It is strange to think that even now, in an age with seemingly infinite access to the entire world of cinema, many of our viewings are quite limited in their diversity. European cinema still dominates whatever U.S. market may even exist for foreign films — with the occasional works peppered in from Hong Kong, Iran, or Argentina — but even those appear to only fill certain boxes: while Wong Kar-wai and Abbas Kiarostami are certainly some of the most imaginative directors working today, their labels as “Hong Kong’s Godard” and “Iran’s Godard” is both a blessing and a curse. Searching out films from the far reaches of the Earth can remain somewhat laborious for those without expertise (especially when you don’t speak the language), but it is a quest that provides bountiful rewards, especially when glancing at works without any precedent in the Western world.

In the spirit of this quest, the latest Criterion box set, Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Project, Volume 1, can make good on providing a New Year’s resolution for anyone hoping to expand their filmic knowledge. (Before we move forward, in the interest of full disclosure: the UK company Masters of Cinema have released a similar box set, their iteration coming with different films and essays; I work for the company, but had no hand in producing that particular title.) The Criterion box set contains efforts from six non-Western countries: Senegal, South Korea, Morocco, Bangladesh, Mexico, and Turkey, each providing a more-than-fine start for anyone attempting to work their way toward a world cinema instead of a Western cinema. The titles contained herein, highly diverse and communicating specific cultural backgrounds, provide unique aesthetic experiences which illustrate the relationships between filmmaking modes scattered across the globe.

In the spirit of this quest, the latest Criterion box set, Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Project, Volume 1, can make good on providing a New Year’s resolution for anyone hoping to expand their filmic knowledge. (Before we move forward, in the interest of full disclosure: the UK company Masters of Cinema have released a similar box set, their iteration coming with different films and essays; I work for the company, but had no hand in producing that particular title.) The Criterion box set contains efforts from six non-Western countries: Senegal, South Korea, Morocco, Bangladesh, Mexico, and Turkey, each providing a more-than-fine start for anyone attempting to work their way toward a world cinema instead of a Western cinema. The titles contained herein, highly diverse and communicating specific cultural backgrounds, provide unique aesthetic experiences which illustrate the relationships between filmmaking modes scattered across the globe.

The history of the World Cinema Project — until recently known as the World Cinema Foundation — begins with a collaboration between two American giants: director Martin Scorsese and film critic Kent Jones, the both of whom, since 2007, are working with film archives, programmers, and filmmakers themselves to unearth the most unique works of otherwise-ignored national cinemas and restoring them in often-astonishing transfers. The foundation’s goal is, simply, to emphasize and promote cinema’s global influence. As Jones notes in his introductory essay, a foreign view of cinema through the 1970s was dominated by Ingmar Bergman, François Truffaut, and Federico Fellini — and, in moving away from titans of that particular sort, the project has emphasized filmmakers who have been revered in their own country but frequently forgotten, many a time due to the lack of international festival exposure.

I find it somewhat fitting that three of the selections in this first box set could be defined as “genre films,” or at least closer to “entertainment” than, say, something aiming for a Cannes debut. Perhaps none defines that better than Kim Ki-young’s The Housemaid, a lurid and intense psychosexual thriller from South Korea. Made in 1960, The Housemaid focuses on an affair between a husband and his family’s domestic helper, fiercely chronicled with intense tracking shots, a supremely sinister spatial design (the action is mostly confined to a single home), and a score filled with staccato beats that never leave the viewer in any place of comfort. Kim’s film was largely disregarded until having been rediscovered, at a retrospective in the ’90s, by South Korea’s then-young generation of filmmakers (e.g. Kim Ki-duk and Park Chan-wook), quickly becoming a teleological confirmation of their work in the way another 1960 film, Psycho, would serve as a cornerstone for American artists. (This is to say nothing of the two being able to fit neatly on a double bill.)

