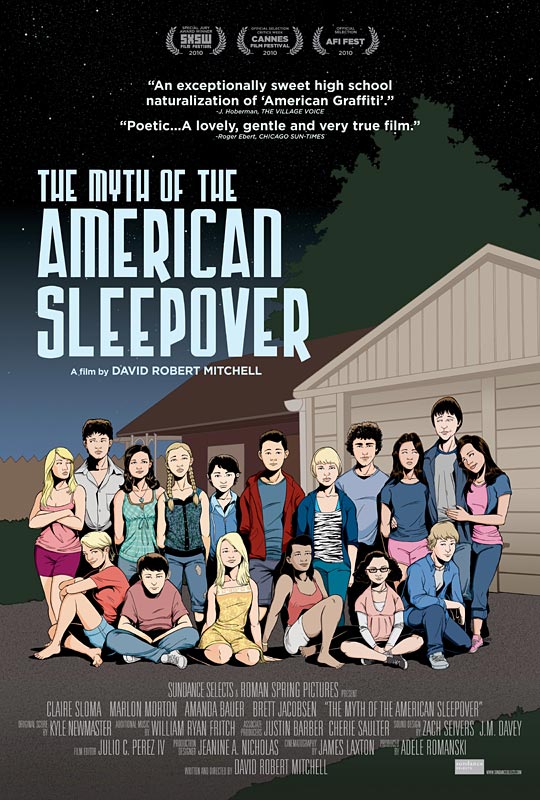

I recently had the chance to sit down with David Robert Mitchell, the writer/director of The Myth of the American Sleepover, a fun little ode to growing up. The film (which I enjoyed a shade more than Kristy did) takes place in its own removed universe: kids running amok in a world without the direct influence of parents or a sense of time outside of the sun rising and falling. David was in a good mood, still excited over the fact that people want to interview him about his movie. Long may that enthusiasm continue.

My questions are in bold, his answers follow.

How long has this idea been kicking around in your head?

I thought of the idea for the film was when I was finishing film school in 2002. I wrote it that winter, a first draft, and then passed it around, trying to find some people to help me make the movie, kind of hit some dead ends. Put the script aside and I wrote some other stuff, sort of had a day job, and a good amount of time passed. I was living in Los Angeles after film school and I just got frustrated about the fact that I wasn’t making films, and I decided to try to do that.

My good friend from film school, Adele Romanski, read the script and said, “you should try and make this movie, you should do it, and I’ll produce it.” She’d never produced a movie but she was confident about it. If you know her, she’s someone who finds ways of making things happen, which is the perfect trait for a producer. We created a plan, we went out to try and raise money, we wanted to have a real budget and we, again, we hit another dead end. We weren’t able to raise a lot of money, really, barely any. We just didn’t have those contacts and we didn’t have that track record to be able to do it. So we decided to just do it totally on our own.

We picked a start date and we just started saving money. I had my day job as an editor, I put myself on a strict budget, put as much money in the bank as I could, and when that day came I took some time off work and we went to Michigan and made the film for very little.

When you wrote it, were you writing for a smaller budget, or were there constraints that happened in a re-write or while you’re making it you sort of shrunk things down?

When I wrote it, I wasn’t worried about budget. I thought it would be a smaller movie, but I felt like it needed to have some money behind it, for sure. I didn’t re-write it [laughs] in order to do it. I think we imagined it being a lot of work to do this film for, say, a million dollars, or even as low for $500,000 would be really tough. So I didn’t re-write it and when we went into production, we spent about $30,000. I should have changed the script, I should have cut more things out of it, but I didn’t change a lot. It was fairly ambitious for the amount of money. In fact, it was probably a little…crazy. We worked really hard, we begged a lot, and we half killed ourselves and that’s kind of how we did it.

The product looks phenomenal especially for how much it cost. I don’t know if you want to mention how small.

I don’t mind saying at this point. To get to “South By,” it was just under $50,000.

