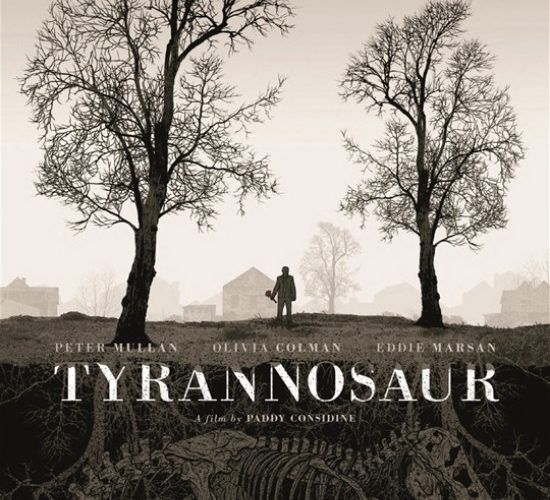

Paddy Considine‘s gripping directorial debut Tyrannosaur opens with a series of stark, brisk images that introduce the relentless destructiveness of the widowed, alcoholic loner Joseph (Peter Mullan). In one, he’s thrown into a fit by a couple of outspoken drinkers — Joseph is a frequent barhopper throughout the film — and deals with it by pummeling his dog to a merciless death. In another, he expels racial slurs at an Indian cashier (Archie Lal), and, after apologizing, finds a rock and launches it through the office’s storefront window.

It’s because of this that the sight of him entering Hannah’s (Olivia Colman) well-natured charity shop comes off as rattlingly incongruous. He quickly hides behind a rack of clothes, disappearing out of sight. Hanna tiptoes over, asks questions, and gets responses that aren’t helpful. However, being a friendly, devout Christian, she says a prayer for Joseph without even getting a good look at his weathered face. While this hasty acceptance is one of Hannah’s warmest qualities, it’s also probably the main reason why she finds herself binded in an abusive relationship with James (Eddie Marsan, fittingly despicable).

An unusual accord develops between Joseph and Hannah. He shows up at the shop on multiple occasions. She says a prayer for a friend of his who is on the verge of death. They discuss, often ruthlessly, the polarizing natures of their environments — his, a lower-class breeding ground for gang violence and brutality; hers, an upper-class subdivision of five-bedroom homes and lush lawns. It’s Joseph, at first, who commands the playing ground — ignorant of Hannah’s obscene spousal difficulties, Joseph thinks he’s seen the worst that life has to offer, and often tries to throw that belief in Hannah’s well-to-do, piously faithful face.

This is how much of the film’s first hour plays out — Joseph and Hannah trying to survive amidst their mutually horrific surroundings, while occasionally joining hands in moments of reserved intimacy. It works because of the quality of the acting, the quietly revealing dialogue, and Considine‘s steadfast, articulate direction. But it’s far from revelatory material. It isn’t until the film’s punishing third act that Considine‘s screenplay rises to the level of the performances and finally becomes something that starts to spiral in unexpected directions. Once the visceral impact of Considine‘s volatile depictions are matched by an corresponding emotional blow, the fireworks really begin to start.

Not enough can be said about the performances Considine draws out of his cast. Peter Mullan, who has an uncommonly expressive face to begin with (if his face doesn’t seethe with burning intensity, then I don’t know whose does), is able to soar with a character that comes to be defined by a frank, unapologetic view of his own destructive self. This isn’t a violent-man-meets-spiritual-woman-and-gets-redeemed performance — this person is a fiery savage, knows it, and still finds within himself an inability to resist the volume of vigorous magnitude that boils within him. That’s complexity.

Olivia Colman‘s Hannah is given just as many layers — maybe even more. The first image we see of her — tear-stricken eyes, yearning for Joseph’s forgiveness — is the embodiment of genuine innocence. Yet the character experiences numerous ebbs and flows during the film’s progression. And it’s a characterization whose grand journey is even more staggering and powerful upon reflection — it achieves the uncommon effect of both illuminating what’s come before, and amping up what is still to follow.

To be sure, Considine‘s intricate work on the page is the root of this portrait, but Colman‘s performance is designed with such overlapping fervor that what ensues takes on another dimension. She is so convincing it’s almost frightening, and let’s be thankful that Considine didn’t fall back on her ability — he gave her plenty of threads to draw on, and she takes every single one of them and runs with it. Even Eddie Marsan, who viewers of Mike Leigh‘s Happy-Go-Lucky will keenly recall (he’s also set to make an appearance in Steven Spielberg‘s upcoming War Horse), brings depth to his detestable character — he’s nine-tenths devilish, but there’s also a quiet one-tenth of bizarre, restrained confusion.

Tyrannosaur is a challenge. There’s no doubt about it. It is unflinching in its presentation of violence — baseball bats meeting bodies and skulls, ruthless hounds tearing at limbs and faces, a profanely unsettling man whose first on-screen gesture is peeing on his pretending-to-be-asleep wife. What’s admirable about the film, though, as well as Considine‘s approach, is that it doesn’t justify this sensory assault through simple redemption and a cheery conclusion. Instead, it does so through sheer complexity — through characters who are elaborate enough to deserve a film that’s longer than 91 minutes, and through performers that meet these roles head-on with a foaming desire to add layers at every step.

Tyrannosaur is currently playing theatrically in limited release.