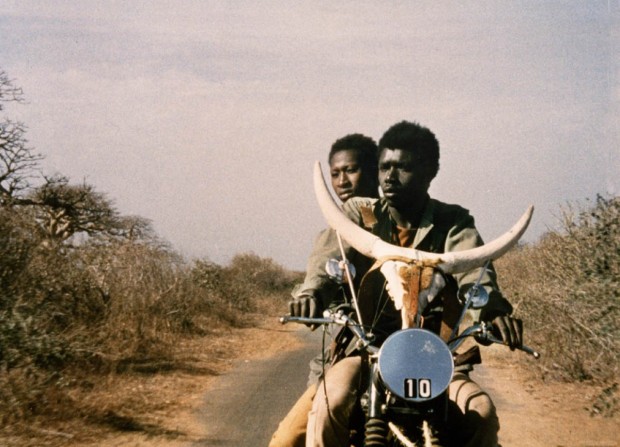

Even more fiercely radical would be the set’s selection from sub-Saharan Africa: Djibril Diop Mambéty’s Touki Bouki, a Senegalese picture. Though too easily billed as (again) “The Senegalese Godard,” Mambety’s rhythms are less pointed and more sensuous (Claire Denis has cited this title as a major influence), even if the basic plot may recall works like Pierrot le Fou and Breathless. An early sex scene between the two major characters — shot, mostly, as an off-balance composition of a hand grabbing a motorcycle while listening to the ocean crash against the cliff below — is nothing less than revelatory in its attention to a unique type of longing and desire that’s implicit to both the characters and camera itself. African cinema is a cornucopia of discovery, ranging from Senegal to Cameroon to Chad — not to mention the ever-strange practices of Nollywood — and that very discovery is a cause I’ve made known through Twitter. If the continent’s filmmaking has been easily defined by a division between explicitly political filmmakers (e.g. Senegal’s Ousmane Sembène and Mali’s Souleymane Cissé) and the so-called “village films” like those of Burkina Faso’s Idrissa Ouedraogo, Mambéty’s work somehow splits the difference, avoiding easy categorization while also being a radically fun work.

Politics is an underlying theme in many of these titles, the challenges to Western imperialism and capitalism dictating both narratives and aesthetics. It’s certainly explicit in the Russian formalist-influenced Redes, a Mexican film directed by Emilio Gómez Muriel and High Noon helmer Fred Zinnemann, though it’s perhaps less notable for a depiction of “exploitation” than its alleged realism, as exhibited when citizens from the Alvarado village show off their fishing techniques in one poetic sequence. The Moroccan documentary Trances, from Ahmed El Maânouni, highlights the band Nass El Ghiwane, whose rhythmic beats on kettle and frame drums are supplemented with pointed lyrics challenging social inequality while, too, reviving classical poetry. Maânouni finds a unique culture on the fringe of what always feels like a revolution during the band’s concerts. And even the Turkish melodrama, Dry Summer — an intensely, didactically filmed work with brutally expressive images — offers a critique of patriarchy and capitalism in a way that might make for a good double feature with, of all things, Chinatown (both involve missing water).

The hope encouraged by The World Cinema Project and this, the first of many box sets, is that one never tempers their engagement with global cinema. (Films such as The Night of Counting the Years [Egypt], Downpour [Iran], and Manila in the Claws of Light [Philippines] should make large splashes when they’re finally released.) The Housemaid offers an excellent gateway into Korean cinema from the 1960s and 1970s, but one should take the next step and dive into bountiful transfers on the Korean Film Archive’s YouTube page. Political works of North Africa are not just music documentaries, but also comedies from Algeria (Omar Gatlato) and autobiographical tales from Egypt (Alexandria… Why?). As Adrian Martin writes in his essay concerning the Bengali film A River Called Titas, “New access to important works from the past often prompts a revision of film history — especially when it comes to national cinemas — that takes the form of a polemical backlash.” While there is nothing quite like a little dogmatic counter-history, WCP offers more than just new ways of considering film history; it’s an invitation to truly view cinema’s flowing rivers, both horizontally and vertically.

Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Project is currently available from The Criterion Collection.