Based on Fatima Elayoubi’s book, Prayer to the Moon, Phillipe Faucon’s Fatima is a slice of immigrant life story that’s become increasingly familiar as filmmakers have examined the generational divide in family structures. But while Faucon’s film treads over many of the same thematic conversations of films ranging from The Namesake to La Promesse, it nonetheless offers an impressively empathetic understanding of three very different generations.

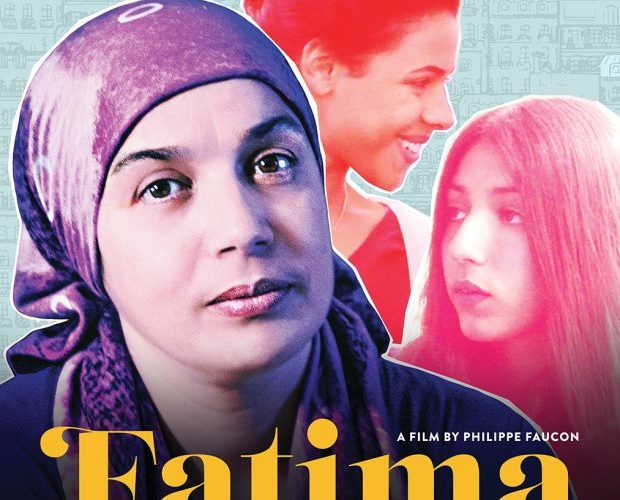

Fatima (Soria Zeroual) is a resolutely traditional Muslim woman who feels out of sync with the values and basic characteristics of France – even as she emigrated decades earlier from Algeria. Divorced from her husband, Fatima works herself to death trying to provide for her two daughters – Nesrine (Zita Hanrot) and Souad (Kenza Noah Aïche) who view the world in vastly different ways than her.

Souad is a high-schooler who actively rebels against the expectations of Muslim women. She’s both ashamed of her mother’s position in life — “She’s a living rag,” she yells to her modernized father (Chawki Amari) in frustration late in the film — and deeply afraid that her future will resemble her mother’s. Spending most of her life in France, she has very little allegiance to her Islamic heritage, and isn’t afraid to stand up to a bullying teacher, or burp in front of a pair of lecherous men.

Nesrine, meanwhile, is a first year med student who’s agonizing over her impending exams, and feeling the weight of her identity and the expectations of her future. She’s furthest in a middle-ground between her Algerian and French identities, as shown in her desires to have a non-Muslim boyfriend, but also her inability to let herself indulge in even a single bag of sweets at the grocery store. She’s in a context that she never asked for, but feels obligated to respect.

Faucon’s filmmaking finds elegant ways to show these contrasting worldviews, even drawing parallels in the ways the parents react to each daughter having new men in their life. Fatima hasn’t even met Souad’s boyfriend, but she judges him as soon as she hears his last name, based on the fact that she knows his mother was a bartender. On the other hand, Nesrine is so conditioned to expect scrutiny that she’s surprised when her father wants to meet her new boyfriend – not to see whether he’s Muslim or has a nice family – but rather, to see whether he’s good enough for his daughter.

Like this year’s earlier Mountains May Depart, Fatima explicitly foregrounds the language differences between generations. Fatima is been in France for decades, but she’s still struggling with the French language, while Souad, can’t be bothered with the Arabic language. She finds it both unnecessary, and views it as an artifact that doesn’t affect her. That’s not to mention that’s she’s already the target of Islamophobia for the color of her skin.

Faucon is smart enough to not just make this a story about forced cultural obsolescence. The film instead offers continual continual visual and spoken conversations about the duality of meaning in language, and the character’s contrasting philosophies. Where Fatima worries about the immodesty of Souad’s clothing, she’s more worried about being hot in the weather.

Faucon has a gentle touch in showing these differences, but the dialogue too often feels like an unnecessary explication. In one scene, Fatima listens quietly and intently to a parent teacher’s conference with clear discomfort as the other parents responds to the teacher’s comments before she’s finished talking. It’s a powerful enough scene, but Fatima proceeds to explain in detail how she didn’t understand why this was happening. There’s multiple cinematic patterns of showing and telling.

The ultimate problem with these scenarios is that they rarely feel like they add up to a complete film. At an hour and fifteen minutes, Fatima just needs something else whether it’s another subplot or a way for the central conflict to further bloom. A late-film incident seems like it’s going to start a whole new storyline about Fatima’s character, but it ends up being a bizarre piece of padding – even as the incident has effects that last months in the character’s life.

Fatima inevitably falls into a catch-22: every time it presents an insightful new cultural situation, it starts to feel less like a film, and more like a series of richly detailed sketches.

Fatima is now in limited release.