Though always prolific as a playwright, Neil LaBute’s past decade at the movies has been filled by studio pictures which never quite found the creative success of earlier works In the Company of Men or The Shape of Things. However, hot on the heels of his first original work since (Some Velvet Morning) a new adaptation of his 2005 play Some Girl(s) appears to be bringing the man back to his roots.

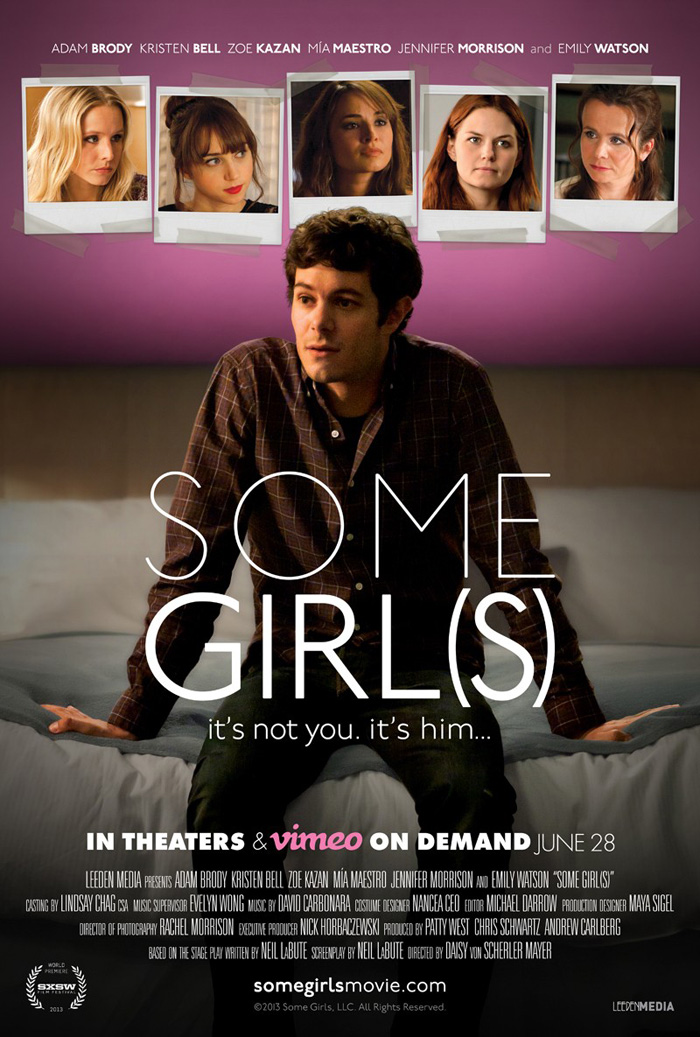

Directed by Daisy von Scherler Mayer, the film depicts a young man (Adam Brody) traveling the country to “right the wrongs” he may have committed with a few ex-girlfriends before getting married.It consists of intimate one-room segments chock full of the auteur’s trademark dark wit, as well as emotionally heavy performances from a mostly female ensemble. With a full plate bringing the debut of a new play at the MCC Theater and pre-production on the next cinematic endeavor to write and direct, the gracious LaBute found time to tell us about the process of adapting Some Girl(s), handing scripts off for other artists to direct, and his approach to writing.

The Film Stage: It’s been ten years since one of your plays made it to the big screen.

Neil LaBute: Yes.

So I was wondering if you could talk about the journey Some Girl(s) took? Were you a driving force behind it?

I wasn’t, really; it wasn’t one I thought about adapting or anything. The producers did come to me and asked about putting that on the screen, and I thought, “Great.” I’ll help in the adaptation and everything, but it was not an idea I had originally had.

Actually, at some point you think about all of them — you know, in some way. But, not very realistically, you kind of go, “Oh, would that be a good movie or not?” Some just feel completely [like they couldn’t], but this one — it had the elements of a road picture. But on stage, of course, part of the fun is keeping the same set and just changing enough elements to make it feel as if people moved to another very corporate kind of hotel. So, here, they took the drive and initiative to show part of that journey and make it feel opened up in some way — as in beholden to the idea of a movie. But, overall…

And then we included the fifth woman, who wasn’t in the main stage versions in London or New York or Los Angeles — and, then, that material was added, so we had to trim everything down a bit to make all the women fit. But, overall, that was my contribution: the original text, but also a bit of adaptation. But, in terms of the production, they were the driving force behind it.

