Maren Ade has kept us waiting. It’s been seven years since her superb second feature Everyone Else premiered at the Berlinale, taking home the Jury Prize, and she’s spent the interim collaborating on the production of other people’s films (e.g. Miguel Gomes’) rather than releasing one of her own. Now that her new directorial effort is finally here, it validates all the eager anticipation, as Toni Erdmann is one of the most stirring cinematic experiences to come around in a long time.

For Toni Erdmann’s first third or so, Ade seems to be revisiting similar territory to that of her excellent, albeit little-seen, debut feature, The Forest for the Trees. The two films’ protagonists are kindred spirits: profoundly kind and well-meaning persons whose obstinate insistence on thrusting their support onto others, oblivious to the fact that it isn’t welcome, borders on the pathetic. The new incarnation of this persona is Winfried (Peter Simonischek), a pensioner living alone with his dog and whose daughter, Ines (Sandra Hüller), is a successful and globetrotting corporate consultant currently on short-term assignment in Bucharest.

When they first meet early in the film, on the occasion of a quick stopover home by Ines, it’s instantly clear that they do not have the strongest bond. Winfried’s constant attempts at making jokes or pulling pranks – he shows up in full-face zombie make-up and always carries a set of grotesque fake teeth in his breast pocket, which he wears any time the atmosphere grows stale – are met with barely suppressed disdain and each one of their exchanges quickly disintegrates into silent awkwardness.

This dynamic is resumed when, motivated by the death of his dog, Winfried pays Ines an unannounced visit in Romania. As she takes him along to a meeting at the American Embassy and to cocktail parties and expensive bars, the unkempt, unsophisticated Winfried is a repeated cause for embarrassment. Popping in his fake teeth and cracking jokes at inopportune moments, he bewilders Ines’ friends and business partners, alienating her even further. Things don’t improve when they are alone, as Winfried’s genuine but misguided attempts at reconnecting with Ines — e.g. by offering her an ingeniously designed cheese grater that she all but scoffs at — fall horribly flat. The social situations are acutely cringeworthy while their private moments are heartbreaking, eventually culminating in an unceremonious farewell.

Though these scenes can be very difficult to watch – some are downright excruciating – they offer a sharply incisive, if extreme, representation of the conflict between one’s natural obligations to their parents and the difficulty of actually fulfilling them as an independent adult. Ade’s script is a paragon of complex, nuanced characterizations. As cold as Ines might act towards her father, her position is fully relatable. Winfried may be a lovable fool, but few would put up with his antics, best intentions in the world or not. And as gauche as Winfried might be, he comes off a lot better than all the suited-up assholes with their business cards and trophy wives who populate Ines’ milieu and whose estimation she so desperately covets, which in turn reflects equally bad on her.

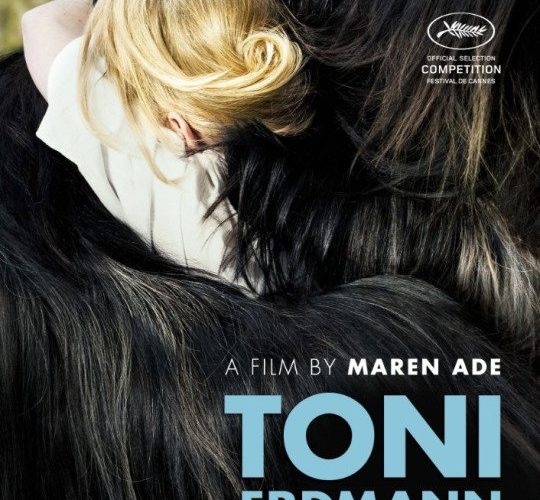

Once Winfried returns as Toni Erdmann, a ludicrously bewigged, rotten-toothed oaf who wears a scruffy suit and claims to be a life coach, Ade’s film makes an unexpected turn, becoming something far greater than an updated, polished version of her debut. It also becomes very, very funny. (Yes, a German film that is genuinely uproarious – miracles do happen.) Toni first barges in on a dinner Ines is having with two girlfriends, spouting nonsense about business and life-coaching and generating great amusement amongst Ines’ company. All the while, she pretends not to recognize him, preferring to go along with the charade rather than having to endure any more mortification. These unexpected appearances keep occurring and Toni ends up meeting Ines’ boss as well as her lover, tagging along on a dismal, coke-fueled party at an awful nightclub, and even sitting in on business meetings.

More than simply exposing the hollowness of Ines’ career and social circle, Toni’s repeated intrusions into Ines’ life impel her into a gradual confrontation with the fact that she is fundamentally, critically miserable. Were this a feel-good Hollywood comedy — which, on paper, it could very well pass as — she’d quickly turn in her notice, pack up her things, return home, and reconnect with her father. But it isn’t – in this respect, Toni Erdmann couldn’t feel more German – and as Ade has made abundantly clear in each of her features, she’s not the least bit interested in such neat conclusions — even though, at a few moments throughout Toni Erdmann, she seems to enjoy fooling the viewer into momentarily thinking that she’s moving in that direction. Ines’ trajectory will be long and painful and far from resolved by the end of the film.

It will also be immensely rewarding to witness, and Ade makes sure to gift Ines with moments of transcendent catharsis so as to prevent her film from deteriorating into a depressing wallow in the miseries of contemporary life. Ines’ ferocious rendition of Whitney Houston’s “The Greatest Love of All” and a spontaneous nude birthday party – the two scenes that provoked the auditorium to explode into raptured applause during the press screening – wonderfully evoke Ines’ suffering and simultaneously affirm her struggle. They also represent an exemplary harnessing of cinema’s full potential to bring viewer and character into a state of mutual ecstasy.

All this exalted praise notwithstanding, Toni Erdmann is not immaculate. The masquerade conceit sometimes strains belief, coming dangerously close to slipping into cheesy territory. There is a redundant and somewhat token attempt at social commentary by juxtaposing Ines and her colleagues’ moneyed lifestyle / callously capitalistic profession with the dire economic reality of the common Romanian people. This dimension — as well as minor and unnecessary subplots, such as the one involving Winfried’s mother — could have been left out to shave off some of the excessive 162-minute running time.

And yet the film is nevertheless a masterpiece, as the sheer breadth and extent of its emotional impact more than compensate for these weaknesses. In the end, even diamonds have flaws, and as far as cinematic ones go, Toni Erdmann is dazzling.

Toni Erdmann premiered at the Cannes Film Festival and will be released on December 25. See our coverage below.