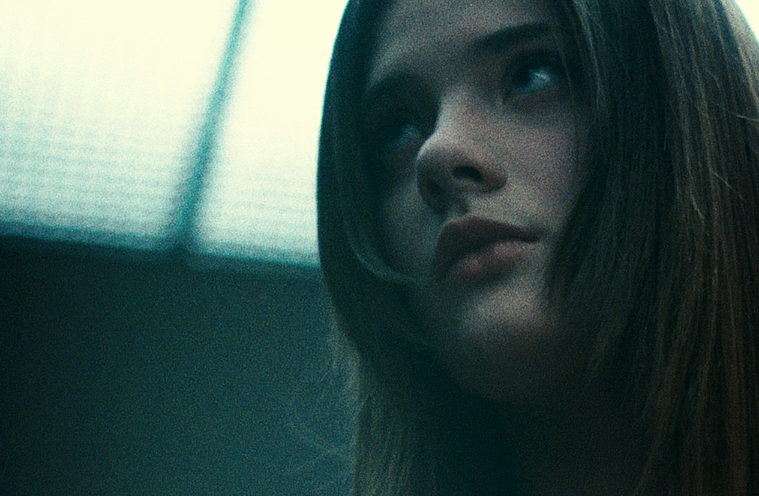

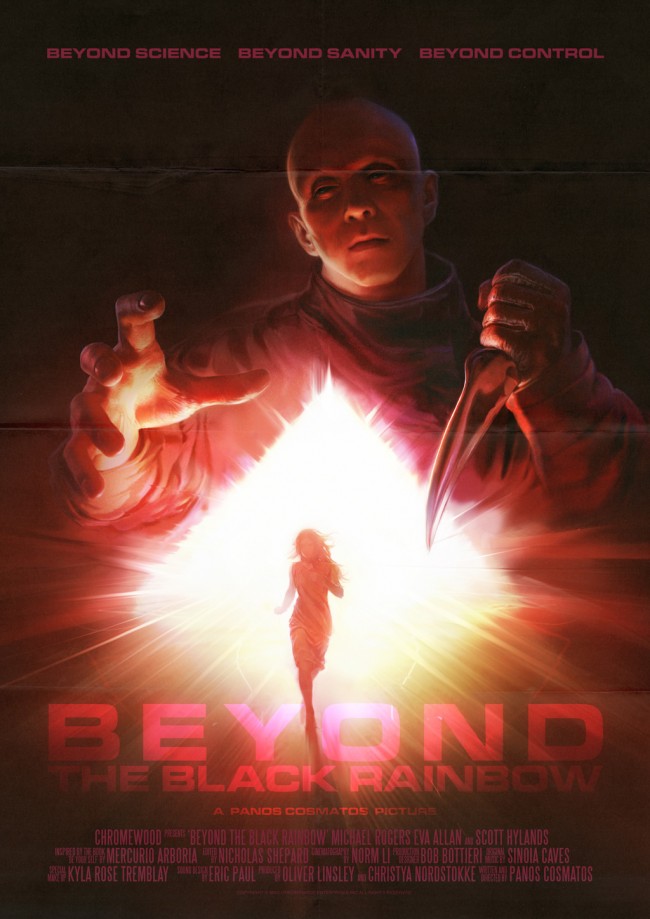

I saw Beyond the Black Rainbow during its international premiere at the 2011 Tribeca Film Festival. Going in, I — as is, purposefully, often the case with festival titles — had almost no idea what to expect, even in terms of a basic plot. To my great joy, the next 110 minutes proved to be an enveloping, horrifying, and funny sensory experience that, in turn, was also one of last year’s more unique cinematic outings.

It’s finally started to make its way out into the world, and we were lucky enough to get a one-on-one chat with Rainbow‘s writer and director, Panos Cosmatos. This is a film that leaves a viewer with so, so many questions, both in terms of overall content and, frankly, just what somebody was thinking when they made it in the first place — so, all things considered, we got a fair deal of information here.

