There is a lot to love about Jeff, Who Lives At Home, the newest film by the writing/directing team of Mark and Jay Duplass. I could (and intend to) go on for paragraphs about all of the merits of this film. However, the bulk of what I am about to say comes with one very real caveat: to enjoy this film, you must be able to exist on it’s level.

That is not to say that this film requires an adjustment of expectations. For my money, you could go into this movie influenced by all kinds of hype and still not be let down. What I mean is that Jeff, Who Lives At Home is a film that espouses an idea, and has a character who is an embodiment of that idea, and should you fail or refuse to at least acknowledge the internal logic behind that idea you are not likely to enjoy it to the extent which you should.

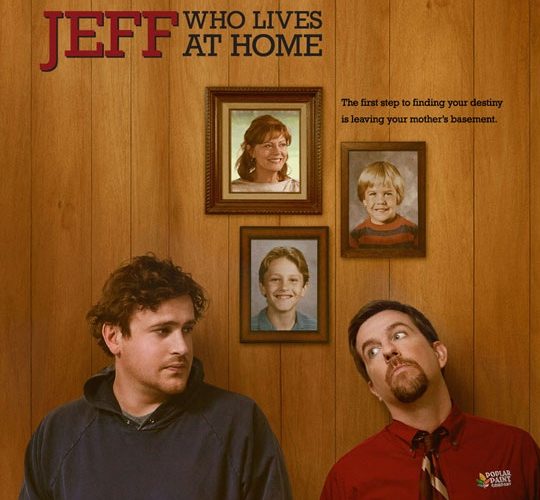

This is, after all, a movie with a protagonist who lives his life in a way that even a strict adherent to predestination might recognize as excessive. Jeff (Jason Segel) is in his thirties and lives in his mother’s basement, subsisting off of her charity as he waits for a sign from the universe to guide him in his life. When a suitably nebulous clue comes he strikes out into the world for seemingly the first time in ages, under the pretense of getting some wood glue for his mother (Susan Sarandon). At the same time, his brother Pat (Ed Helms) is having trouble engaging in his marriage, and deals with this growing rift by refusing to talk about it with his wife Linda (Judy Greer).

Each of these characters, including Sarandon as the beleaguered mother of these two men, are engaged in a sort of self-imposed inertia. They are stagnating in their lives in a way that is more tragic than dramatic, and is thus all the more relatable. These are people who are not so much unhappy as they are bewildered, content in their lives but stuck for an explanation as to how they got there. As such, they are held back from action due to their lack of understanding regarding how they got here in the first place, and are thus unwilling to risk further uncertainty.

The way in which Jeff deals with this is novel and beguiling. He begins to take signs at face value, following every thread in the hopes that it takes him where he needs to be. He begins a period of hyper-engagement which brings him into the slipstream of his brother, who is a cynical and un-empathetic borderline narcissist. Segal is the perfect choice for making Jeff’s childlike commitment to fate work, but Helms really shines in a role far from his usual troupe of naive-but-good-hearted dullards. He makes Pat instantly reproachable, but never unsympathetic.

The Duplass brothers also deserve credit for their accomplishment. They make characters that are so wholly realized and complete that they feel like old friends, which makes it much easier to laugh at them and still care deeply for them. Unlike many comedies, there are no moments of comedy here that come from a place of mean spirited reductiveness. It’s a rare and courageous choice, and it pays off in the movie’s later dramatic moments. That these moments contain the Duplass’s trademark gift for simple, humanist honesty in both dialogue and character is only further icing on this already decadent cake.

I’m sure there will be those who can’t get behind the almost sainted way in which Jeff is portrayed, and the manner in which the belief in fate playing a hand in events is communicated. But given that this film espouses the idea that for fate to work the subject of it’s design must take action, I find the whole story and moral to be at once beautifully simple and uncommonly enlightened. Maybe today is the best day, and maybe we will be led where we are supposed to be – but the final step is for us to do what we feel we must, and that moment of decision can only come from within.

Jeff, Who Lives At Home is an uplifting and often hilarious film that never mires itself in saccharine dishonestly, and should easily take place at the top of anyone’s list of favorite films for the year thus far.