There’s a lot of drinking, snorting, sucking and crying throughout Mark Pellington’s I Melt With You, a two-hour rock-n-roll meditation on the middle-aged white man sadly burdened by plot just at the moment pure abstraction is the only road to take.

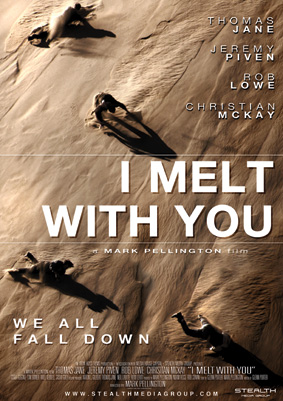

Opening with a slew of general declarations thrown at the screen in white text over black, (‘I hate myself,’ ‘I’m not a good lover,’ etc.) it’s clear how singular the movie will be. Pellington’s venting here, and he’s not ashamed about it one bit. The film stars Rob Lowe, Thomas Jane, Jeremy Piven and Christian McKay as four 44-year olds disappointed they never became what they thought they would be.

Sound familiar? Of course it does. Thankfully, it doesn’t look familiar. The four old friends retire to the coast for a week-long birthday celebration for Tim (McKay), who’s bent up about something (spoiler alert: they all are). The camera can barely stay still for second, jumping from canted angle to canted angle, Pellington digging into his kinetic, music video roots. Not surprisingly, there’s not a boring shot in the film. From steadi-cammed close-ups to crane-caught wide exposition shots, Pellington and his cinematographer Eric Schmidt are all over the place. Any kind of narrative continuity is non-existent.

Throughout the first half of the film (and some of the second), Pellington blares punk rock so loud the dialogue is barely audible. At one point, subtitles are utilized. This isn’t as burdensome as it sounds, as Glenn Porter‘s screenplay proves to be the film’s weakest link. Our leads stumble around their thoughts rather eloquently for a bit, most notably in a scene between Piven’s Ron and Jane’s Richard. Ron attempts to confide in Richard, who scampers off from the honesty like a scared puppy.

At some point, however, the men will have to face their feelings, and when they must they do so a bit too directly. Some things are better left unsaid. Pellington doesn’t give us much time to react, switching the track and finding another frame to obstruct.

Piven stands out among the rest, opening as Ari Gold and then stripping himself down to the bone. His Ron drowns in front of our eyes, with twitching eyes and quivering lips to boot. All four acting vets give their all here, going so far in one direction the whole experience becomes more like performance art than anything else. It’s at this point the stilted dialogue feels somewhat intentional, purposefully cliche as further illustration of the vapid vessels these four men really are.

This is what Pellington wants. These are all despicable, pathetic man-children too busy complaining about themselves to do anything about those things that bother them. Because of this all of those around them suffer, and they only seem to care when they’re high out of their mind. It’s hard to sympathize with this kind of honesty, but hard not to appreciate. Lowe, unfortunately, brings up the rear with a glossy performance that never reaches the nuanced levels of his three counterparts.

In the middle of what would be the second act was there any act structure at all, the film takes two, opposing turns: one into pure moral madness, the other into cardboard-cutout plotting. The former follows suit with the rest of the film, the latter involves Carla Gugino as a local cop “hot on the trail” of these out-of-towners. This strange departure comes complete with a throwaway conversation between Gugino and another woman friend about the fractured-psyche of the male. It feels, and is, pandering to the opposite sex the rest of the film so blatantly disregards.

Auteur filmmaking divides far more than it conquers, and Pellington’s mid-life crisis will most likely live its life shouting to an empty room. But this kind of daring, bravura filmmaking must be appreciated: a flawed work of art that will start conversations that’s sure to include the question, what was Pellington thinking? That’s the kind of interest, good or bad, that keeps daring pieces like this alive while “better,” safer films fall to the wayside.

What makes art good or bad? How personal is too personal?