If you want a peek behind Rainbow‘s screenwriting process, hear what encounter with The Shining was a lynchpin in this film’s construction, and know how the helmer of such an esoteric piece could love Prometheus, read below:

I remember, before the international premiere at last year’s Tribeca, you coming out and saying “It’s okay to laugh at certain moments, because much of the humor is intentional.” That set a very good tone for the rest of our screening.

I remember, before the international premiere at last year’s Tribeca, you coming out and saying “It’s okay to laugh at certain moments, because much of the humor is intentional.” That set a very good tone for the rest of our screening.

Panos Cosmatos: Yeah. I just, early on, found that… I had watched the film plenty of times, but I felt that, because the movie’s so… intense, I guess? For lack of a better word; or brooding. It felt like the audience didn’t know they were “allowed to laugh,” or something. You know? So it was just this little thing. The movie’s really funny to me, in a lot of ways, so I just kind of, like… anyways, yeah. Go on.

That’s actually where I’d like to start things off. I wanted to know how you find the right balance between humor and what, I find, are moments of pure terror. I’m not one who’s normally scared by anything in movies, but there are several moments throughout… something about the mood and atmosphere you’re creating here, the way you combine sound and image. So, how does that mixture of humor and horror coalesce in writing, filming, and editing?

Well, I don’t know. I think, maybe, my personality — generally — is sort of a combination of humor and terror, you know? All my life, I’ve dealt with anxiety and terror through humor. But I think, in the film itself, the humor mostly comes out of the characters and how absurd their lives are. I mean, to me, those are some of the funniest moments in the film — the ones that show how absurd and fucked up these people are. And a lot of that just came out of writing the characters.

When you’re writing the characters, do you have any tether to reality? Is it coming from interactions you’ve had, people you’ve met, or is it stemming purely from your imagination?

I think both. Obviously, you’re writing and trying to draw from actual, human interactions, even if it’s in a vague or abstract way. Like, when I was writing Margo, I was thinking of a bank teller I didn’t like, you know? Yeah. Just, like, an unpleasant bank teller, who’s really sort of, like… that’s an emotional reality [Laughs] that can then be, you know, mutated into this absurd environment.

What did you tell your actors? Did they fully understand what they were going for here, or were they entirely at the mercy of your whim?

I tried to give the actors places to start from, and all the actors were, I think, really diligent about trying to create a believable character. The actor that I talked to most, in detail, about how to approach the character was Michael [Rogers], because he had to find the right edge or angle in how to approach this character. But Eva [Allan], I barely even spoke to her at all; her initial audition was so primal and right on the money that I didn’t want to overburden her with backstory or ideas of what I wanted the character to be. So I spoke to her very little off of set and just tried to guide her in front of the camera. And the Margo character, the nurse, I just gave her very simple directions, like beforehand I think I just told her that “you’re a bitchy bank teller.”

Did you have a lot of specifics in mind when writing the actually script? I find that the movie… it’s not that there aren’t answers to the questions raised, but it deals in this somewhat “vague” storytelling, in terms of the main character’s true origin, the nature of this company, or some this girl’s powers —

Yeah, in my mind and, like, in my notes, I tried to make the world as specific and concrete as possible. Then I decided to sort of “mute” or tone down a lot of the story elements, so that the mood of the film would come to the forefront, and the sort of hypnotic element would come to the forefront. And I didn’t want to get too specific, becuase I would hope the film would operate as, like, a moving Rorschach test, where people would project their own anxieties or personal experiences onto these sort of archetypes, and then it would live in that kind of realm; more than a very rigid storytelling realm.

