Jacques Rivette, in speaking of Paul Verhoeven, said the Dutch filmmaker’s philosophy was “about surviving in a world populated by assholes.” Every one of his films takes the world’s rotten core as something of an absolute given, and, in turn, the only minor victory that’s even possible is merely getting through it all. In fact, “minor victory” would be the key term: although his science-fiction works essentially abide by traditional “action-film” narratives, the ends their protagonists reach are never truly instances of good conquering evil; many even straddle the very line between these two moral classifications.

With a remake of one of his classics hitting theaters today, we take a look back at his quartet of science-fiction films. Read on below:

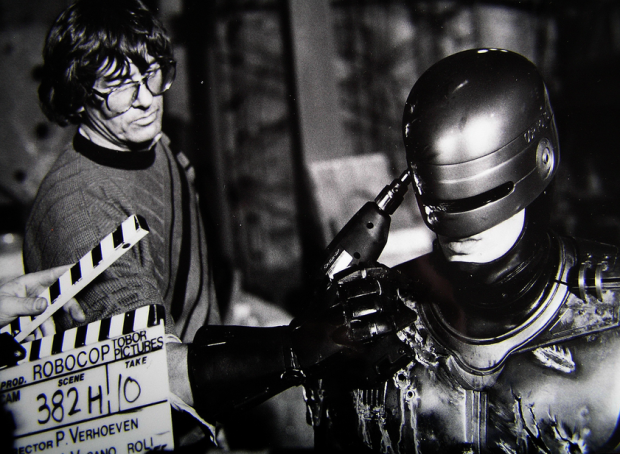

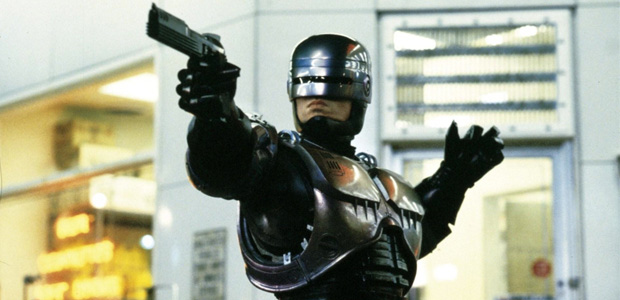

RoboCop (1987)

Instead of an action-packed sequence centered on its title character, RoboCop begins with a television broadcast, establishing in one fell swoop what is, seemingly, the entire state of both future Detroit and that not-so-distant-future America’s culture and politics: the reduction of news to minute-sized bites, omnipresent Reaganomics, and, most hilariously, the promise of many ridiculous consumer goods, which would naturally take up equal screentime as this so-called televised journalism. But this future Detroit is most frightening when shown to be in the corporate possession of seemingly every public service — including the police force, which is in heavy disarray due to rampant crime.

Interestingly, however, the film makes a point near its beginning to compare the fatalism of each corporate and police sector: the risk of a younger executive popping in with a new idea for the former, the constant officer deaths within the latter, and the eventual overlap between them resulting in the creation of the titular half-man / half-machine.

The fallen Officer Murphy is basically rebuilt to be a cliché, as so naturally fits within a world which consists entirely of catchphrases. Yet what Verhoeven provides, with Murphy, that he doesn’t communicate through other characters is point-of-view; once Murphy is transformed, his vision has become malformed into what’s essentially a surveillance camera. Eventually, though, the only sense of sight this man has are his memories — the one instance in which his wife and child are actually seen, and could thus actually be said to exist. Every one of Murphy’s point-of-view shots renders him as either opposed or alone, particulary when seen moving through the private space of his vacated old home that, now, is just another consumer good for sale, or through the public spheres where’s he regarded in a godly fashion, if not as an actual being.

Perhaps this is why RoboCop is, ultimately, Verhoeven’s most emotionally engaging film, being that it’s a narrative of self-realization. The identification with the machine is central to Verhoeven’s personality: always siding with the freaks, or, more aptly put, victims. Specifics of sympathy are, still, a tricky thing to pin down in his films, as anyone who isn’t the recipient of it is likely subject to the most brutal and mocking of violence, including a shot to the crotch of a potential rapist that channels the castration-panic so key to many of his films (as most explicitly expressed in his Dutch thriller The Fourth Man).