You didn’t direct the original London or New York runs.

I didn’t. I did Los Angeles.

Do you find it appealing to see what different directors will do with your text, or are you still hands-on during production?

No, no. I think it’s great. I’ve done a lot of that in the theater, certainly, and this is one of the first examples [of that] for film. I’ve directed other people’s stuff and / or my own, but on-stage I’ve had a lot of people direct my stuff, so that’s always been something I was comfortable with. And I think having a woman do it was an interesting idea, and that is part of the fun: seeing one director in London, and one in New York, and then myself in Los Angeles, and then this version.

And there have been a number of other versions elsewhere around the world. It’s fun to see what somebody will bring to it — what they’ll highlight, what they don’t spend as much time on, who they cast, and what sort of drives them and what parts are most important to them. It’s a fantastic part of theater more than film: to see the multiple takes on the same material.

And going back to Zoe Kazan’s Reggie [the added fifth character]—I know you had her published in the book but not actually performed on stage.

Right.

What changed that made you want to include her now?

Well, I had the notion about one more trip. I suppose I could make a series out of it, you know? If I could realistically say he had one hundred girlfriends then I’d get to the magic number.

But I came up with one more story and wrote that, and it ended up being published. Since then people have used it in a variety of ways. They’ve either done the original four, or some have done all five, or some have done a mix, taking one of the original ones out and putting [Reggie] in. But in this case [the producers] wanted to include all the women, so that really demanded bringing each of their stories down a little bit so it would fit in the time frame that made sense for a film. So there was a bit of cutting and reworking, plus the material that would carry us from city to city, so there were certain aspects that… each one had to be a bit sleeker, really to make that all click.

I think [Reggie] changes the complexity and the color of the journey because [she] wasn’t someone who he originally set out to talk to — the idea that [she] was someone he saw along the way that made him reevaluate and readjust his bearings. I think that makes [the film] that much more interesting.

Yes. And it’s interesting, too, because he tells her that he didn’t see his actions as more than a kiss, but you almost have to think he never would have called her if that were true. He must have known somewhere in his subconscious to even confront her for this conversation.

Yeah, that’s some part of it. I think it’s also the age thing: that you both may remember it differently, and who knows if the truth is somewhere between what she describes and what he describes. But she was incredibly young; she was eleven going on twelve. So, whatever happened was pretty inappropriate, and, obviously, it affected her in a certain way.

And I think you’re right. I think that he is saying, “This is what I remember.” But that could be a man who’s also being confronted and someone who doesn’t want to dig any deeper than he has to. I think that’s true of all his encounters. I think there is probably still some sense of good will here, of, “I want to try and rectify that or talk about that and make good on certain things.” But in parentheses you’d probably say, “As long as it’s not too much work or costs me anything.” He seems a little half-assed about it in terms of the way he’s [moving forward]; certainly the results are lousy. [Laughs] Every time he does it he opens old wounds or creates new ones.

And that’s kind of part of the selfish delusion: he thinks these women are archetypes like the high school sweetheart or the one who got away. But they all turn the table on him and they’re very strong female roles as a result.

I hope so. I get [shit] enough for how I feel about women — or what I write, or that kind of thing — yet I think I continue to write at least interesting women rather than people who are not. But that’s just the way it is. People like to label things, and so [misogynist] appears to be a convenient label.

The play has attracted a lot of fantastic female performers — whether the original London run, New York, or this movie. How do you approach writing the opposite sex when it seems critics love to deride men for not being able to do so?

That’s a bit of… you’re never sure. It’s a bit of a trick. You have to listen well and figure that their experiences are akin enough to yours as a human being. That you can write that and be observant, because there’s some part of it where you’re just stepping off a cliff and going, “I really can’t know what that is like.” I can understand what heartache is, but I can’t understand being pregnant or losing a child or those kinds of things.