Because of that, were the amount of exteriors always a part of it? I enjoyed how it was kids in their own universe. You only see one “parent” and that was a guy sleeping. Was that always the point, to put these kids in their own little vacuum, to explore them as they are there?

The idea was to not focus on the adults in this story and have it be the kids story and that kind of plays into the idea of having it be a little dream like. To me, it’s like moving through spaces in a dream. The kids moving from sort of the most iconic physical spaces of what we think of as the “teen” experience. To move from these locations that are very representative of that as if they’re all sort of very connected and very tied within this sort of imaginary geography, that was sort of the approach. Locations were super important. It was always about moving from different places and the backdrops supporting the feeling of movement within a film that is fairly leisurely paced and slow and gentle so having changes of location helps add a little bit of momentum to the story.

There were sections of just kids walking outside, trying to find where they were going. There was a lot of darkness in it. Was that a stylistic choice? The kids walking around aimlessly in the dark?

There were sections of just kids walking outside, trying to find where they were going. There was a lot of darkness in it. Was that a stylistic choice? The kids walking around aimlessly in the dark?

It’s playing in to that fun structure of what happens to people in one night. Obviously there are all sorts of symbolic parallels between this kind of journey, but starting in the day and going into dusk and them setting out on these tiny little quests at night. Then having them be just slightly different in the tiniest of ways when the sun comes up. But most of it took place at night. It was a lot of night shoots, so that dictated it also.

The cast was very good, especially considering how young they were. You mentioned [at a press screening] that casting took a about a year. Would you like to elaborate on that?

We didn’t have a casting director or anything. Adele and I handled it ourselves. People wrote about the movie in a community paper in metro Detroit and a lot of word of mouth, and we just got people to come in to audition. I was living in Los Angeles, but she and I would fly in to Michigan, stay with family, and have these open auditions at community centers and church basements. My family helped out…it was a very simple approach. Adele and I ran the auditions ourselves and that’s how we found almost everybody. They were just high school and college kids who thought it might be fun to try and be in a movie. That was it.

Were there a lot of rehearsals?

Some rehearsals, I wouldn’t say a lot. I don’t even think we rehearsed with everyone, but a good number of the actors we brought in just to see how they played in different scenes with each other. We tried to do that with everybody, even if it was only a half hour, one or two times. It wasn’t anything super long or extensive. Just enough to give them a hint of what it would be like performing when we were actually in production.

It was impressive to me how many long takes were used with these young actors being natural in the moment which is difficult to do with trained actors. Were some of them theatre kids or just…kids?

Some of them had done theatre. Most of them had never been in a movie, for sure, and didn’t have a ton of experience. I imagine some wanted or want to [act], and some didn’t, it was just a fun thing. I don’t know exactly. We were looking for people that had a screen presence, that had something natural they could bring to these parts. A lot of that was done in the casting. I would try to set a certain tone for how the scene would be played. That’s kind of my job to create an atmosphere where everyone is comfortable to relax and enjoy this and to play through the scene, whether it’s quick cuts or a long take.

I liked how there were kids in middle school–

–And high school.

And to high school, and one character who goes to college, but that’s a different sort of thing. Did you try for a wide spectrum, or was one age specifically important to you?

We tried to mix it up there. It goes from about late Junior High into mid-high school-ish and some a little bit older. Obviously one character is in college. Really it was about trying to focus on a time when you’re close enough to childhood to remember it and be connected to it, but close enough to being an adult, being caught in that middle space. It adds to wanting to do something that was inherently “good.” There is something sweet about that time.

I was shocked by the small amount of sex that’s in it. The only real point is a masturbation scene which is played out as a joke. Was that a conscious choice of de-sexing or was that more true to your experience growing up?

Truthfully, it wasn’t really our point with this film. I don’t know, those films exist but for me, it was about focusing on some kind of simpler, more innocent kind of longing. Not to say that stuff isn’t really there, because it certainly is, but this film wasn’t about that.

It seems like it’s about connection.

It is! It’s about a longing for some kind of love, even in the smallest of ways. That was the driving force behind it. It’s not a denial of those other things, it’s just the point of view about this one particular film.

