Long past the days of the booming Hammer Horror industry, the contemporary British genre cinema, while still able to churn out the occasional 28 Days Later or Attack the Block-esque international breakthrough, seems to more often revel in the niche (a.k.a. openly juvenile), if not particularly original, ’80s throwbacks of, say, a Neil Marshall. In other words: it doesn’t often look to the future as much as it seems stuck in the past.

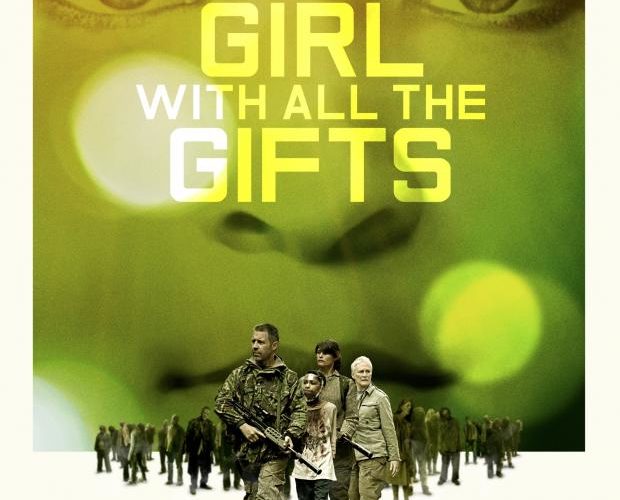

With the pedigree of a starry cast and acclaimed literary source material, it’s not unfair to read into The Girl with All the Gifts as the hope for the nation’s next great intellectual (read: allegorical) horror film. Yet without the narrative or formal conviction to pull off the clichés rampant throughout, it sadly seems stuck between two worlds.

Beginning in the depressingly familiar sight of an underground military bunker, expectations rise with the entrance of a number of children locked into wheelchairs and restrictive headgear — maybe silly, but perhaps bringing hopes up of channelling a true, undervalued British horror classic, Joseph Losey’s These Are the Damned. Though soon after they’re revealed to be zombies, thus placing this film naturally in the dystopian young adult adaptation mold, expectations are set back at square one.

Our titular girl with all the gifts, Melanie (Sennia Nanua), is part of the group of children infected with this flesh-eating virus, yet still intellectually and emotionally beyond going about their day simply grunting and chasing food — not to mention clear of the scabby zombie make-up on the film’s undead. With a clear interest in Greek mythology and creative writing, her sensitive English teacher, Ms. Justineau (Gemma Arterton), takes a clear liking to her, and, in a wholly corny moment the film feels justified giving us between these two characters in its first ten minutes, lovingly touching her head in slow-motion. Though we almost immediately get a record-scratch when gruff military man Sgt. Parks (Paddy Considine) interrupts her tender moment, quickly reminding that these children are, in fact, still monsters. Holding court over both of them is stern scientist Dr. Caldwell (Glenn Close), who seeks a vaccine by studying the children’s selective immunity — thus attuned to their uniqueness, like Justineau, yet not above looking at them as detached as Parks does.

Though once there’s an attack on the compound (a surprisingly large-scale zombie swam that clearly used all the extras a BFI budget could afford), our unit hit the road and settle in a ravaged, abandoned urban landscape. The stakes start to reveal themselves as a possible complete apocalypse. While the film boasts one particularly clever image — hordes of zombies asleep while standing up — the various set-pieces unfortunately come replete with indifferent hand-held camerawork, only emphasizing the film’s self-seriousness and lack of imagination.

But overall it’s not sticking to Melanie’s perspective and instead feeling more compelled to focus on these three authority figures that is the film’s downfall. Each spout variations on the same dialogue: empathetic platitudes from Justine, belligerent one-liners from Parks, and mounds of exposition from Caldwell (Close, the clear pro she is among the cast, still manages to bring gravitas when monologuing about fungus or zombie-resistant gel). Ultimately, our monster child’s coming-of-age holds more interest than slamming together science-fiction babble with the drone of more gunfire.

At least the ending teases something akin to that of Richard Matheson’s I Am Legend, as well as a wholly better film: one where conflict has manifested into something wholly different than another fight for the future.

The Girl With All the Gifts premiered at the 2016 Locarno Film Festival and will be released on February 24.