Following The Film Stage’s collective top 50 films of 2025, as part of our year-end coverage, our contributors are sharing their personal top 10 lists.

It currently feels like I open every end-of-year roundup lamenting the death of cinema, film criticism, or both. And there are reasons to be pessimistic about both; you already know about the corporate mergers which threaten to wipe theaters out entirely, and if you’ve spent any time on social media, you’ll also be aware that critics are once again being declared as soon-to-be-irrelevant by the masses for things as innocuous as not putting specific movies in their top 10 lists. Same old story, different year.

2025 isn’t going to be considered a vintage year for cinema, and yet, beneath the extinctionist doom and gloom, there are far more obvious signs the art form is alive and well than ever. The film generating online backlash towards any critic who dares to not label it one of the year’s best is a genre-defying vampire period drama that couldn’t be accused of having its edges sanded down through studio interference or test audiences. Its parent studio, currently weighing up which dark side to integrate with, has seemingly caught wind of the risk aversion from their competitors and thrown blockbuster budgets at idiosyncratic auteurs – a high-risk strategy which has paid off with many of the best studio movies in years. At a glance, it feels less like the final hurrah for Hollywood so much as an unprecedented period of creativity in American cinema, a feeling only backed up by an embarrassment of riches from independent studios. And that’s just one country. We might take the piss out of NEON and MUBI for buying the rights to every film fresh off their festival premieres, but it has resulted in end-of-year prestige seasons that no longer feel like homework––the “awards bait” movies that clog up the final quarter of any year are slowly getting replaced in the cultural consciousness by the exciting international films that won’t just disappear from the conversation altogether once the Oscars have been handed out.

The movies getting awards attention are better than ever, which simply means that the ones that sadly get overlooked are only getting better too; you’ll find plenty of both categories below. No matter how much David Zaslav and Ted Sarandos try, there are plenty of reasons to be excited about the future of the artform––it can’t help but feel like the modern New Hollywood movement might have already begun, buried right under our noses while we’ve been distracted by pessimistic headlines. And if you don’t agree with me and think I’m naive, then let me offer 15 reasons to change your mind.

Honorable mentions: Black Bag, Bring Her Back, Cloud, It Was Just an Accident, The Secret Agent

10. The Mastermind (Kelly Reichardt)

Kelly Reichardt specializes in the “anti”-genre movie. After prior excursions inverting western and thriller formulas, she returned to the heightened world of the thriller following several gentler character studies in the interim to offer her offbeat take on an art gallery heist. Known for their meticulous plotting, Reichardt twisted expectations – and angered many AMC Screen Unseen attendees unfamiliar with her work––by having Josh O’Connor’s aimless protagonist operate without any sense of a bigger picture, making up his getaway scheme as he went along with zero urgency. Set against the backdrop of Vietnam war protests, her lived-in period piece still packed topical urgency as a portrait of a clueless grifter out-of-step with a moment of complete cultural upheaval. But let’s be honest––it resonated even more as Reichardt’s purest comedy, a bone-dry satire that builds into one hell of a final, cruel punchline.

9. Blue Moon (Richard Linklater)

Richard Linklater has gifted us two very different portraits of ingenious but insufferable artists this year, and whilst I was charmed by Nouvelle Vague, I never felt it overcame the accusations of cinephile fan fiction. Perhaps it’s because I’ve got no personal connection to the works of Hart and Rogers that I could overlook the creeping biopic trappings that linger in Blue Moon, even if it is far closer in spirit to Linklater’s brand of shaggy-dog hangout movie. It’s more likely that it’s because Ethan Hawke’s performance is so commanding – undeniable in the way Lorenz Hart wishes he still was to the changing face of Broadway around him – that this gentle character study feels like a 1970s New Hollywood thriller about an abrasive figure coming to terms with the sum of their bad decisions. 2025 has had more than its fair share of anxiety-inducing cinema; this is the most unexpected addition to that canon.

