and a camera designed specifically for this film, playing with the focal range and making sure that nothing ever looks clean or simple. Aiding to this uneasy feeling is a New Wave style of editing that keeps the viewer a bit off balance. Juxtaposed against all of this is a very naturalistic style of acting, even as the script pushes these characters to some rather outlandish acts. Indeed, the final bits of the violent crescendo are so extreme that it can elicit snickers.

Bellflower‘s reality/surreality is shown amidst a heavily stylized look, captured by Joel Hodge, using two optical systems and a camera designed specifically for this film, playing with the focal range and making sure that nothing ever looks clean or simple. Aiding to this uneasy feeling is a New Wave style of editing that keeps the viewer a bit off balance. Juxtaposed against all of this is a very naturalistic style of acting, even as the script pushes these characters to some rather outlandish acts. Indeed, the final bits of the violent crescendo are so extreme that it can elicit snickers.

But as much as I didn’t like the end, I still can’t shake it. The images, the violence, the escalation, and just what befalls the characters I had grown to enjoy and care about so much.

It’s a wonderful magic act: we’re shown the end result, goes out of its way to make us believe that something that extreme isn’t possible, but by the time we get back to the inevitable conclusion, it seems like we’d always been building towards it. This is an audacious debut for a first-time feature writer/director/actor in its scope, storytelling, and ability to stretch a dollar whose imagination and ball far exceed anything else manufactured into our multiplexes this summer.

Sit back, enjoy the ride, and try to not get burned too deeply.