Cinema lost one of its pre-eminent pioneers when Abbas Kiarostami died on July 4, 2016. Over the course of his 46-year filmmaking career, the Iranian master never ceased to probe cinema’s ability to represent reality, finding ever new ways of destabilizing our gaze and compelling us to interrogate the images he put before us, as well as his own role in doing so. The final chapter in this extended experimentation is 24 Frames, which was as good as finished at the time of Kiarostami’s death and has now been released posthumously.

Originally, Kiarostami’s idea was to animate famous classical paintings, creating a collection of four-and-a-half-minute shorts that imagined what could have happened in the immediate run-up and aftermath of the instant immortalized by the painters, thus putting into perspective the artist’s decision to represent a specific slice of reality rather than any other. In the finished film, only the first of the 24 “frames” is a painting — Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s The Hunters in the Snow. The painting appears onscreen, and, after a second or two, smoke begins to rise from the chimney of the house in the middle distance; then a few of the painted birds start flying around; later, a dog walks into the picture, sniffs the ground, and takes a leak on a tree. Gradually, most of the picture comes alive, both visually and aurally, and then, once four-and-a-half minutes have elapsed, it all returns to a quiet standstill, giving way to the next frame.

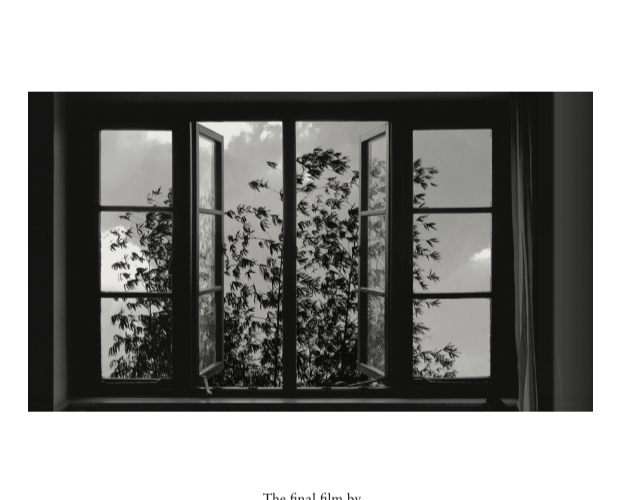

The remaining 23 frames are all photographs taken by Kiarostami — primarily of nature, which are animated and soundtracked in the same fashion, though there it’s never clear which instant corresponds to the original photograph. Alternating between color and black-and-white, the photographs feature a number of recurring interests and motifs. Many depict snowy landscapes in high-contrast monochrome, so that figures such as trees or animals stand out as silhouettes in the blinding whiteness. There are a lot of views of the sea taken from the shore. Windows are also frequent, creating a second frame within the frame from which to observe the scenery beyond. Animals, especially birds, appear in almost all the pictures (humans only come up in two), and snow and rainfall are near constants.

Although the animation effect is for the most part quite well-rendered and the animals are brought to life with impressive fluidity, there always remains a slightly jarring artificiality that prevents the viewer from fully sinking into the focused and contemplative spectatorship mode he’d intended. The result, it must be said, is also often quite tacky. When most of the picture is frozen except for snow falling in the foreground, for example, the image resembles a screensaver. More crucially, Kiarostami’s experiment defeats the very point of photography, as the photographer’s art lies precisely in capturing a specific instant that, on its own, has the power of evoking the life beyond. External elaboration isn’t simply redundant; it’s reductive, and it’s surprising that Kiarostami, an absolute master of the ellipsis, would curtail a photograph’s evocative potential in this manner.

Kiarostami’s exceptional talent as a filmmaker was devising formal experiments that helped him push further in his tireless enquiries into the human condition. That’s why when it came to his structuralist films, Homework and Ten were masterpieces, whereas Five paled in comparison to superficially similar works by the likes of Andy Warhol and James Benning. The same is true of 24 Frames, which, tragically, is not the swan song he deserves.

24 Frames premiered at the Cannes Film Festival and opens on February 2. See our coverage below.