I mean, I had this experience where I watched The Shining in a theater — in a repertory theater at a midnight show — and the speakers were terrible, the sound was cranked super loud, and it was just very “tinny” and “aggressive” sounding. And I had, like… as I was watching the film, I started to see Jack Nicholson as my father, Shelley Duvall as my mother, and myself as a kid, when I was a kid. The whole thing became, like, a metaphor — a very heightened, bizarre metaphor for my family life — and I kind of wanted the film to function in a similar way to that experience, where it was oblique enough for people to project their own lives onto it. I know that’s a lot to ask. [Laughs]

I was really surprised when I read, after seeing the film, that your father, George P. Cosmatos, was also a director — but he made very films very different from your own. He worked with Sylvester Stallone a couple of times, for instance. I would’ve never made the connection between your work, so I have to ask: Did your father serve as any kind of creative influence, even in a possibly indirect way?

If any of his films influenced me at all, it would be Unknown Origin, which is the first movie he made after he moved to Canada — and it’s still my favorite one. It’s the one, from a creative perspective, that I can relate to the most; the themes are the most interesting to me. It’s almost like a J.G. Ballard-esque story about a yuppie versus a rat. But, I don’t know. When me and my father connected, all of our bonding was through our mutual love of movies, you know?

My best memories of him are watching movies with him and talking about them afterwards. And, growing up, he had this giant collection of Beta tapes that he recorded off the Z Channel and HBO; like, thousands of movies that, throughout my life, I was able to watch. It was kind of like a library that I could dip into from every different era.

What were some of those films?

I remember that the one I watched, probably the most, was The Road Warrior. I also had a strange experience where my parents were having a dinner party one night, so I went to the tapes downstairs in the TV room; I wanted to watch, like, a Bob Hope movie. And, so, I popped in this Bob Hope movie — I can’t remember which one it was; some tropical comedy — and the movie started playing. Ten minutes in, those scan lines happened, the static came on, and Barbarella came on. I don’t know if you’ve seen Barbarella, but there’s this scene where she encounters these horrible little dolls that had sharp teeth.

So, I remember being downstairs, in the TV room, alone, thinking I was going to watch this little, light, frothy Bob Hope movie — suddenly, I’m plunged into this psychedelic netherworld of Barbarella and these, like, demonic fucking dolls. That totally scared the living shit out of me.

Has this movie’s release planted the seed for any future projects?

Well, I’m writing something that I think will be the next thing I do; it’s sort of the flip-side to the coin of this movie. This is about repression and control of emotions, and what I’m interested in doing now is sort of the flip-side of the coin, sort of a primal explosion and expression of emotion.

Is that on a bigger scale, or would you say it’s about the same as Rainbow?

Bigger? I don’t know. Yeah, it’s a bit bigger.

I have to ask while the opportunity’s still present: I was surprised to see you tweet your love of Prometheus.

Did you hate it? [Laughs]

No, no, but I just… this film and that film are very different, but you both deal in, again, “vague” storytelling. Do you simply find more value in that? After all, you had a specific outline for Beyond the Black Rainbow that was later toned down. And, also, were you surprised to see a big-scale movie like Prometheus use it?

Yeah, I was thrilled to see a movie like that. I think one of the strongest aspects of Prometheus is that it doesn’t over-explain a lot of its themes or its plot elements — but I think it “does.” I think it just expresses them in a very intelligent, lean way that didn’t pander too much to the audience, you know? I actually think that that film felt dense with information, it’s just that a lot of the information was expressed visually or subtly. I think everything is in there, it’s just not shoved down your throat.

Something like The Avengers I was fascinated by, because there’s a lot of plot beats in that film that they really downplayed — especially for a film like that, where they really tend to overplay any emotional beat or plot beat. And that film worked for me in a lot of ways, too, for the same reason: they underplayed things which, at least recently, studio films tend to shove down your throat.

Do you have any projects developing outside the world of film?

I just want to focus on making movies. You know, I spent enough time in my life wasting time, so what I really care about is movies now. That’s just what I’m going to focus on for now.

Beyond the Black Rainbow is currently playing in limited release.