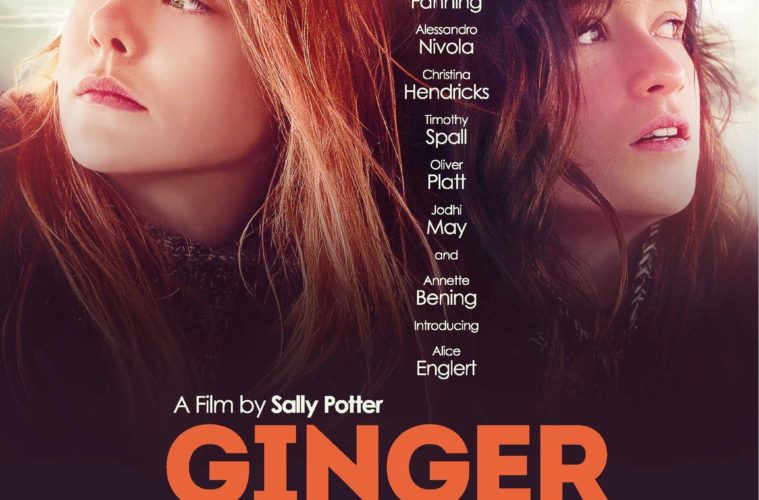

Director Sally Potter has carved out an intriguing niche in the filmmaking world. Her previous feature, Rage, premiered on mobile phones and her breakthrough Orlando remains a spectacle quite unlike any other in its bold art direction and manipulation of gender and history. But Ginger & Rosa is a step toward the mainstream, and not one that should have any fans worried. The sharp writing and visual flair still present themselves confidently, and tour de force acting makes this arguably her best work to date.

When one first meets the titular duo, Potter tells a lot without letting her characters utter a word. Their birth on adjoining hospital beds allows us to predict their tight friendship, the date’s alignment with Hiroshima immediately prepares us for the existential angst that the story will concern, and when we finally get to look at them 17 years later, that they wear the exact same outfits affirms their friendship while also suggesting a desire to fit in, at least with someone. Yet Ginger (Elle Fanning) stands out, her bright red hair contrasting with her surroundings, her clothing, and most of all, from Rosa (Alice Englert). Ginger does not fit in with her surroundings, and we are going to find out why.

Rosa’s father is absent, and neither girl like their mother, but Ginger has respect for her godfather’s and their friend May Bella (Annette Bening, in a small but memorable role) and speaks to them in a more open-minded manner. They are a mediating force, a place to allow Ginger a chance to vocalize but also test her understanding of the world. The major authority figure, however, is Ginger’s father, Roland (Alessandro Nivola). Roland’s matter-of-fact insistence that “God is an invention” and that Ginger’s crucifix is “a bit kitsch” set him up as the pretentious idol-figure that was used in Noah Baumbach’s similar The Squid and the Whale. Both girls idolize him, leading to a plot development that has become a cliché of the genre but remains moving in the deliberate pace and focus with which it unfolds.

Potter rarely insists on telling us anything, and her excellent composition and mise-en-scene allow for the T.S. Eliot book on Ginger’s nightstand to come back later, the details do all the talking. When the two girls begin to dress differently, we know that they are going to be at odds. Rosa is not as articulate or mature as Ginger, opting for Girl magazine, while Ginger reads the latest from her favorite existentialists. Rosa opts for Church and God’s grace, while Ginger continues to attend Ban The Bomb meetings, mouths off at her mother while Ginger allows mediation from her godfathers. But the girls are far from polar opposites, and while we get the sense that Ginger may be tagging along with Rosa to a party or smoking cigarettes because Ginger is, the bond is also clear. The two shrink their jeans together and hold small conversations fringing on feminism.

Indeed, gender roles are a major theme of Ginger & Rosa, as we are reminded more than once that Natalie (Christina Hendricks) gave birth to Ginger as a teenager and abandoned her painterly ambitions, and as Ginger insists that she is never going to have any babies and that her mom ought to get a job, it’s enlightening to see why she begins to paint again. This is a world where everything connects, where a conversation in one place will ring true several scenes later, or where mere reaction shots at a dinner table can remind us just how young Ginger is. Potter may be guilty of over-emphasizing, but she is certainly not guilty of any lies; this is one of the most realistic coming-of-age films to grace the screen in some time.

The writing is sharp throughout, prone to occasional redundancy but infinitely believable and terrifically paced. Every character (perhaps with the exception of Rosa) is likable but flawed, never symbolizing anything before focusing on personality, and Ginger’s dialogue in particular is a portrait of an ambitious and intelligent teenager, but a teenager nonetheless. She speaks confidently of good principles but takes them too far, and her poetry displays potential but not immediacy (those who have seen Yes know of Potter’s poetic skill and understanding), developing as the film goes on, giving the events a sense of time that nicely supplements the picture-perfect period detail.

Even when Potter does make too fine a point of something, her actors keep her safe. Rivola is particularly convincing in a pivotal role. He should come off as pretentious, but his insistence on “autonomous thought” and other ideals that he was jailed for work thanks to well-mannered body language and awareness of tone and pacing. The consequences then, to himself and to both girls, paradoxically feel outrageous but entirely normal, as if a good upbringing went bad for no reason at all. Hendricks, too, fleshes out a slightly underdeveloped character to make her a crucial figure in the film’s feminist plight and the shifting sense of morality and purpose in the ‘60s. Fanning, however, is a revelation, giving not only her best performance to date, but what will certainly hold up as one of the year’s best performances. She is at turns passionate, devastated, helpless, and cocky, creating a fluid image and delivering every line with the appropriate level of dignity and grace.

What emerges transcends the simplistic label of an existential coming-of-age story and becomes a charged character study with thematic richness regarding youth, feminism, war and perhaps homosexuality. It’s rare for such a focused film to be able to articulately comment on a wide-range of topics. That Potter uses period details to instill relevancy makes it even more impressive, but Ginger & Rosa is a rare film in many ways, a poignant and insightful one whose wide grasp is never overreached and says as much in what it doesn’t say as what it does.

Ginger & Rosa is now in limited release.