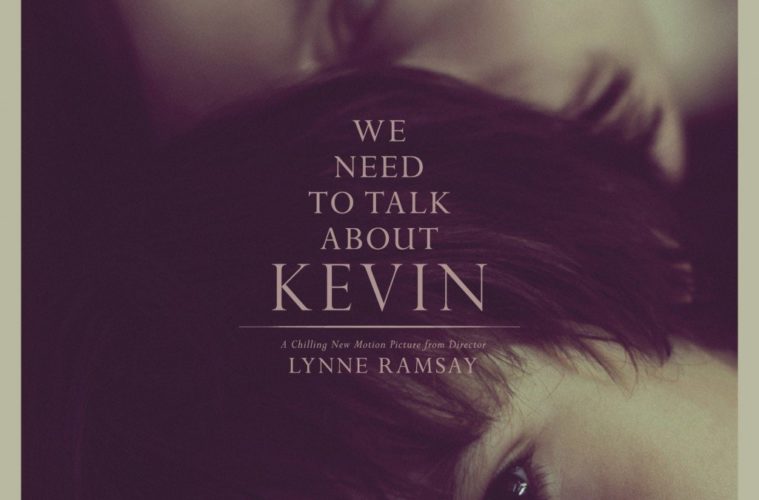

We Need to Talk About Kevin represents an immensely exciting piece of filmmaking from Lynne Ramsay (Ratcatcher, Morvern Callar). That might seem like an odd label for this adaptation of Lionel Shriver‘s best-selling novel, considering the relentlessly harrowing subject matter in question, but it’s hard to come up with any other phrase to describe the sheer vivacity of Ramsay‘s directorial approach. This is indeed a film that keeps your emotions in constant flux — terrorized by the actions of the titular character in one moment, happily floored by Ramsay’s consistently fresh choices the next.

It’s worth mentioning, too, that Ramsay, along with Rory Kinnear, wrote the film’s screenplay, which is a unique feat of adaptation in its own right. Like a few recent films — Sean Durkin‘s Martha Marcy May Marlene jumps immediately to mind — We Need to Talk About Kevin bleeds the past into the present, and vice versa, in a sickeningly effective attempt to force the viewer into the mindset of the protagonist — in this case, Eva Katchadourian (Tilda Swinton, in yet another nomination-worthy performance).

Eva is, at heart, an explorer, and back in the day she made her living in offices stocked to the brim with posters and maps that cover some of the world’s most magnetic cities. An early shot, captivating in its blatant obscurity, shows a deliriously joyful Eva being hoisted up by a group of people and splashed with tomatoes. In the next shot she’s shown spread out on a couch, lifeless, the exterior of her deteriorating house enveloped in blood-red paint.

What happens in between those two shots is delineated through various flashbacks that layout the timeline of Eva’s adult life, beginning with her marriage to Franklin (John C. Reilly). They have a young boy together, Kevin, who is played as a distant infant by Rocky Duer and as a six-to-eight-year-old ball of menace by Jasper Newell. Ezra Miller, who gave a similarly unsettling and worthy turn in this year’s Another Happy Day, takes on the role of Kevin in his teenage years, when his sick sense of humor is fully developed and his hostility towards his mother has become as clear as day (though not to the unaware Franklin).

In telling this nature-versus-nurture story, Ramsay puts an extreme amount of faith in her below-the-line contributors, each of whom ultimately enrich the film through their various outlets. Cinematographer Seamus McGarvey (Atonement) paints a canvas of perturbing images — whether it’s the blurring of focus in the Eva-Franklin memories or the skewed, claustrophobic framing of Kevin, the lenser is consistently amplifying the emotional and psychological dynamics at stake. Joe Bini, the frequent film editor of director Werner Herzog, excels here as well, coalescing Eva’s memories together into a field of heightened misery.

Ramsay also interweaves an eclectic and effective soundtrack into the film’s sensory landscape. Composer Jonny Greenwood (There Will Be Blood), doing solid work, isn’t given as much to do as one might have expected — Ramsay is more fond of inserting unexpected song choices, including Buddy Holly and Washington Phillips, in an attempt to materialize the distortion of Eva’s mental journey. Of all the sound work, however, most memorable is the way Ramsay very often exaggerates everyday noises — the crunching of cereal pieces, the water sprouting out of the backyard sprinkler — to terrifying effect.

The performances Ramsay evokes, too, are paramount in their impact. Swinton has been operating at an other-worldly level over the past couple of years, and she takes no step back here, giving a performance of perceptive fragility. Ramsay is often in such command that extended sequences go by without a shred of dialogue, and the expressivity — or lack thereof — of her lead actress speaks volumes. Reilly, meanwhile, is at home in a role like this, digging nicely into the skin of Franklin’s hands-off, laid-back demeanor. And the trio of performers saddled with the part of Kevin are all equally astounding. Miller will surely get the lion’s share of attention, and rightly so, as he plays the role in its fully-formed state, but the two youngsters are no less adept in their ability to communicate Kevin’s harboring savagery.

Many will come out of We Need to Talk About Kevin stunted by the punishing climax. But for me, that zenith of action was merely an enthralling cinematic event in a long line of them. Ramsay holds the tension at fever pitch from start to finish without ever diminishing the story’s emotional territory. It’s a truly stunning directorial achievement, one of the year’s most refined, and it’s in service of a narrative that’s light on redemption and heavy on disturbance. Hopefully more people will see the film than I suspect — it demands attention in the best possible way.

We Need to Talk About Kevin will open in limited release on January 13th and expand in the coming weeks.