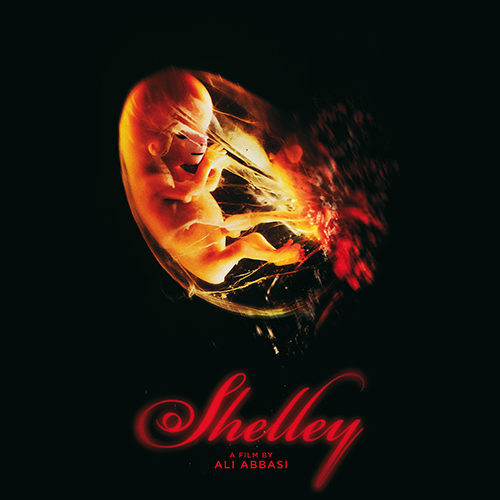

Everything starts so innocently that you’d be hard-pressed to realize Ali Abbasi‘s Shelley is a horror film besides the score’s dread-inducing soundscape rising to a deafening level of static. Sure the setting’s weird with Louise (Ellen Dorrit Petersen) and Kasper (Peter Christoffersen) living in the Danish woods without electricity or running water far-removed from civilization, but the world’s fill of eccentrics. They’re actually quite nice, bringing in a new maid (Cosmina Stratan‘s Romanian single mother Elena) with open arms and warm smiles. It takes some getting used to, but the newcomer is quite content after a while. She adjusts to the quiet, regularly calls home to speak with her mother and son, and resigns herself to the prospect of returning after two to three years accumulating salary abroad.

In a moment of bonding Elena and Louise speak about motherhood to reveal the tragedy of the Dane’s past. Not only did Louise lose a daughter well into pregnancy, the result left her without a womb to try again. Pairing this tale with Elena’s drive to accrue the cash necessary to support her family, a proposition is struck. Rather than wait years the young woman can go home in nine months. If she carries Louise’s frozen egg to term she won’t even have to work anymore. The couple will care for her and pay for the trouble with a Romanian apartment of her choosing. Elena doesn’t jump—she’s been pregnant before after all—but she likes her employers. They’ve become friends and the mutual benefits can’t be denied.

Here’s what is so brilliant and extra creepy about what Abbasi and co-writer Maren Louise Käehne created: nothing is amiss and no one has ulterior motives. Their film doesn’t just start innocently. It is innocent. Louise and Elena become like sisters, joking, laughing, and attending doctor visits as any two women engaged in a surrogate arrangement would. When the latter falls ill with headaches and skin rashes, the former is by her side in an instant to do all she can to assist with support. Louise even enlists her holistic advisor Leo (Björn Andrésen) to stop by and alleviate the girl’s pain with spiritual healing to exorcize any darkness. Everything seems calm and safe. But while the fetus is declared healthy, no one can ignore Elena’s waning vitality.

We start to question whether or not an evil is lurking. Maybe we were wrong. Is Louise playing a role as the doting caretaker? Is Leo’s presence introducing some sort of satanic incantation, preparing Elena’s body to bring forth the antichrist? Perhaps this stranger has been playing us from the beginning, Elena’s kind and simple maid knowing the history of the family bringing her in and exploiting them for personal gain. Had this movie been made in the Hollywood system each of these possibilities would have at least been taken into consideration with one or more chosen. But Abbasi relents. He lets us question how we’ve gotten where we are yet never disregards his goal of providing an autonomous malevolent being we can never wrap our heads around.

The first third is a courtship, the second a devolution of physical and psychological stamina. I’ll leave where the final third goes to the film’s ability to sink its claws in and drag you down. Abbasi hints at the surrealistic horror forthcoming by planting nightmarish visions in Elena’s head—seeds of the title before the name’s ever spoken and the devilish hell slowly consuming them whole. This pregnancy has the Romanian unable to touch water, waking with blood-covered lips, and constantly fatigued with a craving for pure sugar. The latter two (no running water makes the bath full of that which Mother Earth supplies their well) are obvious demonic earmarks, but again there’s no reason a demon would be involved. Our confusion only makes the suspense more potent.

We watch with baited breath for the introduction of a cause. We wait for Louise or Leo to tip their hand; the doctor to make a mistake and reveal her dark magic; or the filmmakers to go inside Elena’s head so we can discover nothing has quite been what it seemed. We need these answers because they’re what we’ve been conditioned to find within the genre. And the longer it takes to receive that which we need, the more strained the situation becomes. Suddenly maternal instincts kick in and the terror infiltrates those who appeared immune to it. Crazy becomes an adjective to describe everyone, each finding him/herself at the cusp of self-mutilation or homicidal thought. So little happens and yet so much changes from start to finish.

Shelley moves at a methodical pace so don’t be alarmed when frustrations set in, because it’s all drama without scares. Atmosphere and mood are the film’s strong suit, both growing thickly heavy as time elapses and strange occurrences commence. Our being left in the dark is effectively intentional, our minds racing to figure out truths that might not exist. We see everything from the outside as voyeurs next to Louise, not hearing the clicking Kasper does or feeling Elena’s burning flesh. All we know is that a baby’s coming, the one thing she’s hoped to have in her arms for years. The rest is noise—delusions brought on by insecurities and fear. How far will Louise go to ignore that tumult so she may finally embrace her child?

Shelley screened at the Fantasia International Film Festival and opens on July 29.