So one of the greatest compliments you can get as a writer — male or female — is that you can write the opposite sex with any prudence. It’s always great to hear an actress or an audience member who’s a woman say, “Wow, you really are able to draw realistic portraits of women.” Because there is some part of it where you’re walking around in the dark with your hands out, going, “I hope I’m doing this right.”

And on the other end is Adam Brody in a lead role that David Schwimmer originated in London — both of whom are known for playing a somewhat harmless neurotic on TV. Do you think an audience’s connection to their characters helps allow the man from Some Girl(s) into their hearts before the final reveal crushes them?

Well, I think what they probably all share as performers… yes they’ve been characters who were liked by audiences, and people identify with television actors in a particular way. They really kind of strongly identify with them because they see them, so often, as the same character in their home. It’s a different kind of relationship. So, what Eric [McCormack, who starred in the New York staging] played was quite different from what Adam played on television, or David. All of them kind of had a boyish quality — likeability, humor — that helps people drop their guard down a little bit and want to embrace them. They think they know them as those people.

So, I think that there’s no way around the fact this helps take an audience on that journey; that’s something I’ve been doing for a long time. I work with actors who are at that place or just after they were. I’m doing it right now with Jenna Fischer from The Office [in reasons to be happy] playing a really quite foul-mouthed girl who has a very fiery temper. But she brings a kind of sweetness to it, even though she has those attributes on stage. Or Calista Flockhart at the height of her kind of girl next door /America’s sweetheart — she played a child murderer [in Bash: Latter-Day Plays]. So that’s been something I’ve kind of targeted throughout my career of taking an audience’s expectations, and subverting them, and using your actors to help you do that.

A big theme with this character is also that the women have all seen that he published an article using their experiences together. We’ve seen this idea in Woody Allen’s Deconstructing Harry and on TV in October Road—but I’ve read interviews with you that say you don’t write from your own experiences in that way. Could you speak on why that is? Are the moral implications from Some Girl(s) kind of an explanation for that?

Possibly so, but I guess it’s just that I’ve never found that to be the way in which I wrote. I either didn’t feel that my background was… or the lives of people around me were interesting enough (or mine) to use. Or whether I’m just not open enough to want to do that. I’ve always felt that my job is to tell stories — stories that are rooted in fiction and so, therefore, are going to be fiction. There’s certainly, I’m sure, pieces that someone could look at myself or probably more clearly others from the outside, going, “Oh, there’s some of you in that,” or “that reminds me of your father,” or “gosh, that feels like something that we went through when we were younger” — but I don’t blatantly and openly and consciously go, “I’m going to tell that story and now this story and now that one about my grandmother.” It’s just not the way I work.

But, yeah, on the other side of that there is totally truth in, as a writer, saying “I don’t love that.” I don’t love that notion that people look at that material as open season. That something happens and therefore it’s theirs to put out. It’s the same way I feel about that strange thing about people who just randomly like firing off pictures and going, “Oh, there’s so and so. I’m going to take a picture of them and tweet it and say whatever I want.” Property is a funny thing, and so it has a great complexity as an issue to me. So, I think that was part of what was interesting to me, to write about another kind of writer: the one that I’m not.

This character almost takes on more relevance today, too, with social media and all these things and the questioning of ownership.

Yes, there’s a lot more of that out there now, where everyone is more than happy to spill their guts in whatever media they can.

With Some Girl(s) bringing one of your plays back to film, do you have similar plans for any of your other work? I know you just wrote a sequel to reasons to be pretty [the aforementioned reasons to be happy].

Yes, I did that, and I did a film this past year that was just at Tribeca — called Some Velvet Morning — that I’m sure will be coming out some time soon. And I’m continuing to write.

And you have one going into production, called Seconds of Pleasure?

Some time soon, yeah. We keep talking about that. I’ve written a script and it’s some sort of mix between an English and American co-production, so there’s a little bit of that “how do we make it all work together,” but I hope that happens soon.

Some Girl(s) is on VOD and in limited theatrical release as of Friday, June 28.