One does not necessarily have to be fond of canines in order to love Isle of Dogs, but it helps. It may also help to have a fondness for the meticulous craft of stop-motion animation itself or, even more interestingly perhaps, for Japanese cinema. It is a delightful, exquisitely-detailed production that sees Wes Anderson return to animated filmmaking for the first time since Fantastic Mr. Fox, and it’s clear, as he has admitted, that his biggest influences were not the works of Laika or Aardman, but rather Akira Kurosawa.

Any fan of that Japanese master’s work will surely clock that reverence (and smugly pat themselves on the back) as soon as they hear the first rumble of Alexandre Desplat’s thrilling Taiko drum score. The first such visual queue only comes after the film’s busy prologue is completed when, framed in front of a minimal white horizon, four silhouettes appear. However this time it’s not wandering samurai we spot in the distance, but four dogs scavenging for food.

We’re on Trash Island, a precarious looking heap of rubbish cubes that could have been assembled by one of the compacting robots in Wall-E. It’s 20 years in the future and the cat-worshipping Kobayashi regime that rules the fictional dystopia of Megasaki has decreed to deport the city’s dog population (migration allegory klaxon) for fears that humans will be contaminated with a newly discovered Canine Flu (fake news klaxon). The world created is one of magnificent texture. Fights take place amidst a cloud of cotton wool; television feeds appear as 2D cartoons; and a countless multitude of wiry hairs move with pleasing unpredictability. This is animation at its most tactile, it’s as if you could reach out and feel it.

Our hero is a 12-year-old orphaned boy named Atari (voiced by Koyu Rankin) who we first meet after he crash lands on the island while attempting to find his own lost pooch, a guard dog named Spot. Atari is moxie incarnate, all slick shiny overalls, slingshot at his back, the kind of kid who’ll pull a piece of shrapnel from his own cranium if he feels he has to.

The roving canines agree to help our young hero with his efforts and, in an interesting move–largely played for laughs, it seems, but with an edge of poignancy–Anderson has the dogs all communicate through English while Atari and his fellow Japanese humans all speak in their native tongue. No subtitles are offered, only the occasional translations of interpreters on screen.

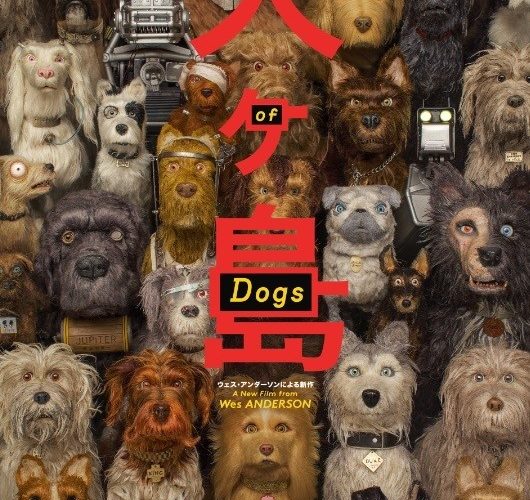

Impressed by their newfound friend, the dogs agree to help him in his rescue attempt and so Anderson–ever the fan of a good rag-tag gang–lines up the troops. We meet Boss (Bill Murray), the ex-mascot of a professional baseball team; Rex (Ed Norton), a loyal but domesticated beast; King (Bob Balaban), a dog who once was the face of a famous treat; and Chief (Bryan Cranston), the only stray, a lone wolf character who admits to occasionally biting and always refuses to sit. Chief’s story is at the heart of Anderson’s film and the animal’s unwillingness to accept subordination proves to be its most endearing theme.

The plot expands with reliable fluency, but such is the inventiveness, subtle homage, and kinetic drive of these opening two-thirds that it is unfortunate to see Isle of Dogs slip into an almost monotone sentimentality for its final act (I lost count of exactly how many characters welled up on screen). In place of that satisfying whole, however, it is still entirely pleasurable to once again get lost in Anderson’s signature wash of exquisite detail. I still can’t shake the image of a stop-frame kidney transplant shot from above or the fluid movement of two clay hands as they construct the perfect piece of poisoned sushi. The enduring filmmaker’s style may have its detractors but there is still nothing quite like it in contemporary cinema.

Isle of Dogs premiered at the Berlin International Film Festival and opens on March 23.