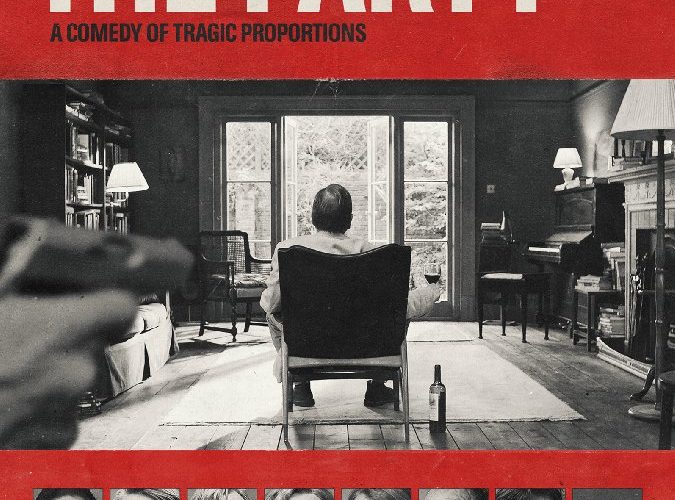

Liberalism will eat itself! At least according to The Party, that is, and we’re not just speaking figuratively. Indeed, at one point in Sally Potter’s new film — a riotous, if undeniably stagey black-and-white mid-length feature — a central character (played by Kristen Scott Thomas) decides, however subconsciously, to chew her own arm instead of sensibly taking out her anger on her unfaithful husband. “But I don’t believe in revenge,” she cries out. You can tell even she is having a hard time believing it. This poor soul — the main host of the titular gathering – – has just learned that her husband, Bill (Timothy Spall), is not only dying of cancer, but has chosen to live out his remaining days with the younger woman with whom he has been having an affair for the previous two years.

The character’s name is Janet and the party is intended to be a celebration for her, having just been given the position of shadow health minister for an unnamed UK opposition political party, a job we learn she has been working towards for years. Also present are Janet’s friend, April (a knock-out Patricia Clarkson, with a black dress as sharp as her tongue); her new-age hippy boyfriend — and butt of all her best jokes — Gottfried (Bruno Ganz); Bill’s old university friend, Martha (Cherry Jones), and her wife, Jinny (Emily Mortimer), who has just learned she is pregnant with triplets; and, last but not least, a coked-up Irish Canary Wharf banker named Tom (Cillian Murphy) who is carrying Chekhov’s literal gun. Tom’s out for Bill’s head, we soon learn, and flips a lid when he hears that the old man’s body might beat him to it.

It’s an interesting and apparently ubiquitous theatrical setup these days, and one we’ve seen more than a few times on screen, as in the Dogme film Festen or Carnage from Polanski: take a group of worked-up charlatans, place them in a confined space, and light the fuse. What The Party can lord over those films, however, is a bona-fide straight shooter. Clarkson’s arsenal of cynical put-downs are not only the funniest thing about The Party by a distance; she also seems to hold the whole shambles together. The woman simply will not suffer fools and, luckily for the audience, Potter’s film is teaming with them. “You’re a first-class lesbian and a second-class thinker” she snaps at Cherry Jones’ professor for gender-something-or-other. Potter knows she has a secret weapon in Clarkson and she’ll be damned if she lets her run out of ammunition.

For being shot in the month when the UK voted to leave the EU, it’s difficult to watch The Party without drawing connections to Britain’s current political landscape: the docile opposition to the Tory government’s hold on power; the gung-ho financial district creeps; the infighting, rudderless Labour party. Liberals eating themselves indeed. It’s Potter’s first film with cinematographer Aleksei Rodionov since they worked together on the director’s breakout Orlando back in 1992, but you really wouldn’t know it. Far away from Orlando’s lush period décor, Rodionov shoots it black-and-white that’s heavily lit from above, apparently with the intention of disorientating the viewer and bringing out — in high definition — the years of wear and tear on the faces we see on screen.

We shouldn’t compare, but still it might come as a disappointment if you (like I) have gradually come to know Sally Potter as an aesthetically gorgeous and visually inventive filmmaker. Moreover, it speaks to a general meekness surrounding this production, especially when considering it as the follow-up to Ginger and Rosa. (Not a masterpiece, I would argue, but her only other film this decade, and one that was a return to form for Potter in both artistic and box-office terms.) We might be wrong to expect more, since she’s never been the most consistent of filmmakers. To paraphrase Llewelyn Moss: if it ain’t Sally Potter’s next great film, it’ll do until it gets here.

The Party premiered at Berlin Film Festival and opens on February 16.