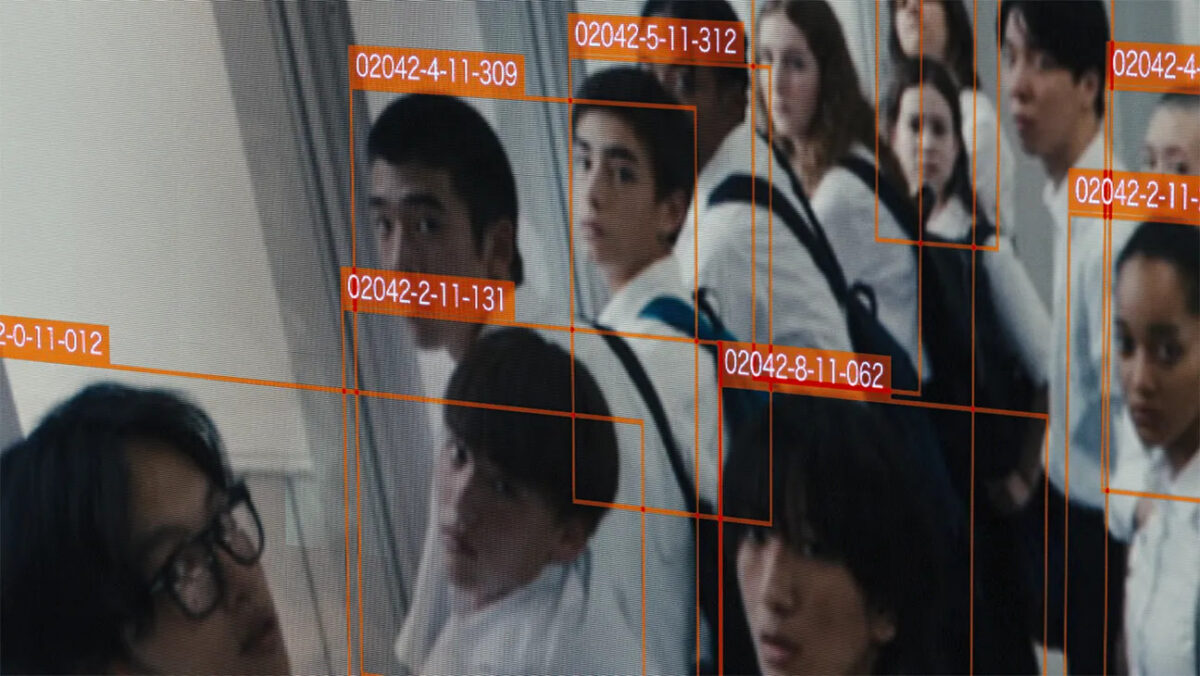

8. Happyend (Neo Sora)

We’re living through what must be a uniquely shitty time to be a teenager, but few coming-of-age movies––if any!––grapple with the realities of growing up in a mundane dystopia. Director Neo Sora’s Happyend is set in a near-future Tokyo, but it feels indistinguishable from the now, following how a friendship group slowly grows apart during their final year of high school after an ill-advised prank leads to more creeping bureaucracy in their lives. It’s an extension of an authoritarian government we see infrequently in background news broadcasts, but is keenly felt without leaning too heavily on world-building exposition––their increased alienation says everything we need to know. I won’t be surprised if this soon gets rediscovered as a prophetic modern classic.

7. Kontinental ’25 (Radu Jude)

It’s Radu Jude’s world––we’re just living in it. After the news that a Dracula theme park was being built in Romania, announced with an entirely AI-generated video no less, his status as the most plugged-in filmmaker remained secure despite his unruly, three-hour piss-take of a Dracula movie wearing out its welcome long before the midpoint. That headline-grabbing stunt diverted attention from his far more accomplished work this year; Berlinale prize-winner Kontinental ‘25, the most straightforward character drama/socio-political critique he’s made through his recent period of restless creativity. Admittedly, that’s because it hasn’t yet opened in the U.S.–– as a U.K.-based critic writing for a US.. site, I am bending release date eligibility to my will every single year––but I suspect in the new year this will still play like a quietly transformational movie for one of the most exciting auteurs currently working. This is a coherent, non-scattershot critique of Romania’s housing crisis and the parts everybody has to play in it, which doesn’t sacrifice his biting, lowbrow sense of humor to get its point across. It’s the first Radu Jude movie you could recommend without having to have an awkward conversation with friends afterwards––and it’s still, despite that description, an unmistakable creation from our favorite Romanian rabble rouser.

6. Sinners (Ryan Coogler)

Reading back my initial Film Stage review of Sinners from April, it looks like I’m pre-emptively on the defense, assuming that Ryan Coogler’s unholy hybrid of period drama, vampiric horror, and putting-on-a-show musical would be greeted with a polarized response. I’ve never been more grateful to be wrong––what felt like one of the last studio big swings was immediately championed as the breath of fresh air audiences had been starved of once they got to see it. For Coogler, it marks his elevation to the Peele and Nolan level of studio auteur. Let’s hope Black Panther 3 marks his last foray into the franchise trenches––he’s far too interesting to be given anything less than complete creative freedom.

