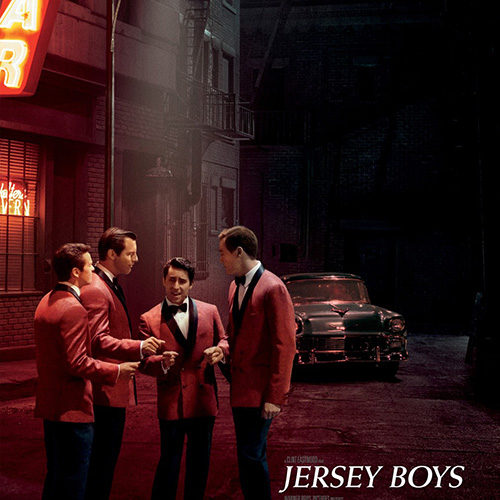

On the one hand, Clint Eastwood‘s stage-to-screen adaptation of Jersey Boys is an exercise in Broadway fidelity: rather than re-cast the project with established movie-star personalities, the director chose to fill out three of the four primary roles with actors who performed in the show’s original Broadway tour. Furthermore, according to an interview with Scott Foundas, Eastwood passed over a screenplay from veteran writer John Logan (Rango, Skyfall) in favor of a draft penned by Marshall Brickman and Rick Elice, who authored the original Broadway book. (Unlike Logan’s draft, Brickman and Elice’s script retains the fourth-wall-breaking gambit of the stage show.) On the other hand, Eastwood’s clear intention to abide by the stage show is undermined by the implementation of his late-period aesthetic, which sacrifices bright, bursting lights and concert-show spirit for musky rooms and cinematographer Tom Stern‘s arsenal of classical shadows, dusty greys, and deep browns.

The result is a film that, while perhaps underwhelming as a whole (and certainly something that won’t convert any latter-day Eastwood skeptics), still contains numerous pockets of interest. Consider, for instance, the wonderful fun Eastwood has toying with the various direct-to-camera addresses. At first, it appears that the actors’ sidebar narrations are conventional: tough-guy Tommy DeVito (Boardwalk Empire‘s Vincent Piazza), who is saddled with the majority of the fourth-wall responsibility, simply walks and talks to the audience, the camera tracking with him as he offers brief exposition and local New Jersey color. Eastwood replicates this set-up so methodically that, whenever a scene is introduced with a single character, we are triggered to expect a bit of transitional narration to occur. But Eastwood flips the trick on a number of occasions, as in a late scene, where a private rant by Frankie Valli (John Lloyd Young) suddenly turns into a two-person conversation when it’s revealed that his girlfriend (Erica Piccininni) is packing her suitcase in the next room. (A similar effect is achieved in an earlier scene that begins with Tommy combing his hair in front of a mirror.)

Eastwood’s decision to keep multiple actors from the Broadway tour is also revealing, considering the director’s well-known preference for quick, efficient shoots that rarely accommodate more than one or two takes per set-up. (“You’ve got people who’ve done 1,200 performances; how much better can you know a character?,” Eastwood states in the Foundas interview.) Needless to say, however, performing Jersey Boys on stage is radically different from performing it on a Clint Eastwood set, and though the Broadway holdovers—in addition to Young, there’s Erich Bergen (as songwriter Bob Gaudio) and Michael Lomenda (as bass player Nick Massi)—make good on their musical talent, they are altogether more stiff and uncomfortable when it comes down to the nuts-and-bolts of a dramatic conversation or altercation. This is especially true of Young, a 38-year-old man who, when the film begins in 1951 in Belleville, New Jersey, has practically no chance in the world of convincing us that he’s a 16-year-old kid who drinks milk with his spaghetti at the family dinner table. (Piazza, the lone Four Seasons player with no connection to the Broadway show, is by far the most charismatic and energetic of the principals.)

On a narrative level, the movie spends a lot of time setting up a framework of working-class New Jersey brotherhood before delving into the jukebox-musical structure that paves the way for renditions of “Sherry,” “Big Girls Don’t Cry,” etc. The downside of this choice is that, though the emotional dynamic among the four members is clear and promising—with Gaudio’s well-bred roots making him an intriguing outsider in the group—the narrative developments and rise-and-fall mood swings that populate the rest of the film are simply too demanding for Eastwood’s modest production scale to handle. Considering the amount of plot on display here—the movie begins in 1951, and ends in 1990 (with some shoddy old-age make-up that J. Edgar detractors will surely pounce on)—it’s insane to think that the production budget of Jersey Boys, at $40 million, is only $7 million more than Gran Torino‘s $33 million. (Similarly, Changeling—which, like Jersey Boys, is a period piece with about six plots squeezed into one movie—cost $55 million.) This out-of-whack relationship between subject matter and scale—the plots are getting bigger, while the budgets are staying relatively in the same ballpark—accounts for much of the uneven scene work that plagues Jersey Boys.

This is made clear most glaringly through the film’s female characters, starting with Frankie’s first wife, Mary (Renée Marino). It’s possible to portray a relationship like this with diligent, useful economy (especially in an ensemble picture that, by nature, requires such brevity), but here, with the relationship dubiously jumping from one interval to the next—first-date flirting, marriage, Mary’s alcoholism—it’s impossible to get a grip on how these characters relate to each other and what their relationship means. Frankie’s relationship with his troubled daughter suffers from a similar fault: at one point, she’s a background presence that barely even registers; at another, she’s suddenly one of the emotional cores of Frankie’s arc.

Even with these missteps noted, the movie is a pleasure to look at: Eastwood and production designer James J. Murakami‘s sense of place is phenomenal, from the shiny red booths of a diner to the paper-filled offices where Frankie and the Four Seasons duel over contract disputes and personal rivalries. (Two days removed from seeing the film, I still remember a cup of pencils sitting on a desk in one of those offices—even in scenes as short as that one, Eastwood populates the frame with small details and objects that are breaths of fresh air.) And there are moments, too, where Eastwood breaks out of his prestige-drama bubble and offers surprising spurts of energy: the closing-credits curtain-call; a speedy dash up the front of the Brill Building; numerous references to films of the day, from The Blob to Ace in the Hole; a “Hitchcock moment” where Eastwood appears on television as a character watches Rawhide; and, in what might be the film’s best scene, a humorous full shot of a room of men, each of them with a large glass of red wine, preparing to settle a debt in the mansion of a gangster (a delightful Christopher Walken).

Jersey Boys is now in theaters.