Has Mike Mills ever been unsympathetic to another human being? If his two most recent features, Beginners and this year’s NYFF centerpiece selection, 20th Century Women, were the only available evidence, one might be inclined to think not. Overused and a catch-all though it may be, “humanist” is a label that’s earned rather emphatically — not for expressing interest in people, but by mining into what makes that person. Those who they love, what they hold onto or spiritually, the things they own, what they’ve experienced, and, most important of all, how they process time cannot here be taken for granted in the slightest bit. Both films comprising this philosophy initially strike this writer as unbearable, readily digestible existentialism for dummies; and then they continue along a well-planned path until the material is less of a drama than a hyper-perceptive communication of experience.

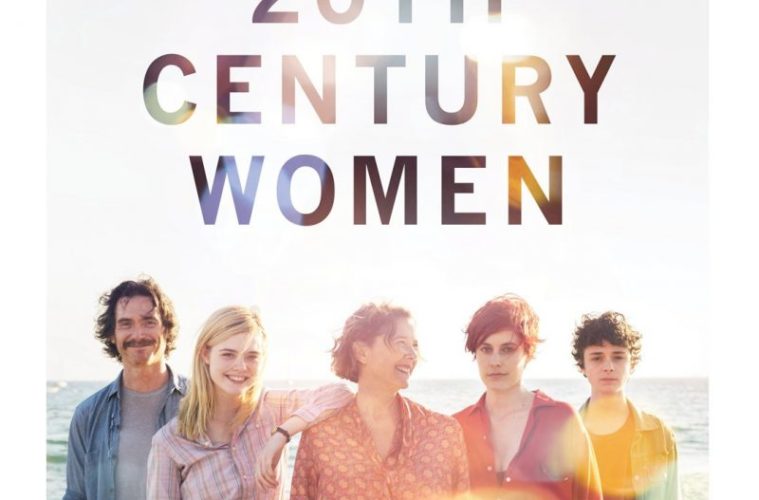

Perhaps it’s something to do with mommy and daddy issues. Beginners was a father-son story irreparably impacted by the loss of a mother; 20th Century Women‘s narrative is put into motion by the lack of a father in a mother-son relationship. “Put into motion” is about the most that can be said for the plot, primarily a series of incidents centered on Jamie Fields (Lucas Jade Zumann), a teenage boy in Santa Barbara, California circa 1979 whose mother, Dorothea (Annette Bening), tasks Abbie and Julie (Greta Gerwig and Elle Fanning, respectively), two women sharing their home, with emotional education after sensing a lack of direction on her son’s part — and after it becomes clear that her only male tenant, William (Billy Crudup), bores Jamie with his man-to-man talks about wood and other such manly things.

For however heavy I’ve made 20th Century Women sound, these sequences are largely comical, in part because the actions driving them are always well-intentioned but rarely well-considered. They are, like all else here, both boosted and complicated by its ensemble, about whom an entire review could be penned. Given that there are essentially no characters outside this quintet — from what I could perceive, every additional speaking part belongs to people whose presence affirms or belies what we know or have, through a careful accumulation of dialogue and gesture, come to believe about them — it’s not entirely an ensemble piece; nor is it a character study, notwithstanding the lack of momentous plot.

Women‘s main complication is that its energy derives from people whose proclivities are likely to earn criticism along the lines of “nobody talks that way.” Lo and behold, then, that a closed-off home located in a very particular place at a very specific cultural moment — which Mills, time and again, will make the point of emphasizing through his Beginners-esque montages, too-on-the-nose Koyaanisqatsi clip and all — fosters particular ways of thinking and being. Mills’ inclusiveness is primarily visual. I can’t recall the last film that so heavily rested the heart of its interactions on a facial expression that shifts, gradually and slightly, from one state to another. Excepting a somewhat grating faux-Eno score or the this-looks-a-bit-too-new problem that often afflicts period pieces’ production design, the atmosphere — the flow and sound of their words, the color and weight and texture of their clothing, the close-ups and wide shots capturing one or many — is very much lived-in, thanks largely to cinematographer Sean Porter, whose work boasts a vibrancy and dimension that eschews nostalgia for in-the-moment impressions of a space.

If the screenplay’s sense of scale can begin to feel limited by an overfamiliarity in environment, it’s suddenly made expansive with the realization of how much these places are extensions of these five people’s lives and personalities. 20th Century Women‘s emotional gradient grows richer (and funnier or sadder, depending on the circumstances) with an understanding of how and why those private worlds are being opened. As unbearably saccharine as that sounds, its new wave-punk soundtrack and various visual effects boost the temperament at a regular rate, while its focus on biography — the primary subject of 20th Century Women‘s objects-heavy montage — yields many amusing results. While that formal gene brings it closest to Beginners, this is less abstract for how it tells a narrative — yet, like that 2011 film, also finds truth in our penchant for narrativizing others in addition to ourselves — rather than externalizing processes for understanding the world. But it’s ultimately to the same emotional ends, which is a coded way of saying that the wallop of its final minutes are, in light of a consistent emotional wavelength, all the more shocking for their fuss-free delivery.

This, despite how readily I could spot the tools that were eliciting the response. It’s not that Mike Mills makes it look easy; it’s that he can so deftly alternate concepts and executions inside a concentrated playing field, mining what’s present for most, if not all, of what they’re worth. Expectations keep telling me these movies should be much worse, and I’m so glad to find myself wrong.

20th Century Women premiered at the New York Film Festival and will begin its theatrical release on December 28.