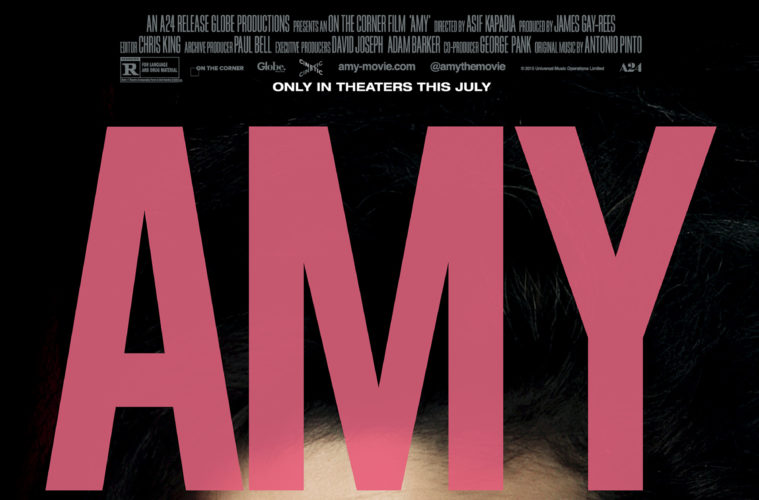

Asif Kapadia came onto most cinematic radars in 2010 with his BAFTA award winning Senna, a terrific documentary on the life and tragic death of Formula 1 race car driver Ayrton Senna. The subject matter of his follow-up documentary doesn’t seem, at first, to be a million miles away. Amy, which screened out of competition in Cannes, follows the meteoric rise and tragic fall of the late singer Amy Winehouse. It is a devastating, infuriating and sometimes breathtaking watch, and through his remarkable editing, Kapadia finds some startling truths lurking behind all the music, tabloids and nonsense.

We open on grainy home video. Two mates in 90’s clobber are having a laugh as a 14-year-old Amy Winehouse sings happy birthday to one of them, and we hear that soulful howl as if it were the first time. From here we follow her steep ascension from a somewhat tough upbringing in Essex; her first gigs on the road; catching the public’s ear with her jazzy debut Frank; before the world conquering, suffocating success of Rehab and Back to Black, the singer’s commercial peak before the dreadful fall.

It can be tricky sometimes to detect a director’s level of input on such things. Brett Morgen’s recent Cobain documentary Montage of Heck was enjoyable largely for the stash of unseen footage, and getting to hear Nirvana on a cinema speaker system. But Kapadia has shown he is a master in the editing room, piecing together a story using only footage from the time, without the usual roll call of talking heads, charts, graphics and so on.

With Amy he delves into an Aladdin’s cave of home videos, voicemails and camera phone footage, undercut with interviews with the people who had been closest to her throughout her life: her best friend Juliette Ashby, her old friend and manager Nick Shymansky, her loving if naïve father Mitch and her consciously trendy enabler boyfriend Blake Fielder Civil. Through his editing, the director attempts to uncover who might have been most at fault for the singer dying of alcohol poisoning at just 27 years of age. Mitch takes the blunt more than anyone, perhaps, having run out on the family when she was a kid and telling her she didn’t need rehab at a crucial moment in her life. There’s no doubting he’s being thrown under the bus and in the last few weeks he’s been understandably vocal about it.

Perhaps the film’s strongest aspect is that it suggests that with every redtop sold, website clicked on, and cheap gag at her expense, in a way we were all at fault. And there’s something in there, about our cold blameless relationships with screens. What film critic David Thomson once called watching — our role as the voyeur continues even as we watch the film itself. It hasn’t stopped; we’re still the voyeurs; still watching Amy. These concerns hit home in the final act when we encounter the sheer mass of footage on offer. At one point we see a little twist play out as Amy leaves a London establishment, not on video or camera phone, but in a rapid fire set of paparazzi photographs, played as motion picture; the relentless take, take, take of life in the public eye.

These final scenes are overwhelming, with voicemails from the singer offering the most fragile fleeting link with the past. Indeed, there was many a damp eye as the credits rolled in The Buñuel Theatre at Cannes. This is tragedy after all, but it wouldn’t work if the director hadn’t shown exactly what the world had lost. Amy Winehouse was a musician of incredible ability, character and heart; she grabbed the business by the lapels, rolled her eyes and went back to writing great songs. Of course, everyone wanted more.

Amy premiered at Cannes Film Festival and opens on July 3rd. See our coverage below.