Migration isn’t just a hot-button issue in the political arena. It’s a hot topic in your local arthouse theater, too. At Berlin’s film festival, the subject is everywhere–from Wolfgang Fischer’s Styx and documentaries like Central Airport THF–perhaps natural for the capital of a country now home to more than a million recent asylum-seekers from the middle east and Africa.

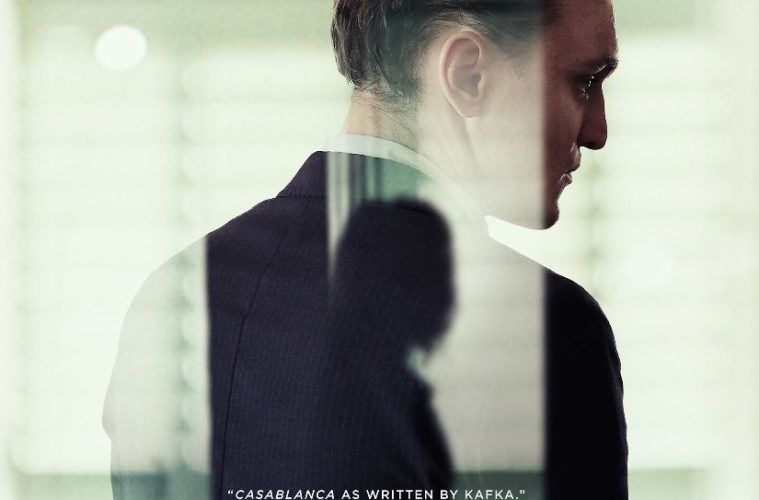

Local boy Christian Petzold’s audacious retelling of Anna Seghers’s World War II-set novel about refugees escaping Nazi-controlled France is a strange, beguiling creation that will be hard to beat in the competition line-up, and ranks as a rare period piece that utterly gets under the skin of contemporary concerns. It’s an engrossing, uncanny and somewhat disturbing film, and completes something of a trio of historical melodramas after Barbara and his worldwide hit Phoenix, but develops the themes of those in an adventurous, if oblique, way.

If those two films had narratives that constrained for neatness, Petzold’s methods prove more of a challenge in Transit. Here character like war-scarred Georg (Franz Rogowski, lately of Happy End and Victoria) wear period dress but roam around modern-day Marseille, with its high-rise developments and tourist-friendly vistas. The effect is disorientating–ghosts of the past are ever-present in modern Europe–and without a doubt emphasizes how little has changed about the situation for migrants in the seventy years since the Second World War. Eagle-eyed cineastes might recognize this from films like Alejandro Jodorowsky’s Endless Poetry, but while that reflects on autobiographical history, Petzold’s wider canvas searches for grander comparisons, perhaps that European migration in the 1930s and 1940s should affect the discussion that still rages in the EU of today.

Petzold, without regular muse Nina Hoss for the first time since 2005’s Ghosts, instead centers on Georg, an escapee of a concentration camp who flees Paris just as the Nazis march in. With him are visa papers of a once-great communist writer who slit his wrists to avoid capture by the fascists. In a split-second decision Georg takes up the identity of the late writer (a curious reversal of the plot of Phoenix), and the film explores the last few weeks he spends French port city of Marseille before his final trip out of the continent.

Only those who can prove they will leave may remain in Marseille, a purgatorial contract that means Georg and his fellow travelers are ephemeral figures in the life of the city, neither there nor absent. “You don’t exist in their world,” Georg suggests. He can only befriend fellow illegal residents in the migrant ghetto, such as a family from the Mahgreb, also looking for an escape, whose presence blurs the line evermore between the past and post-colonial 21st-century France. But Transit also concerns the psychology of migration, with Georg and others’ desperation to cling onto what they leave behind. A love triangle forms between Georg, Jewish doctor Richard (Godehard Giese), and the mysterious Marie (Paula Beer), as Petzold swerves from Holocaust drama to noir-ish psychological thriller.

As the Germans march closer, cleansing each city they takeover of undesirables (“spring cleaning,” one refugee grimly puts it), Petzold’s characters are able to capture a rising dread, a tragic posture as if they know even if they get through this terror, the psychological scars will last. And not just from what they witness; more than that, there will be a shame just to survive as so many others are whisked away. Those who’ve seen East Germany-set Barbara may anticipate the conclusion of Georg’s visa story.

The setting in Marseille, one of modern-day Europe’s most visibly multicultural cities, means to compare it with Europe’s current migrant crisis, which is inevitable. (Though to use the term “crisis” might be a Fox News-ification of facts–more than a million Syrians have settled in Europe since 2014 with varying levels of ease.) More than inevitable, it’s essential, because although Transit tells the story about emigration, really, it’s about immigration, and how society cruelly dehumanizes and desensitizes us to the tragedy of refugees. Too, it’s about placelessness, being constantly in transit, trying to imagine the lives of those for whom home is a word that has no meaning. And it’s about history, and how the cliché rings true that those who cannot learn from history will repeat it. This is a richly rewarding film, packed with ideas and riddles, that will surely benefit from repeat viewings.

Transit premiered at the Berlin International Film Festival and opens on March 1, 2019.