“Man is a wolf to his fellow man,” quotes a character early in Sergei Loznitsa’s A Gentle Creature. The ordeal suffered by its protagonist will indeed be solitary, poor, nasty, and brutish – it won’t be short, however. Powerful though bloated, A Gentle Creature is a companion to Loznitsa’s phenomenal first narrative feature, My Joy, once again following a person’s nightmarish odyssey through an allegorical rendition of post-Communist Russia. Though not as successful as its predecessor, Loznitsa’s latest nonetheless confirms the director’s place of honor amongst cinema’s most vociferous critics of Putin’s kingdom.

A Gentle Creature might borrow its title from a short story by Dostoevsky, but the relation between the two is even less apparent than between Loznitsa’s last outing, Austerlitz, and the W.G. Sebald novel of the same name. A much more obvious literary influence is Kafka. In lieu of an impenetrable castle, the film features a prison, to which the unnamed protagonist (Vasilina Makovtseva, whose character is identified as the title’s gentle creature and will be referred to as GC from here on), travels in the hope of delivering a parcel of groceries for her husband who’s locked up inside. His official crime is murder, but GC maintains that he was incarcerated for no reason. As one character states, everyone in this world will at one point be locked up without knowing why.

Upon arriving at the prison, GC is brusquely told that delivering the parcel isn’t allowed. When she asks for an explanation, the woman at the counter simply slams her window’s shutter down in front of GC’s face. The rest of the film charts GC’s impossible endeavor to somehow get the prison to accept her parcel. She knocks on many doors, and although several variously shady characters claim to be able to assist her, all that she manages to achieve is wasting money on help that never materializes.

The world GC is made to roam is lawless and hopelessly corrupt, like a contemporary version of the Wild West — people are perpetually drunk and shouting and ripping each other off. Brawls erupt on every corner, gangsters openly pimp out prostitutes, and the authorities are just as implicated as everyone else. Loznitsa, reunited with the exceptional DP Oleg Mutu (who also shot most of the Romanian New Wave’s masterpieces), captures this Hobbesian state of nature in very long takes, with the camera in the middle of the action so that the widescreen frame is teeming with figures and bustling activity. It makes for a relentless and claustrophobic viewing experience, like being cast into the middle of a Bosch painting with no hope of escape.

Were it not for the redundant dream sequence that takes up A Gentle Creature’s final half-hour and completely derails the film, Loznitsa may well have pulled off a masterpiece — if a supremely unpleasant one at that. It’s not clear what he hopes to achieve with this violently discordant shift into fantasy other than underline the narrative’s allegorical thrust, which was already plainly evident. The impression is that, stumped by how to draw GC’s travails to a close, he decided to go for broke. The wager doesn’t pay off. Since the film’s whole point is that there can be no resolution, perhaps Loznitsa should have taken another cue from Kafka and just left his story unfinished, breaking off mid-sentence.

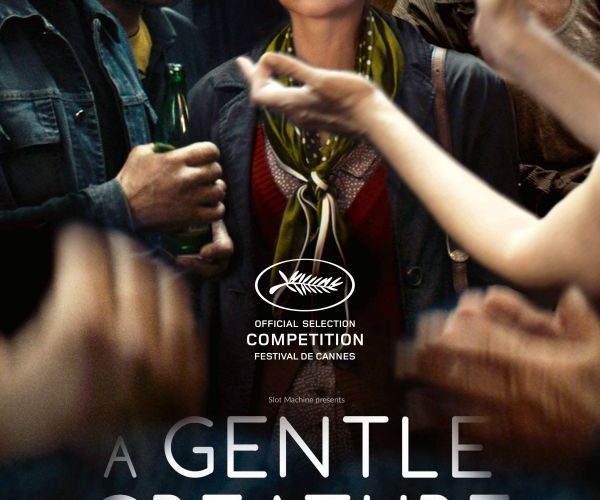

A Gentle Creature premiered at the Cannes Film Festival. See our coverage below.