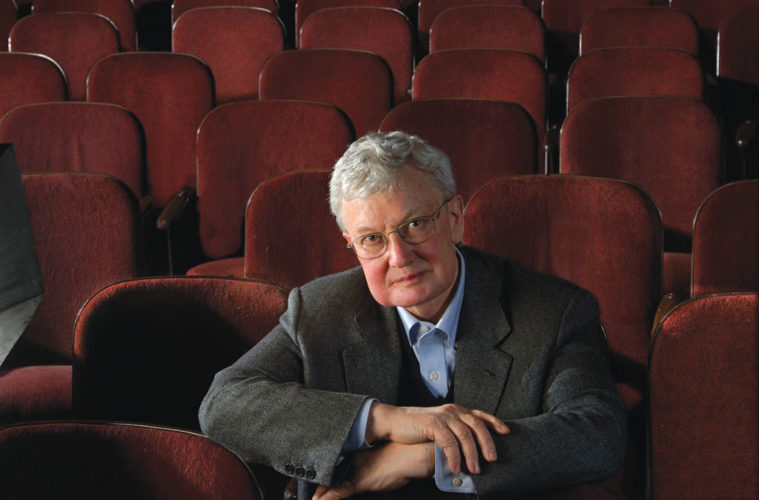

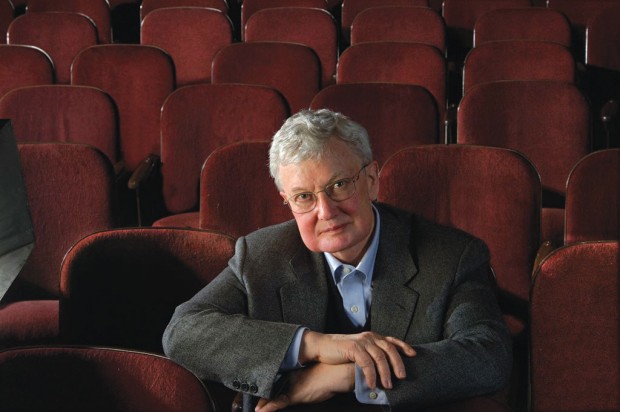

The face of American film criticism has died. Roger Ebert, according to the Chicago Sun-Times, has finally lost his long-gestating battle with cancer at the age of 70. Ebert’s latest blog post, published a mere two days ago, suggested a weathered man — he officially declared “a leave of presence” from his regular duties as film critic for the Chicago paper — but not a defeated one. He expressed the many plans he had for the near future: to revamp his much-visited website, RogerEbert.com; to continue fostering the careers of young critics, like fellow Chicagoan Ignatiy Vishnevetsky, who’s now a template of Internet-aged film criticism thanks to Ebert’s helping hand; and to assist Steve James in adapting Life Itself, Ebert’s 2012 memoir, into a feature-length documentary.

These are not ambitions a man nearing death would normally publicize, but the blog post is emblematic of the type of figure Ebert has developed into during the 21st century. In theory, the inability to speak would be nothing short of crushing for someone like Ebert, who catapulted to a new level of fame and power through the very medium of television. Though Ebert had been working in the film-criticism field full-time since 1967, it wasn’t until his debates with the dryly energetic and intelligent Gene Siskel that he grew into a larger-than-life figure, an atypical celebrity of great wisdom and knowledge.

See Also: A Dedication to the Life of Roger Ebert

The way he responded to his health troubles not only confirmed his singularity, but also further transformed him into a beautiful hybrid of studied academic and personal memoirist. Forever sketched into my mind are the descriptions he wrote about his time at the University of Illinois, where he’d walk down grassy paths and see students reading Shakespeare under a tree. Equally vivid are his heyday recollections of working in an actual newspaper office, where people smoked cigarettes and chatted intensely as they hammered out their stories. I’ll never forget his history with alcoholism, either: to read his reviews of films like Leaving Las Vegas, Crazy Heart, and other similarly-themed works is to be warmly invited into an individual’s worldview with a level of intimacy that is astonishingly rare within the field of film criticism.

These personal revelations weren’t only written about in his reviews, but on his blog as well, where he frequently reminisced about certain family members, friends, and mentor figures. As Ebert got better and better at writing in this format — not to mention how perfectly he molded himself into the Twitter fold — it became clear that he was as gifted and affecting a writer as he was a surveyor of the movies. He could write as eloquently about a bar he used to frequent as he could about a climactic moment in an Alfred Hitchcock classic. In his later years, Roger Ebert knew no limits, and this freedom gave birth to some of the richest, most vulnerable work of his whole career.

In this sense, there are two remarkable phases to Ebert’s career: the print-and-television celebrity of his earlier years, and the Internet-based celebrity of his later ones. That he made the transition so seamlessly doesn’t fully do justice to the achievement. What it essentially means is that Ebert’s work has appealed to multiple generations — to young and old film-lovers alike — and that the level of humor, insight, and clarity in his work has the ability to successfully navigate the obstacles of time. At the risk of momentarily edging this piece into personal territory, I can say that the first thing I always do after watching a movie is read Roger Ebert’s review, and it’s a comfort to know that there are still reviews of his that I haven’t yet read — reviews that will be there forever.

Like all great artists, the passing of Ebert carries a momentary shock (I probably shouldn’t mention this, but I left class to reminisce and work on this brief obit), but it’s one that can be dealt with in a very positive light, considering the vast amount of work he leaves behind. Reading some of the things that have already been written about Ebert today, the number that continues to shock me is 70. How in the world was this man only 70? From the weekly reviews to the blog posts, from the memoirs to his perfectly pitched “Great Movies” series, from the TV-show appearances to his digital-media mastery, Ebert’s résumé simply makes everyone else’s seem part-time. This is a man who will never cease to be a part of our ongoing conversation about the movies. And, judging from the immediate response to his passing, he’ll be just as crucial a part of our discussions about life in general as well.