“Boys and girls in America have such a sad time together.” That line is left out of Walter Salles’ adaptation of Jack Kerouac’s On The Road, but it permeates every scene. Most of the film’s conflicts arise from how playboy Dean Moriarty (Garrett Hedlund) is going to balance Marylou (Kristen Stewart) and Camille (Kirsten Dunst), as he and Sal Paradise (Sam Riley) never seem to be in too much trouble, despite always having enough money. Like the book, it’s bound to be criticized for misogyny and homophobia, but its depictions are scarcely endorsements. On The Road is more a story of a lifestyle and all the pitfalls and glories that come with it than a longing for the culture that accompanies it.

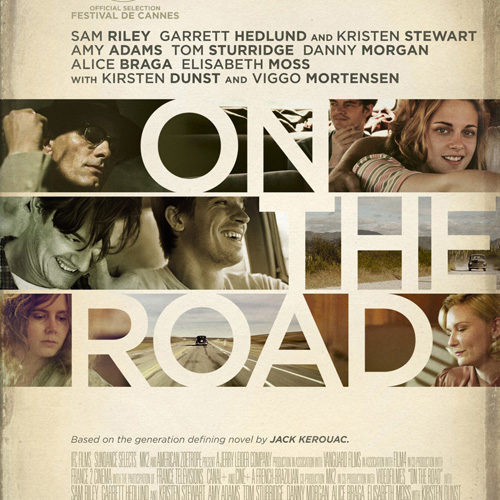

Even if you have never read On The Road, you probably know the story. The Beat Generation, with fictionalized names, goes around the country trading intellectual banter, having sex with men, women, and possibly each other, doing drugs, and going broke. In this version, Sal (Jack Kerouac’s stand-in) is the story, but Dean is the plot. Hedlund resembles a young Brad Pitt in both appearance and acting style. He secretes a toxic charisma that brings hopelessly romantic women and longingly curious men no matter what sins he commits. Dean is a sleaze in every sense of the word, but for some reason, perhaps because we see him through the eyes of Sal instead of the women he torments, he remains likable.

Where’s the conflict? Well, there isn’t one really. There are a few shouting matches, but On The Road resembles a grittier, if less realistic, early Jim Jarmusch film, never quite making clear the motivation, but still attempting to deconstruct somebody’s vision of the American Dream. The only link that gives more than a surface explanation for the brotherhood between Dean and Sal is that both are looking for a father. In Dean’s case, it really is his father, who disappeared some time ago. Sal needs a surrogate; his father dies just before the film picks up, and if he ever seems over it it’s only because it isn’t shown to affect him often enough. Instead, the film is littered with tributes to the Beat Generation: Ginsberg’s poems show up in fragments, passages by Burroughs recur and for all the havoc these men cause, all the depression and loneliness they seem to exhibit, they are never punished for it. It’s a chronicle of an endless road trip that strikes a tonal balance between romanticized and realistic that makes every scene a pleasure.

Most of this is not the fault of screenwriter Jose Rivera (he was nominated for an Oscar on his previous collaboration with Salles, The Motorcycle Diaries), who combined the original scroll and the book with his own aesthetics and Beat tributes to create an original and cinematic template. On The Road was full of misogyny and homophobia; Rivera tried to correct that. His Marylou is dying to be portrayed with complexity; it is only Stewart who turns her into a flat caricature. Camille, particularly in her final scene, reveals herself to have more personality than we would initially presume. Most of all, Moriarty is a vehicle of destruction and selfishness begging to be analyzed, with a slew of thematic possibilities dying to be explored.

Salles, however, never lives up to his end of the bargain, rarely letting his actors bring out a full character and free from unlocking any subtext. For all the versatile cinematography, varied locations and jazz music, On The Road is far more interested in period creation than in providing commentary or invoking universality. These elements, while well-executed on their own, never come together. It’s one good part of a scene or one good scene all strung together with little to say — at times, that works. Hedlund’s charisma is enough to keep watching, and Rivera’s screenplay is sharp and spontaneous, broken up by narrative passages that never make the mistake of telling us what we have seen. It’s through these passages that we get to know Sal. Too often, however, it does not work as Riley cannot keep up with Hedlund, so Sal never grows onscreen, he just waits for epiphany.

On The Road wanders aimlessly, and that’s the point. That it wanders aimlessly but does not say enough about the wanderers or about wandering is the problem. Like the characters it depicts, On The Road is about the journey. You know there is not much to learn at the end, but it provides a good time getting there. There’s enough visual flair and more than enough humor to get you there. But ultimately, Salles never gives us a chance to take from this journey what Sal Paradise and Jack Kerouac did, and he cannot claim that he never had a chance.

On the Road hits limited release and VOD on Friday, December 21st.