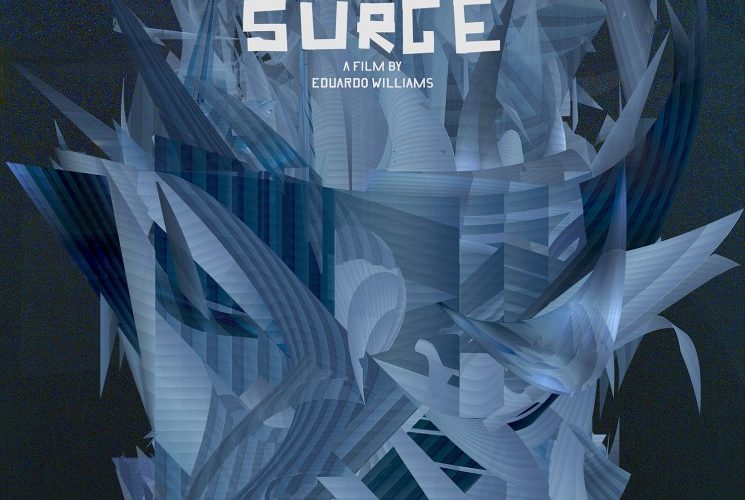

To put it upfront, Eduardo Williams’ The Human Surge is pretty much a film that, by nature, is unlovable. Often blatantly ugly or boring, it’s not so much deliberately confrontational in the way so many experimental films are (or pride themselves on being), but rather risk-taking for the sake of something almost impossible to articulate — even if based in something obvious.

This is a film in which the camera hovers and tracks behind youth so jerkily that it doesn’t appear as much in the vérité tradition as it does from a smart-phone, like a DIY-tribute to Gus Van Sant’s Elephant, or one in which the youth genre is better manifested by speaking more to the means at their disposal. These people under the microscope are part of a Russian Nesting Doll narrative, or rather “network narrative” almost mocking towards, say, a Crash or a Babel in that it shuns coincidence for the clearest of connections.

The film begins somewhat simply in Buenos Aires on Exe, a 25-year-old working at a supermarket. Williams casually captures striking images that straddle the line between documentary and choreography, be it him walking into the city’s flooded streets or a bag of stock seemingly falling from the ceiling at his place of work. Labor is the driving theme, though, his frustration and boredom leading him to quit and try his hand at Internet sex shows for cash. There’s a surprising lack of homophobia from his young male friends seemingly willing to experiment on webcam for the sake of cash.

Upon Exe connecting with another young man, Alf, living in Mozambique and making similar videos, the film ruptures and instantly shifts to his perspective. Echoing Exe in his lack of enthusiasm for a mundane job, he sets out from the city to nature. The next transference, though, is a doozy: in his trek stopping to pee on an ant-hill, the camera then hovers down into this insect colony for a surprisingly extended period. Should you be lucky enough to see The Human Surge at a festival, that sequence is sure to be accompanied by the sound of swinging doors as patrons walk out in droves. Strangely enough, that ant-hill stretch is perhaps the most aesthetically pleasing portion; the camera movement graceful, the space almost geometric.

Yet that’s not the end of the line, eventually pulling out of hill and into the Filipino jungle, following a family at least partaking in some leisure time — only with the constant query of where to find the local cyber café. Technology and connectivity loom in the wilderness and, yes, you can say it — How We Live Now. Again, it’s dull to blame Williams for his pretensions or blunt statements when The Human Surge‘s overall shape is so ungainly and strange. Even if ostensibly about the millennial generation, its emotional pathos is absent; we’re not necessarily taking part in a victim narrative regarding youth in impoverished countries with their lack of opportunities.

In progressing towards an ending that seems like an indication of technology coming closer to attaining human life, Williams is perhaps issuing a threat or maybe even a note of optimism. Regardless, his attitude seems unchanged.

The Human Surge premiered at the 2016 Locarno Film Festival and will be released on March 2.