Why don’t we address the elephant in the room? Fourth of July is of course the surprise new film from Louis C.K., which as pitted against the decadence of previous directorial effort I Love You, Daddy—recognizable stars, black-and-white cinematography, taboo subject matter—made at the height of his influence, becomes a very curious object. But still not fun to watch. Comprising no-name actors, virtually zero production value, and an extremely small-scale story that would bore most despite any relatable themes, this can be surmised as either the work of a man on the ropes or one who really doesn’t care much anymore.

Our sympathetic protagonist being Jeff (Joe List), a New York jazz pianist who’s also a recovering alcoholic. In presumably his late 30s or early 40s, he’s hitting the point where he should probably decide what form of adulthood will define the rest of his life. With his wife wanting a child, Jeff realizes he needs to finally make peace with (or tell off) boorish elders before feeling ready to parent. As a story of confronting one’s unresolved trauma and insecurity, there’s certainly emotional stakes for the creators of this film—as one could at least gather from glancing at star and co-writer List’s Wikipedia page. He, unfortunately, isn’t the most compelling lead. Maybe someone could compare this nebbish-looking, barely funny (or even nerdishly charismatic) screen presence with how Kubrick used non-entity Ryan O’Neal as deliberate window dressing in Barry Lyndon, but not feeling drawn to his journey in such a modest project is a major issue. You almost can’t blame surrounding parties for bulldozing over him.

And emotionally bulldozing will happen: who he must confront beyond just his parents is the vulgar, extended New England family who down Bud Light, make casually racist remarks, and create a generally toxic knockabout atmosphere. If “arty kid who doesn’t fit in with vulgarian kin” isn’t the most compelling setup, Fourth of July at least bears some emotional grounding in its thesis that saying “fuck you” to those you hate rarely offers catharsis.

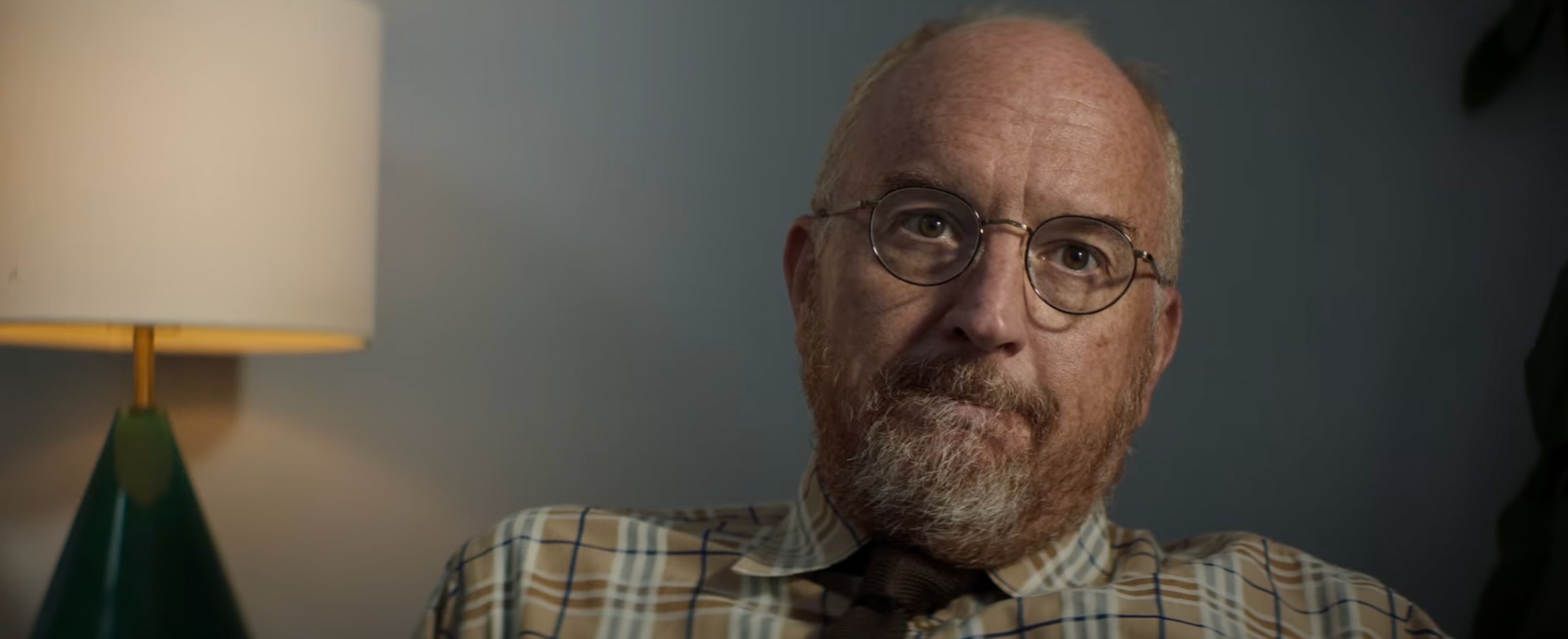

If its humanist aims are mildly respectable, one still expects something a little more incendiary as a “post-cancellation” work (the same issue with Woody Allen’s rather lazy and low-stakes Rifkin’s Festival) from Louis C.K., and really the only conceivable thing to get upset about is the film’s slightly condescending use of its one black character, a case of “good guy” syndrome gone bad. Yet it seems a fool’s errand to ascribe that much authorial presence to the controversial comic when it’s perhaps more List’s passion project that was directed as a favor. (C.K. in a small role as his therapist probably represents their real-life dynamic.) His duty as a helper seems to be splitting the difference between modest and lazy filmmaking, with hardly the most dynamic 2.35:1 framing and occasional wide-angle lens distributed when audiences turn bored by lack of beauty.

Fourth of July most recalls an earnest, drab indie drama that would be filler at the Tribeca Film Festival. No matter where you stand on C.K.’s “reemergence” into the public eye, it’s a little disappointing that all he could muster was a platitude. Certainly a plea for people to forgive could’ve been made with a little more passion.

Fourth of July opens in theaters July 1.