Of course, considering Verhoeven’s familiarity with erotic films, that the human body is central should come as no surprise — but what RoboCop exemplifies is his eagerness to not just peer at it, but also turn it into a cartoon. There’s the blown-apart body of an executive in the ED-209 massacre, or even the two-part joke of a criminal goon being mutated by acid and, then, swiftly getting decimated by a moving car.

This, while emblematic of why Verhoeven could never really be labelled a “humanist,” at the very least sets the stage for this film’s concluding “Murphy, Sir.” Just the utterance of one thing genuine is, by the end, somewhat of a triumph.

Total Recall (1990)

Continuing in RoboCop’s path, Total Recall follows a character’s self-realization in a cesspool of a future world selling product after product — yet instead of having him be its victim, he is, instead, navigating the very transparent pleasures it’s built upon, in particular the new identity that a product supposedly promises.

While treading a line between fantasy and reality, Total Recall doesn’t necessarily emphasize subjectivity in the sense of point-of-view camera work (e.g. RoboCop), but, rather, by creating a world where it’s impossible to not be looking at something. (Television screens are scattered throughout personal and public spaces, from the home to systems of transit.) It’s only natural that the protagonist, Quaid, would be lured by both the personal and the commercial, for he can only attain his dream of Mars through a phony contraption simulating the actual experience — which naturally raises the question of if “the following” is real, or merely the kind of male escapist fantasy peddled out every week in cinema and on television.

The caster of this gaze is played by Arnold Schwarzenegger, who, while obviously unable to serve as a relatable everyman à la Peter Weller, Verhoeven carefully uses to subvert star image itself. While Schwarzenegger was cast early in his career for an imposing stoicism, Total Recall instead makes him as expressive as possible, even contorting his body to plastic heights via various make-up effects, such as the hilariously grotesque way his face and eyes bulge from exposure to Mars’ surface at both the film’s beginning and end.

Unlike any other Schwarzenegger picture, however, the repercussions of his actions are initially in complete view; when Quaid looks at the blood on his hands after the gunning down of multiple goons, there is then the cut to a bird’s eye view of all the dead bodies left in his wake. Yet he seems accepting of it, later relishing one-liners and violence as he gets deeper in, thus coming closer to the typical Arnold Schwarzenegger protagonist. Quaid’s conscious choice is to avoid pacifism and favor the near-nihilistic retaliation of the action-hero.

Yet being that Quaid is still the dominant white male, Verhoeven’s sympathy is more towards Mars’ deformed mutant inhabitants who Quaid ends up helping. A Marxist tract is even formed through their narrative of being workers screwed by a greedy business head (Ronny Cox more or less reprising his role from RoboCop), and subsequently working to overthrow him through revolution — or, as more commonly referred to on the all-knowing television screen, terrorism.

But while this revolution seems to have ended in success, was it even real? Quaid even questions this, but he’d rather see the victory in this ambiguity — and, if nothing else, that’s his choice to make.

Starship Troopers (1997)

While his past decade of films saw Verhoeven acting as a European outsider satirizing America, Starship Troopers‘ position as a direct allegory for fascism proved more directly personal to the survivor of World War II. It serves as the middle chapter of his unofficial trilogy on this war, though, being the only American entry, it perhaps had to be told through a very overt genre construct of the science-fiction blockbuster, disguising the tenets of Nazism under the guise of computerized spectacle and typical white heroes.

Yet by being told through the perspective of the militaristic superpower instead of the repressed, Starship Troopers is the also most aggressively satirical of his films, to the degree that even character identification is subverted. The film’s leading man, Casper Van Dien, is perfectly cast as Rico, considering both his disturbingly Aryan features and seeming lack of anything which resembles personality — further making him a perfect cipher, as far as both action-film heroes and easily manipulated youth go. Even the film’s exceptionally bright lighting — an aesthetic choice that would even more overtly recall an episode of Beverly Hills 90210 in its high-school-set first act — is willfully deceptive, masking an essentially evil future in which both contemporary and classic clichés form a fascist society: a merging of the industrial entertainment of the ’90s and the propagandist war films of the ’30s and ’40s.

