By now, the lengthy following shot to open a film is an art-house approved cliché. But in The Fool, Yuri Bykov complicates the shot in a way that makes it feel fresh again. For one, he begins his shot with characters heard, not seen—not seen at all in the film, that is. There is a man shouting at a woman because her vacuuming makes it hard to watch TV, and then another man walks into the frame, down the hallway toward the camera, and begins interrogating a different woman about money. He leaves while the camera stays with her; we hear the yelling from the first couple again, and then the man we just saw is heard yelling at a third woman about the money. The woman and the camera rush back across the hall as the man’s excessively violent tendencies explode and the women are saved only because of the decrepit conditions of their building.

The thing that saves them is a shock, albeit a welcome one, but closer attention to this first shot suggests that it shouldn’t be. In retrospect, the shot is beginning by emphasizing the poor conditions of the apartment building; tenants can overhear one another from far away and evidently have become accustomed to tuning out what is not important; space is rendered claustrophobically visually as well, as the hallway is shot head-on in a way that flattens the image. We never find out what happens between the couple arguing about TV and vacuuming despite the film beginning with their argument. Instead, Bykov has demonstrated an aurally sensitive environment that exists within a continuous, inadequate space. It’s quite remarkable.

Unfortunately, it’s also the best that the film has to offer. The next scene sees another character, Dima (Artyom Bystrov) pick up on vandalism based on sound that carries less through open-air than open walls, but from then on, when the film wants to harken back to the poor living conditions in corrupt Russia, it tends to do so by dialogue. The narrative develops fairly quickly—Dima is called to investigate the building in which the film opens and concludes it is going to collapse within 24 hours, but the corrupt officials are dumbstruck about what to do because any sensible action will reveal their corruption, ending with jail or worse. The bulk of the film then features the characters—several of them, well characterized and indicative of the country’s absurd bureaucracy—posit, works through, and ultimately rejects through a number of possible scenarios and solutions. At first these developments and intimations are obvious but forgivable, as when one of Dima’s coworkers says that the housing inspector would ignore the building because he pockets inspection money and bribes inspectors to give him a pass, but it quickly gets worse. More than a couple times the narrative will freeze so one character can chide the others for their illegal activities and self-gain or detail the hierarchical and personal dimensions and benefits of corruption.

Nonetheless, the didacticism seems like a clarifying aside rather than a demonstration of the film’s integral theme, laying the groundwork for the film’s thought experiment. To clarify, it helps to look at Andrey Zvyagintsev’s recent Leviathan, another film that demonstrated corruption on various levels over a period of time to illustrate its toll on a Job-like figure. That film seems to decenter or even abandon focus on its ostensible protagonist as a way of demonstrating his helplessness and revealing the corruption. For Zvyaginstsev, the corruption and helplessness are the revelations. No matter what his Job does, bad things will happen to him because of these other people. Even his lawyer, the apparent righteous man, turns out to not be less than upstanding. Bykov, by contrast, seeks to establish corruption and helplessness all at once and to see what happens when a righteous man actively opposes it. The focus is less on the corruption itself than how each visible escalation makes things even worse for our hero.

Even when he catches a break, the next nightmare seems, quite literally, to be closer to home, and thus the film approaches absurdist territory. Dima’s world is not explicitly without meaning, but it is without any prospect of advancement for him and so many like him. His approach in the face of the absurd—to assert basic principles of righteousness, morality, and fraternity—is hard to fault in theory, but Bykov’s imagination and worldview is uncompromisingly bleak. He relies on the didactic dialogue to make Dima’s differences stark, his failure inevitable, and his entire worldview invalid simply because it is impossible, not merely impractical. In this sense, the film takes on an agonizing inevitability somewhat reminiscent of The Death of Mr. Lazarescu, the Romanian social-realist masterpiece from a country whose New Wave is not entirely unlike the latest features of Bykov and Zvyaginstev, at least politically.

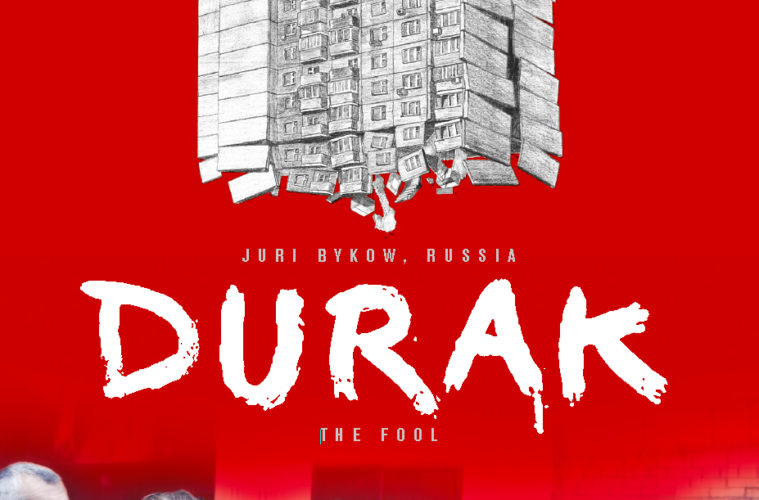

Bykov gets strong performances out of everyone, and the film’s very early scenes and its birds-eye finale, held beyond the point of discomfort, demarcate a great deal of talent. One can only hope that next time Bykov relates his story without resorting to cheap tricks that compromise the power of his images in the process—it can hardly be dismissed as a coincidence that the scenes in which the film most clearly and obviously clarifies its politics are also its least interesting. Bykov clearly seems to position the sociopolitical over the aesthetic despite his talent in the latter field. As such, The Fool is a worthwhile curiosity, not least because of how it condemns the Russian image that has been globally condemned, but rather for the unmistakable cinematic flourishes and the command that Bykov exerts over his narrative.

The Fool is currently screening at New Directors/New Films 2015.