With each new film, Michel Gondry falls further and further away from his Charlie Kaufman-scripted opus, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind. Here in Cannes with his new, chamber movie of sorts, The We and the I, the filmmaker continues a creative decline that appears to have no bottom.

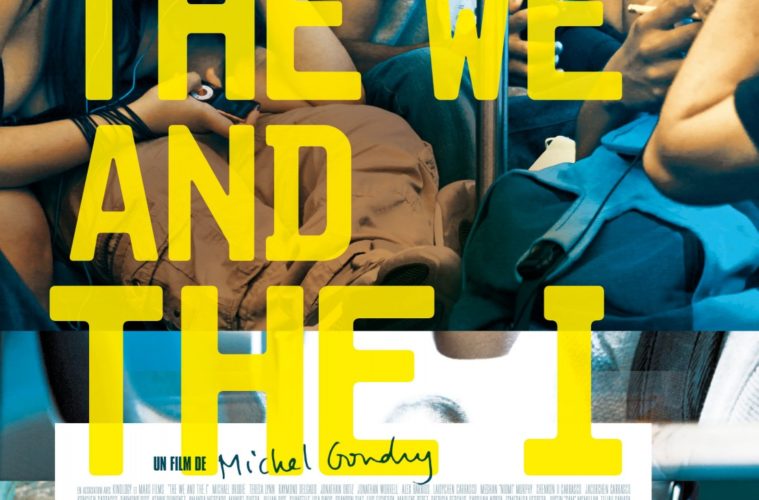

The entirety of this tale takes place on a public bus in the New York City borough of the Bronx. For the majority of those on said bus, it’s the ride home after the last day of school. We’re introduced to these high-schoolers in what Gondry deems “Part 1: The Bullies,” as we watch the cool kids on the back of the bus pull pranks on everyone from an old white lady sitting next to them to their fellow, nerdier classmates. There will be two more parts, “Part 2: The Chaos and “Part 3: The I.”

These are not likable characters, and it is admittedly brave of Gondry to attempt and portray these 15 and 16-year olds in an honest, unflattering light. The problem resides in the constant, overbearing, profound lack of balance that permeates the narrative. Scene of brutal unkindness are played for laughs, while some of the softer, dramatic moments feel stilted and fabricated. Gondry seems unable to control the tone of his film.

As the camera moves to the front and the back of the bus, we never get a clear sense of who any of these characters are and why we should care about them. Following The Green Hornet – a big budget debacle of epic proportions – Gondry seems to be spinning his wheels here, searching for an authenticity in these Bronx school kids he simply cannot find.

The intended stand-out is Michael (Michael Brodie), and the performance warrants due notice. This is a fully-developed character that emerges all too late in the game. Had Gondry put his Michael at the center of his proceedings, this could have been a stronger, simpler film. Instead, we are left more curious than invested in Michael until it’s far too late. Add to that a thinly-detailed digital aside involving a tortured teen named Elijah. We are shown a silly, YouTube-style video of him slipping and falling in his kitchen over and over and over again along with a select few other micro clips that are meant to look shot on a cell phone.

Not unlike the rest of the film, Gondry and his writing team, comprised of himself, Paul Proch and Jeff Grimshaw, seem to believe repetition is akin to character depth. Too much does Gondry’s rough-yet-flowery digital style get in the way of what might have been an interesting, fly-on-the-bus observation of these non-professional actors interacting in real ways.

What’s most aggravating is that this is an interesting idea in the hands of an interesting artist, featuring a rather original setting that would appear ripe for this type of kinetic shooting and editing. How souls, young and old, act in a crowd and then by themselves is a fascinating, relatable conceit that deserves proper exploration. Sadly, like most of Gondry’s irritatingly auteur-istic recent work, there is too much I, and not quite enough We.