Dailies is a round-up of essential film writing, news bits, and other highlights from our colleagues across the Internet — and, occasionally, our own writers. If you’d like to submit a piece for consideration, get in touch with us in the comments below or on Twitter at @TheFilmStage.

Alexandre Desplat will head the 2014 Venice Film Festival jury.

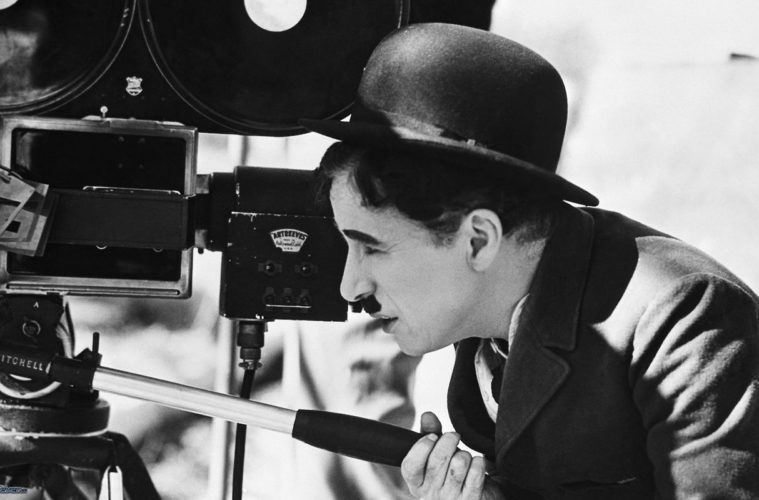

At AV Club, Ignatiy Vishnevetsky explores why Charlie Chaplin still matters a century later:

Charlie Chaplin was famous in a way that no one had been before; arguably, no one has been as famous since. At the peak of his popularity, his mustachioed screen persona, the Tramp, was said to be the most recognized image in the world. His name came first in discussions of the new medium as popular entertainment, and in defenses of it as a distinct art form—a cultural position occupied afterward only by the Beatles, whose own era-defining popularity never equaled Chaplin’s. He’s the closest thing the 20th century produced to a universal cultural touchstone.

Christopher Nolan‘s Interstellar will be projected in 70mm at around 50 IMAX theaters, Collider reports.

Also at AV Club, Mike D’Angelo revisits The Big Heat:

Fritz Lang’s The Big Heat opens with the suicide of a police officer—out of uniform, in his own study, for reasons that don’t become clear until later. From the opening credits, Lang dissolves to the image of a snub-nosed revolver on a desk, portending doom. Sure enough, a hand soon reaches for it, and as the camera pulls back slightly—carefully keeping whoever’s now holding the gun out of frame—a shot rings out, followed by a puff of smoke, and the policeman’s lifeless body falls forward onto the desk. As his wife runs down the stairs to see what happened, Lang cuts to a shot that slowly tracks toward the corpse from the opposite angle. However, apart from the gun in his hand and the previously heard shot, there’s nothing to indicate that a bullet just entered his head, or even his chest. No blood is visible anywhere, and the cop looks roughly as he would had he just gotten tired while working and taken a nap at his desk.

At Flavorwire, Jason Bailey looks at how Batman, which just turned 25, changed summer blockbuster season forever:

The poster was simple, but it was genius. The logo was giant, spilling off the sides of the page, a clean, sparkling, orange-and-black design. Across the bottom, in a simple, white typeface, was a date: “JUNE 23.” That was it. It didn’t tell you what movie it was for; it didn’t spotlight the prominent, marquee names of its stars or its director. It didn’t have to. No one in America who was paying more than passing attention to popular culture had to be told that there was a Batman movie coming in the summer of 1989; it was the most anticipated movie of the season, and that poster knew it. It knew you were waiting for that movie, and it contained one simple bit of information: you could see it on JUNE 23. That was 25 years ago, and with the benefit of hindsight, it’s easy to see how Tim Burton’s Batman ended up being one of the most influential films of the modern era — not for what was on screen, which was hardly even relevant. What Batman changed was how the movie-going audience was prepared for summer blockbusters, and how Hollywood grew to depend on them.