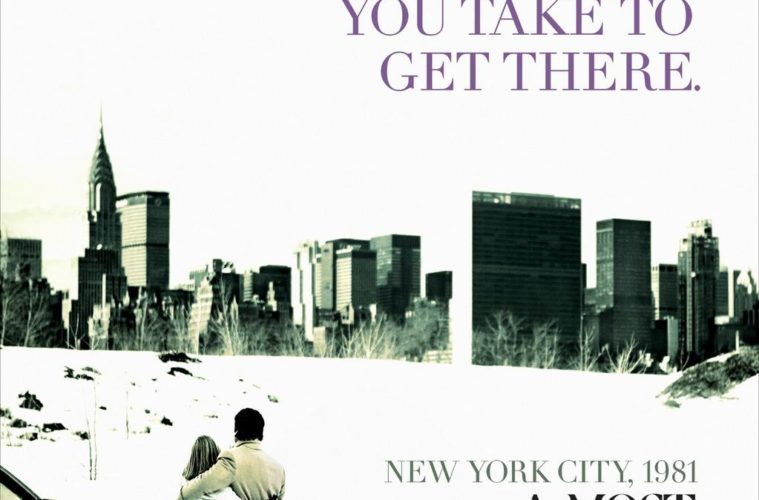

J.C. Chandor’s A Most Violent Year starts out on just the right moody note for a searing, low-level crime drama; a young oil truck driver is waylaid by thugs who beat him, drag him from his vehicle, leaving him with a broken jaw. The year is 1981, the setting is Brooklyn, New York, the man is Julian (Elyes Gabel) and this is not his story, but that of his employer, Abel Morales (Oscar Isaac). Set against a breathtakingly captured late 70’s/early 80’s cityscape, and beautifully acted by the likes of Isaac and his luminous-yet-cagey co-star Jessica Chastain, Year immediately draws us into an unlikely criminal underbelly; the cut-throat world of the heating oil business.

Chandor has a definitive knack for peeling back the fastidious daily processes that capture his characters in their clutches; in Margin Call investment bankers came crashing down upon one another as the market did the same, while the indeterminable exile of Robert Redford on his sea-stranded yacht grounded the fascinating All Is Lost. Here, he hones in on one element of New York City criminal life that, at first glance, seems mundane compared to, say, The Godfather, one of the film’s obvious inspirations. Yet, as the mild-mannered and initially honest Morales strives to take a crooked business he inherited from his father-in-law and ride it to success on the straight and narrow, the scenario reveals itself as one fraught with the usual mob-connected pitfalls, potent danger, and inevitable moral compromise. The stage is set with impeccable detail and grace, but the follow-through lacks the hot-blooded, take-no-prisoners attitude that the title implies.

It’s almost a genuine shock to find that A Most Violent Year doesn’t fully deliver; the immersive atmosphere, aesthetics and set-up are so potent that they seem destined to produce something genuinely special. The material is there to be mined, and there’s a declarative richness to much of the acting, even if the script that ignites it feels liberally borrowed from other sources. The film’s heart and soul lives in Morales, and Isaac continues an exceptionally strong acting streak, following up his work in Inside Llewyn Davis and The Two Faces of January, giving this would-be honest man a plausible sensitivity that’s actively tested by both his spiraling circumstances and the ethical dichotomy that forms his relationship with wife Anna (Chastain).

Chastain is mesmerizing to watch here, as usual, but her character never quite leaps to plausible life; instead, Anna mostly serves as a tricky plot point that destabilizes the fragile ground upon which Abel dares to tread. She’s a go-getter that has been struggling every bit as long as her husband to make this business work, but she’s also not beyond adopting some of her crime-boss father’s shady practices. At one point Abel strikes a deer with his car, and lacking the nerve to finish it off, is surprised by his wife brandishing a weapon and taking care of the job. Chastain establishes a fearless devotion in this doting and pragmatic woman, but there’s haziness around Anna’s edges, and although Year flirts with being the tale of a marriage under fire, it never fully explores that aspect enough to rise above surface level observations.

Detail and commitment to the world it lives is in is never a problem for A Most Violent Year, and the film’s most entertaining component is the way it orchestrates the wheeling and dealings of these heating oil honchos so they feel real, immediate, and shockingly dangerous. Chandor digs down deep within the setting and tears out the inner workings so he might reconfigure his characters to match their social habitats. The way Abel carries himself when meeting his compromised but curious lawyer (Albert Brooks in an inspired and off-beat turn) tells one story, while his earnest interactions with a DA who’s trying to nail Morales and his business to the wall, tell another. At some level, both aspects play into the image of the man Abel wants to become, but in trying to discern how best to combat the dirty tactics and menacing actions of his competitors, there’s another facet that threatens to stir to life. Visually, cinematographer Bradford Young evokes the dark and frosty undercurrents of this moral quagmire, and the city we are looking often feels less like a purely realistic rendering, and more the version of itself that sits in Abel’s conflicted heart. Melding the acting and the visuals is a wild, restless score by Alex Ebert that reconciles the film’s competing identities well.

I have now found my way back to that hapless driver Julian, at the film’s start. He’s a minor character, but has a pivotal function in the thematic framework; he’s employed by Morales and shares the same hopes and aspirations, but no matter how much he feels they are alike, nothing comes together for Julian in the same way it has for Abel. He’s a compelling and potentially fascinating counter-argument, but the film never truly allows him to emerge as his own identity. It’s frustrating to watch Year begin to build him organically into the story, only to eventually toss him out in a manner that questions his inclusion to begin with. Several character histories and side stories are treated in a similarly reckless manner, and instead of well-crafted ambiguity lurking at the film’s borders, we are left with inconsistencies in the storytelling, mashed down by some unnecessary heavy-handedness on Chandor’s part in the last third.

While it may not fully reach the heights of its potential, A Most Violent Year is still quite entertaining, and due to the level of artistic craft on display, it’s always a pleasure to watch. I personally found Chandor’s embrace of silence and internal struggle in All Is Lost preferable to the more cluttered drama on display here. Ultimately, Year still signals growth for the director, who has established that he can juggle a film with so many ambitious and unpredictable pieces and still find a measure of truth hiding there in the tangle.

A Most Violent Year opens in limited release on December 31st.