What struck me was the scene with the bathtub where [the character Rob, played by Marlon Morton] visits the older sister and his focus–and the focus of the camera–is not on her, but his closeness to her hand. It’s very refreshing for the teen genre.

Because it’s so intimate, that’s the most intimate thing in that moment, the closeness of their hands. You feel that tension, you feel that with them, and that’s the point.

The 24-hour premise, with kids, the small stuff is as large to a teenager as anything else. Has it always been the case to do a self-contained structure?

Definitely, definitely. It’s a really fun structure, and it lends itself to focusing on small moments as opposed to jumping around through large spaces of time and narrowing in to find the small things.

What exactly would be the “Myth” of the sleepover? Is it tied in to the longing for the ideal and dealing with the reality that you get instead?

I think it’s layered. I think that’s a part of it. I think it’s about whether the film itself is exactly true, is exactly real, is total naturalism. I think it walks a line between a certain amount of naturalism and a bit of a dream, a bit of a memory. Dreams and memories aren’t really sharp, there’s a bit of a blur there. It’s something that’s sort of beautiful yet sometimes unclear from moment to moment. Or the specific reality sometimes alludes us in a dream, so it could be slightly different from what something really is. It’s about expecting things and having them be maybe not what you want. The film shows the reality of things but at the same time it creates its own sort of myths, because certain things in the film are not real.

How much of this film was based off your own experience? Were you trying to be as real as possible?

No, I wasn’t trying to be as real as possible. There are things that were jumping off points. Personal experiences and the things I saw in other people were sort of the beginning of it. But a lot of it is imagined, things that I maybe wanted to have happen at the time, or that I thought about, or that even in retrospect I thought characters might want to have happen. There’s a part of my personality in a lot of the characters in the movie. It’s definitely a very personal film, even if it’s not a completely autobiographical film.

My favorite line in the entire film is when one character gets egged, and his friend said, “sorry man, we had to.” That is the most wonderful teenage thing of the weird conflict of how he didn’t have to, but he had to. How was it tapping in to that weird logic again?

That was just trying to remember the things that happened or things like that happening. The funny cruelty that passes as friendship within circles. I don’t know, I don’t know why we were like that. But I definitely witnessed those kinds of things. I don’t know if I was the one getting egged or the one throwing them…. That particular moment is fabricated, at least as far as I can remember it is.

But at the same time, I feel like I’ve had something to the effect of getting egged before. I think most people have. At some point, growing up, we’ve all been egged. You’ve also done it it or been one of the kids standing in line with the people who have just done this and feeling a little bad about it, but not being able to take it back.

The other line piggy-backed off of that is [his friend saying], “I had nothing to do with it.”

Yeah, as if that makes it okay.

A lot of these characters work on odd moral planes. It’s that weird cruelty, seeing someone get cheated on and how they respond to that. Was that something that you were very conscious of in the writing process, that there isn’t a strict moral code to these characters?

Well I think they’re inherently good. But I think everyone makes mistakes and it’s pretty normal to. Most of them, even the characters that are doing something that you might think of as being “bad” or “hurtful,” I feel like no one is ever villainized. The idea of having a protagonist and their arch-nemesis in a film is sort of odd to me and I don’t think it’s very necessary. Of course, there are films where there is, but in this film, that’s not the point.

How much did the kids inform the characters as you were making the movie?

We didn’t really change dialogue and most of the scenes were played out as written. There was little to no improvisation except for the smallest of things. They did inform the scenes very much just by being who they were. Part of the magic of casting this movie is I have them written a certain way and just the simple act of casting someone in a particular role brings so much to it. Just a certain face dictates how the audience will see that person and how they’ll care about them. In that sense, what they brought to it, was huge. The film, without their individuality, what was unique about each of them. Without that we don’t have a movie. We don’t have anything that anyone wants to watch, so they’re essential to this thing being anything.

The Myth of the American Sleepover screens at the Angelika Film Center in New York starting today with a national roll-out to follow. It will be available On Demand via Sundance Selects July 27th.