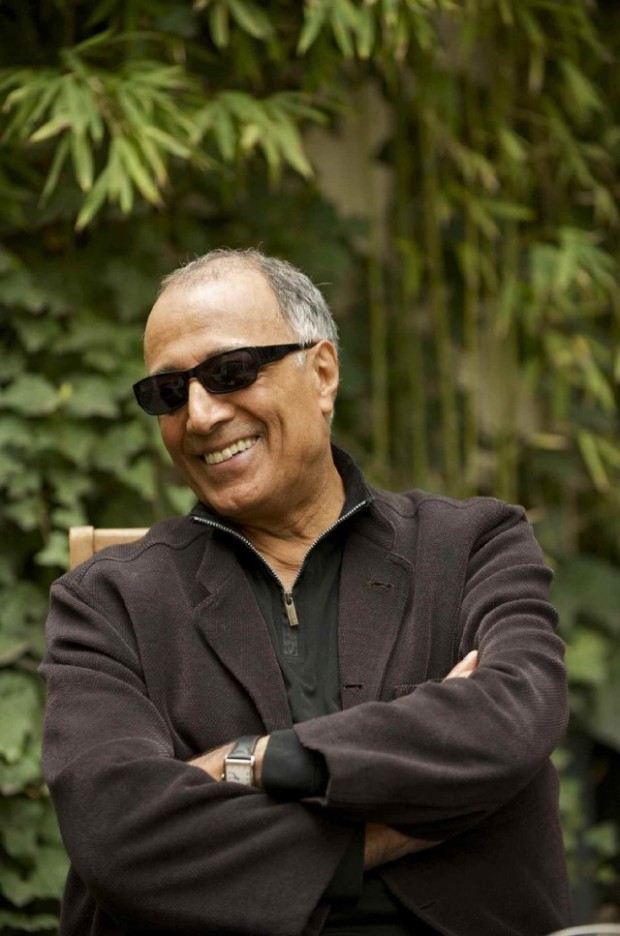

Abbas Kiarostami is considered by many the champion of Iranian cinema by making films that embodied an enigmatic point of view on culture, art, society and the relationships people have with one another. However, for the past several years, the filmmaker has been working outside of his home country due to a volatile political climate. Certified Copy was his first film made outside of Iran, shot in the gorgeous landscapes of Tuscany, Italy and featuring two magnificent performances from its leads Juliette Binoche and opera singer William Shimell.

For his oddly similar follow up, Like Someone in Love, he decided to head far east to the land of the rising sun for a different kind of inspiration. Having seen the film when it premiered in Cannes, it has lingered in my mind ever since. I was fortunate enough to sit down one on one with the legendary auteur during the New York Film Festival to discuss the many complex facets to his style of storytelling and why his films’ mysterious qualities are what draws his audiences in.

The Film Stage: Where did the inspiration for this particular film come from?

The Film Stage: Where did the inspiration for this particular film come from?

Abbas Kiarostami: The idea was triggered in Japan itself. I was in Tokyo long ago, like 17 or 18 years ago. We were driving through the business area late at night and I saw this young girl dressed as a bride on the sidewalk and this image was so powerful that it remained with me when I went back to Iran and then through my travels when I went back to Japan. I would go back to Japan almost every other year for the promotion of my different films and different events. And I realized that I was still looking for the same girl, the same image that I had found so striking at the time and I never saw this image again because the girl did not have this uniform anymore but the reality was still there under different costume.

Did you have to adapt your writing style to Japanese social conventions to write the script?

No, not at the time I was writing. When I was writing it was in my own language and then obviously in my own culture, so I tailored it as sort of a universal story that could happen anywhere. But then where we went there I had to have my characters and the society, which this story happened prove it and see if it did fit them and there were small details that had to be corrected. For instance, if she enters a room she has to take off her shoes and they don’t shake hands and he cannot touch her face when he’s trying to heal her wound. These were small details that were more loyal to Japanese appearances. But deep inside it didn’t change anything. I didn’t want to make it too Japanese over aesthetically Japanese because I didn’t want to make a touristy film and give some clichés about Japanese culture or habits. I wanted to have a right appearance but then to focus on the universal aspect of the people and the characters in the story.

What have the challenges been directing in another language besides your native tongue? And how does that affect the actors?

It wasn’t such a big issue for me, the translation or the language obstacle, because I did it as I already do with my Iranian actors, I give them very little information. I believe that one of the most important phases is the casting. Once you’ve chosen the right people you should not interfere too much in what they have to offer you. So you just give them the minimum information and then you let them be, you leave them enough space to express themselves. That’s what I do with the Iranians; I give them the little information that is needed. I would give it through translation and then let them react as they did naturally and so I just felt that they were ready and there was not much about language, what happened between us. I would just say that I don’t really believe in a constant actor-directing. Actors don’t need, in my way of working, to be directed. They need to be carefully chosen but once they are and once they’re given the outline, they are the ones who work and we are just there to overview it. Even at the time, I remember when I was young, it was a joke, I said “I’ll go to Japan someday and make a film and see how they react.” But then the Japanese actors happened to be just as Iranian actors.