And, as with RoboCop, clichés are the film’s strategy, be it bargain-bin philosophy from teachers, fascistic jargon from drill sergeants, or, perhaps most importantly, jingoistic narratives assembled from media, even in the immediate wake of genocide. Fascism’s ultimate victory is the acceptance of these building blocks into everyday life and, concurrently, a failure to challenge them. Even the concept of citizenship — reinforced by both figures of authority and television as the ultimate status — is never actually articulated as to what it really represents or provides; it, rather, is another object shamelessly peddled out for sale from the media. Starship Troopers’ future is even more oversaturated with bullshit than what’s seen in either RoboCop or Total Recall.

This concept of citizenship extends to the similarly vague reasoning for attacking the bugs, who almost serve as the penultimate Verhoeven victim; rendered as the other through design, it’s immediately easy to misunderstand the creatures as blockbuster target fodder. But as the invaded and not the invaders, they’re far more sympathetic than all the bland humans, like our hero.

While Rico’s a lunkhead to the very end, his transformation comes in attaining an identity through fascism, as opposed to Murphy or Quaid’s eventual rebellion against becoming cogs in some larger machine. He loses freedom of choice, which he’s been (even ironically) reminded of as his only real freedom by an authority figure.

Important, too, that war’s realities are still present: all the veterans are disfigured in some way, but have been passing it off like a necessary rite of passage. In comparison, the soldiers’ bodies being ripped apart by computer-generated bugs highlight a key absurdity of the situation — real versus plastic carnage. Of course, to Verhoeven, such absurdity is likely the only thing which could actually represent something so horrid yet inherent to mankind.

Hollow Man (2000)

Hollow Man’s opening scene — a sacrificial rodent being disemboweled by one of the invisible test subjects — appropriately sets a stage for the film’s savage (even for Verhoeven) world: one belonging primarily to either male chauvinists or slasher-film ciphers. The question comes though to whom Verhoeven ultimately sympathizes with. Who’s the survivor in this “world populated by assholes”?

Unlike Murphy or Rico, the film’s lead, Sebastian, is provided with too much choice because of his newfound state, as if invisibility now makes him a God on Earth. While Quaid certainly lived out his own fantasy, Sebastian is placed in a far-more-contained world; it seems that Sebastian’s actions come almost more from boredom than actual malice, his workplace rivalries and antipathies blown up to murderous heights simply because they can be.

The biggest of these is his passive-aggressive relationship with fellow scientist Matthew, chiefly in regards to his relationship with Sebastian’s ex-lover and current co-worker, Linda, their first scene together being a work argument very thinly veiling machismo posturing. The visual gag in this scene articulates it all so very well: Kevin Bacon in his leather jacket and Josh Brolin in his workplace nurse uniform, the former clearly positioning himself as the “cool guy.” This instantly recalls RoboCop’s own shifting corporate executive hierarchy, showing that it exists in any work environment filled with males — even when supposedly in the name of science. Within this space, everyone discusses what they’d do with invisibility, hinting at its darkest possibilities as if it were a joke — but Sebastian, already an asshole and dork at the film’s beginning, proves how it’d really be utilized.

Verhoeven using a subjective camera for many of Sebastian’s acts could be argued as less “his touch” and, rather, just embracing conventions, considering to what extent extended first-person visions became a major crutch of the slasher genre. (Just think of the opening horror spoof from Brian De Palma’s Blow Out, which seemingly takes jabs at Halloween, Friday the 13th, and Black Christmas.) Yet while Hollow Man seems most absent of the media presence that characterize the three preceding films, Sebastian’s sexual voyeurism — such as peering into his attractive neighbor’s window — is instantly comparable to a screen, recalling Hitchcock’s same assertion with Rear Window. Sebastian attains the goods that he thinks are promised to him — the subjective camera work, as usual, achieving the sense of killer perversity — only to break out of it (however briefly) because of his sympathy for the victim. The sequence ends with a camera move that pulls away from her bruised body, for Verhoeven isn’t ever one to deny the repercussions of his monsters’ actions on the innocent.

Camera movement isn’t the only reason Hollow Man seems like no more than a technical exercise at times; just count the number of instances seemingly created only to highlight the effects with water or smoke outlining Sebastian’s form. That being said, in the body becoming completely digitally rendered, the film attains something Verhoeven was continually seeking: the male form reaching complete plasticity. Maybe, in this case, that’s the only way to make his most despicable character even plausible.

What’s your favorite sci-fi film from Verhoeven?