The comparisons between The Zero Theorem and Terry Gilliam’s most-beloved film are inevitable: dystopian sci-fi, a looming corporation, one lone man navigating this future yet, hopelessly, a drone to the very end. But Terry Gilliam better damn well have a reason for blatantly positioning his newest as a return to Brazil. The issue at hand is that, ultimately, The Zero Theorem seems to have no justification for itself, despite the potential of a wealth of contemporary issues, whether it’s the technological overload of social media or its ensuing series of political contradictions. Of course, the ultimate irony of this film is that it revolves around the old thematic chestnut of pointless existence, yet ultimately finds little reason for its own.

Sad-sack hacker Qohen (Christoph Waltz), socially inept to the point of always referring to himself as “we,” is heavily isolated, but still a cog in the machine — specifically Management (Matt Damon in an owed-a-favor-extended cameo), who tasks him with searching for the titular zero theorem, itself the meaning of life. Mostly represented in his hacking activities as Tetris-like computer effects, this search becomes all the more complicated when two figures posit a challenge to his manhood and ultimate purpose: an intern (Lucas Hedges) and a call-girl (Mélanie Thierry). The former is about one-third his age and ready to replace him, while the latter proves his seeming asexuality a put-on with one glance at her in a skin-tight nurse’s outfit.

Yet when Qohen steps outside his home to walk amidst the future London — which, amongst the plethora of advertisements, shows Occupy Wall Street rebranded as a corporate slogan — it only evinces the film’s squandered potential. Gilliam’s more interested in interiors than exteriors, staying with the hacker in his large-yet-vacant headquarters — as well as the disappointingly unimaginative recesses of his mind — which seems representative of the film’s own problems: it stays locked-up within the Gilliam tropes without willing to explore the greater possibilities at hand.

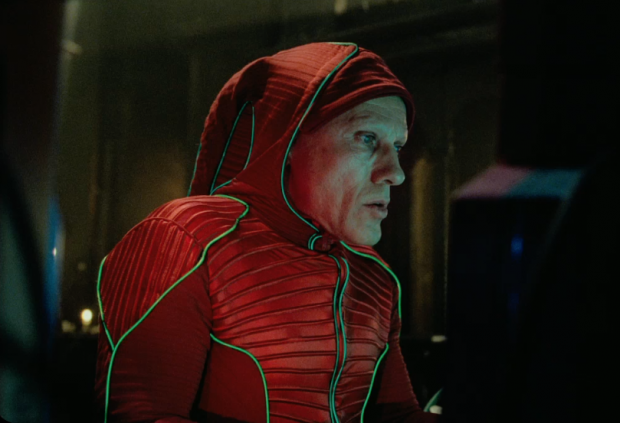

With this, even the director’s trademarks (canted angles, dwarves), which were always rote surrealism to begin with, come off as auto-pilot. A true case of familiarity breeding contempt, it becomes easier to see him spinning his wheels when all the tricks are laid out as just part of a rigid formula. Ultimately, for a film trying to break free from the conformity of both its own universe and Hollywood, it comes across as awfully tired — and, furthermore, Theorem reaches awful tackiness when its costume design can make one actually feel embarrassed for Peter Stormare.

Likely the only real absurdist energy in the film emerges from Waltz and Thierry’s various interactions, in which their clashing European accents give the impression of its own globalized science-fiction world. Unfortunately, the teen hacker (who’s tone-deaf performance can’t really be excused by the character’s age) only pushes the film’s commentary towards Gilliam’s cranky-old-man public persona.

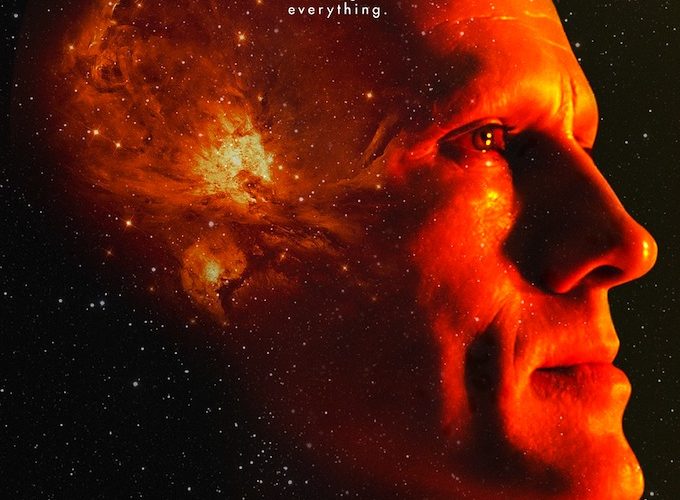

Though it’s to the film’s credit that it at least wears the artificiality of its numerous low-budget digital effects on its sleeve, thus blatantly shunning the wannabe verisimilitude of industrial blockbusters. This is at least one indication of Gilliam using 21st-century filmmaking to his advantage, yet it still doesn’t form or lend to an overall thesis of any magnitude, as even its most striking image, the bookending appearances of an enormous black hole, represents the overall experience: an overwhelming mass of nothingness.

The Zero Theorem is screening at Fantasia Film Festival and will hit theaters on September 19th.