In Romania at the end of the 1980’s–the autumn years of the Ceausescu regime–Adrian Porumboiu worked as a professional referee for the national football league (or however it was referred to at the time). His son Corneliu (born in 1975) would grow up to become a significant filmmaker in the so-called Romanian New Wave of the mid ’00s. In 2014, Corneliu made a movie about his dad called The Second Game in which he narrated over a full 90-minute match that his father had refereed. Through the ever-politicized veil of sport the director was able to talk about the realities of those times. He returns to the beautiful game in 2018 with Infinite Football, a contemporary portrait of a man who suffered a bad injury before his career—at least in his eyes–had the chance to take off.

The man in question is Laurențiu Ginghină, a close friend of the filmmaker who now spends his days working in some sort of government administrational position. We’re first introduced to Laurențiu on the pitch where he used to play as a young man and where the fateful injury happened. How promising a talent Laurențiu was is never quite made clear but what is clear is the fundamental grudge he has held with the game ever since, or at least with its current form. As a result of all this—and here is the rub—Laurențiu naively hopes to change the structures and rules that govern the most popular sport on earth.

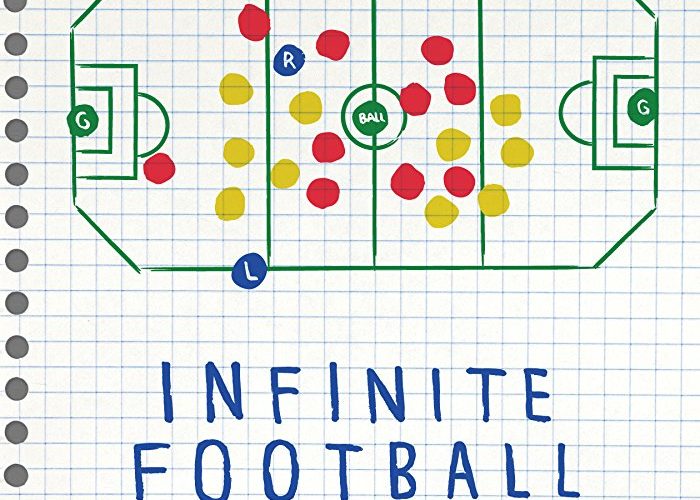

The concept, indeed, is laughable and would have come off a quite stodgy stuff in a less witty director’s hands. Having suffered his injury as a result of being backed into a corner, Laurențiu’s first decree would be to round off the corners, so to speak, and turn the rectangular pitch into an elongated octagonal shape. Next up is to split the surface into four zones and then to split the teams into increasingly elaborate subgroups. Laurențiu says that by limiting the players’ movements he will not only protect them but also liberate the ball to run free. Needless to say, or maybe not, the director finds plenty of existential things to consider behind that peculiar façade.

This was never going to be an easy sell, even if the film comes in at just over an hour. Porumboiu manages to keep things interesting by maintaining a light comedic touch and Laurențiu, in his wide-eyed sincerity, is more than happy to play his part. He speaks about his double role as a button pusher by day/sport revolutionary by night as if he were a comic book superhero with a double identity. He often goes off on wild tangents, referencing Heidegger and religious text, only to bring it all back to his mad rule changes in the most frank manner imaginable.

One of the most fascinating things about Infinite Football is that Porumboiu never feels the need to feed his pal any rope in order to get these moments on camera. The two men are close and the director pointedly takes the time to let us in on his friend’s life. During an interview in Laurențiu’s office–the sort of bureaucratic setting that wouldn’t look out of place in a number of Romanian New Wave films, not least Porumboiu’s own—the director uses a remarkable amount of screen time to show an encounter with an elderly local woman who has been waiting since the revolution to reclaim her land. Laurențiu ships her off to another office (we’ve all been there) and comes out of the situation looking somewhat inept, perhaps, but still like a decent guy. We even meet his father who presents Porumboiu with a print of a photo he took from the director’s wedding.

Documentaries are exploitative by nature and—without giving too much away–it is thanks to the friendship between these two that their wavelengths ultimately meet here, allowing this dense piece of filmmaking to come to such a satisfying denouement.

Infinite Football premiered at the Berlin International Film Festival and opens on November 9.