One of the things I love about your films is the mystery behind everything and there’s an enigmatic quality to trying to uncover everything that’s not said. I’m just wondering, in this film particularly, there’s themes of perception and then preconceived notions. Was this intentional and was this one of the main things you were trying to touch on?

Yes, there is a difference between the relationship that this girl has with the pimp, though you can tell that they’ve known each other for a long time and they’re referring to a common knowledge, a common experience and then when she meets with this older man. It’s not that there is mystery, it’s just that there is ungiven information because at that stage we’re not supposed to know everything about him yet. All we know about him is through small hints like pictures in his apartment or something that you can tell from the way he lives, that he lives on his own, but apart from that it’s a first meeting so we are witnessing whatever goes on between them for the first time. There’s nothing that’s pre-given or pre-stated.

[Note: Spoilers for Like Someone in Love occur in the next exchange, so skip ahead if you haven’t seen the film.]

One of the most interesting elements of this film is the ending and the impact it has. For me, I saw the film in Cannes and I remember leaving the theater and everyone’s buzzing about the abrupt nature of the ending and I’m wondering, did you intentionally want to break people’s expectations for when the story would end and is it also a kind of ignition to talk about the film more after it’s done?

I think the surprise that you felt, or the audience around you felt, I shared the same feeling at the moment I wrote the ending. I was writing my story and it got to that point when the stone hit the glass, I just saw myself writing the end in English and I chose even the title of the film, the end was also the title. So I finished writing it and I sent it to my translator and my producer expecting them to say it wasn’t a proper end for the film and thinking that I had time to think it over and find a different ending. But then the process of the preproduction took two years, because of the tsunami and things postponed it, and during these two years I never found a better ending. I realized that there was something very deep going on, that there wasn’t only a glass that was broken but also the respect and their reputation of this old man who had lived in this neighborhood for 50 years — that was all of a sudden completely questioned. It was a kind of climax and there was nothing more I could add to it. So I accepted it as an appropriate ending and even at that stage if anyone else has a better ending, I’m open to receive their suggestions.

Your use of cars and reflections of landscapes within the cars is something that is throughout your body of work and I’ve always been curious, why is the car such an intimate and central point for your films, to expose not just the inner character but the outer world that’s passing them by?

I’ve made a film called Ten on Ten in which I give some general explanation about my work and there’s a whole chapter about the car. There are many different reasons that make a car a very interesting location and a place for conversation and dialogues to take place. But I keep being asked this question, on and on, people keep asking me, and so rather than answer — because I find it a bit annoying to have to answer again — I just ask the question of ‘why do people ask me?’ Because I think it’s obvious, I think the reason you said that there is this intimate place and the other landscape, and because I’m looking at you and behind you the background is totally flat and uninteresting, whereas it could be a landscape. There are plenty of different reasons.

So once that we acknowledge that this is such an interesting and attractive location, why do people keep asking me? They never ask other directors or myself, why do you choose a boring office as a place for people to have a conversation or a bedroom or living but the car I have to justify myself I find it a bit unpleasant. For example, in this film, there is such a long sequence inside the car, from the morning when it opens until the moment she gets off. It’s a very long sequence but I was asking my translator if she noticed how long it was but no one noticed and the reason we don’t is because it makes sense, it’s the point of view of the character and so the mise-en-scène is very complex. It’s not easy to know how to organize the mise-en-scène in a car so I cannot say that I chose to choose it out of comfort or in ease but I still feel that I find it a very interesting and attractive place for conversations.

Apologies for adding to the problem…

I’ve gotten used to it. Yesterday, I even apologized to the audience because they asked me the same question and I thought maybe I’m pushing something sensitive for you, maybe I should quit. I could stop with the cars. So I could promise that I would quit, but then I realized that my next two scripts that I’m working on have car scenes in them, so how could I quit?

Talking about your documentary Ten on Ten, it was a very fascinating film about digital cameras in a way that had never really been done before and I’m curious to know if you ever had thoughts about creating a film that deals with the same kind of shift in technology concerning the Internet. Is that a thought that ever interests you?

Well, I might not have the opportunity because I don’t use them. I’m very old-fashioned and I don’t use them, but I’m quite fascinated to see how people are dealing with new media and new ways of coming together and communicating but it’s not my world. I’m sure that people who are into it get inspired by it and there is a real subject, but for me it’s secondhand. I don’t really pay attention to it myself because I don’t use it.

Is there a country that you really want to make a film in that you have not?

Well, no, there’s not one country that I can think of but I do acknowledge the location, a specific city or place or region can be fascinating enough to be the motivation of a film in itself. To go and see the people of that place and the place itself, especially if you believe like I do that people are the same wherever you are, so it’s always attractive to go to new places that you have no clue of. Somebody suggested to send me to a tribe in Australia or Africa, even if they are cannibals. I mean, we do eat meat too and this is something common between them and us and I would love to go to unpredictable places.

Like Someone in Love screened at NYFF and will open in the spring via IFC Films.