5. No Other Choice (Park Chan-wook)

Prior to the release of Parasite, Bong Joon-ho was quoted multiple times saying he didn’t think his film would translate, likely because it was a contemporary riff on The Housemaid––he was immediately proven wrong when he realized nothing was more universal than life under late capitalism. In adapting the Donald Westlake novel The Ax, his friend Park Chan-wook has managed to make the rare modern class-climber story in which the audience couldn’t possibly take the hero’s side. This is a bloody-and-hilarious work worthy of Joseph Losey and Harold Pinter, with the satirical bite only sharpened as the struggles we’re seeing are entirely of the first-world variety––a guy who has it better than us even *after* being made redundant convinced he’s suffering more than most. Park has long been skeptical of the upper middle-classes, but this is his most scathing work yet.

4. Marty Supreme (Josh Safdie)

It would be easy to accuse Josh Safdie of making the same movie for the third time in a row. After Good Time and Uncut Gems saw him gravitate away from murkily realist dispatches from New York’s margins to intense dark comedies about men who can’t help but see their lives as one long gamble, Marty Supreme explodes this well-established formula onto a broader, gorgeously realized period canvas. This alone would be enough to establish his first effort as a solo director as another reliably anxiety-inducing spectacle worth the six-year-wait, but this is a far richer text than its predecessors. Safdie twists the inspirational underdog sports tale on its head to make it the stuff of nightmares, all while exploring weightier themes like post-war Jewish identity, US-Japanese relations, and the changing face of American mythmaking. It never feels tied to its 1950s setting despite this; a never-better Timothee Chalamet plays an antihero who manages to embody the moral emptiness of contemporary #Grindset culture even without a single foot in the present. It’s no exaggeration to call this character Gen-Z’s Jordan Belfort, and Chalamet’s performance a worthy successor to DiCaprio’s career peak.

3. Resurrection (Bi Gan)

The day I saw Resurrection, an interview quote from none other than George Miller was doing the rounds, with the Aussie auteur declaring that AI was “here to stay,” and that it would lead to an “egalitarian” evolution in filmmaking. Setting aside that I only want talented people making movies and not just any Bozo with an internet connection, it was a quote that was conclusively proved wrong the second I saw Bi Gan’s third movie. Sure, some AI software could approximate different genres and styles spanning more than a century of cinema, but it could never feel like anything more than a soulless exercise. The Chinese wunderkind’s latest, most head-spinningly ambitious effort to date is a journey through the medium’s history loosely disguised as high-concept sci-fi, opening with a gorgeously crafted silent film pastiche and culminating with a single-take vampire romance. It’s a whistlestop tour of the Chinese 20th century, but one which defies all categorization and explanation in the moment––pure cinema designed to be felt, not thought. No machine could ever compete.

2. Sirāt (Oliver Laxe)

Oliver Laxe hasn’t been shy about Sirāt being the first film he’s made with a larger audience in mind, his invitation to the masses to join him on an intense spiritual journey that more than deserves its title as The Wages of Fear’s mythic successor. What is less discussed is that his film is an anti-crowd-pleaser for the ages: a movie that demands to be seen on the big screen like few others this year, even if the emotional extremities of its second half feel designed to make an audience run for the exits. When watched with a packed crowd, the gasps you’ll hear are as relentless as the sound design––it still proves impossible to look away from such an uncompromising vision of hell on earth. No matter when you see it, if it’s on the big screen, it’ll wind up as one of your most memorable theater experiences of the decade.

1. One Battle After Another (Paul Thomas Anderson)

A critic’s top ten list with One Battle After Another at number one? Groundbreaking. And yet, I’m not even certain PTA’s latest will break into my top five favorites from him, which is saying something. I left my VistaVision screening exhilarated from that climactic car chase, on the verge of tears at the evolution of the core father-daughter relationship (the most nakedly emotional Anderson has allowed himself to be since Magnolia), and with a voice hoarse from laughing like a maniac for much of the preceding three hours. So many throwaway lines have entered my everyday vernacular––Bob’s “We’re talking about freedom, baby!” is a current favorite––so many character gestures right down to their very walks etched onto my brain, with the whole ensemble now at the forefront of my mind as the physical comedy performances I measure all others against. Few directors can pull off just one of these aspects in their definitive work; my sixth favorite PTA movie is miles ahead of everybody else’s career best.