In cinema, differentiating it from most other mediums, one has the ability to give life to drama: time to flesh out characters, fill an unfolding story with intricate details, and capture it in a way that is enthralling to the eyes. Free State of Jones, written and directed by Gary Ross, clearly has a fascinating historical figure at its center and a story that is unlike a multitude of other Civil War era dramas, yet it too often feels (quite literally, in some cases) that we’re retreading the bullet-point notes from a fourth-grade homework assignment rather than experiencing an emotionally rousing, visually distinct journey.

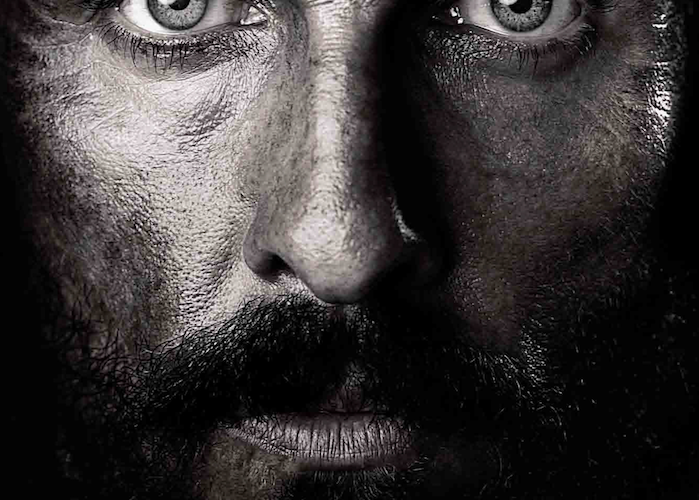

From the get-go, it’s quite easy to tell what attracted the The Hunger Games and Pleasantville director to the material in the first place. In the early-to-mid-1860s, Newton Knight broke free from the Confederate army to form his own company of “deserters,” women, and escaped slaves. In a guerilla effort to stick to their ideals and protect human dignity, together they created the “Free State of Jones,” an area in his Southern county of Mississippi which finds itself at odds with both sides of the war. Portrayed here by Matthew McConaughey, he has the fierce passion and necessary Southern drawl to convince both a single person and an entire crowd that the fight for not just freedom, but equality, is worth dying for.

As we shamefully know today, the abolition of slavery did not eliminate prejudice, and Ross ambitiously attempts to continue the story by going to Knight and company’s fight in the Reconstruction and far beyond; inelegantly spliced throughout the main narrative is the 1940s-set story of Knight’s mixed-race great-grandson Davis, who was caught in a legal battle for marrying a white woman. It has the makings for an entire season (or two) of a TV series — its drearily un-cinematic aesthetic certainly fits — but there’s little affirmation that many would tune in if it all came from the hands of Ross.

Told in the broadest strokes imaginable, even actors with a distinct presence such as Gugu Mbatha-Raw (playing Knight’s future spouse Rachel) and Maherashala Ali (as Moses, a key leader in Knight’s company) come across like poorly defined footnotes. Scene after a scene, it’s disappointing that Knight’s nobility becomes the forefront over the plight of those considered less-than-human by half the country. When he gives a gift to Rachel or clings to the feet of a friend who was lynched, it’s framed more as an emotional catharsis for him than anything else. The group Knight leads is facing certain death at every turn, but little agency is given to what’s an inherently complex decision. The plot, relayed in a dull cyclical manner, features approaching danger; Knight gives a rousing speech or makes righteous remarks to an individual as he hatches a plan; reminders of the despicable acts of slavery are inserted when a jolt is needed.

As we abruptly transition to the Reconstruction, what was once a languid drama turns even more into an checklist of isolated historical events, but considering the relative lack of representation on screen, it’s slightly more compelling than what came before. We see the foundation of systemic injustice, most distressingly in a political sense, as a form of slavery is re-introduced legally and voting is corrupted. Even though it’s overrun with the kind of archival photography usually reserved for a end credits sequence — don’t worry, it shows up there, too — the sprawling aspiration to try and convey this much of the story is appreciated.

Ross does convincingly nail the brutality of the period — the first shot of war we see involves a bullet ripping through a skull, and it only gets more gruesome from there — but he fails to convey the emotion. Benoît Delhomme‘s cinematography consists of uniformly bland medium close-up shots with little sense of depth. As a stronger example of how it all seems like a pale imitation of what’s come before, for one of its most dramatic moments, it straight-up uses “What Must Be Done” from Nick Cave and Warren Ellis’ beautiful The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford score. Missing the aforementioned narrative intricacies so necessary for one to get involved — let alone stay awake — Free State of Jones has a story worth telling, it just doesn’t know how to effectively do so.

Free State of Jones opens in wide release on Friday, June 24.