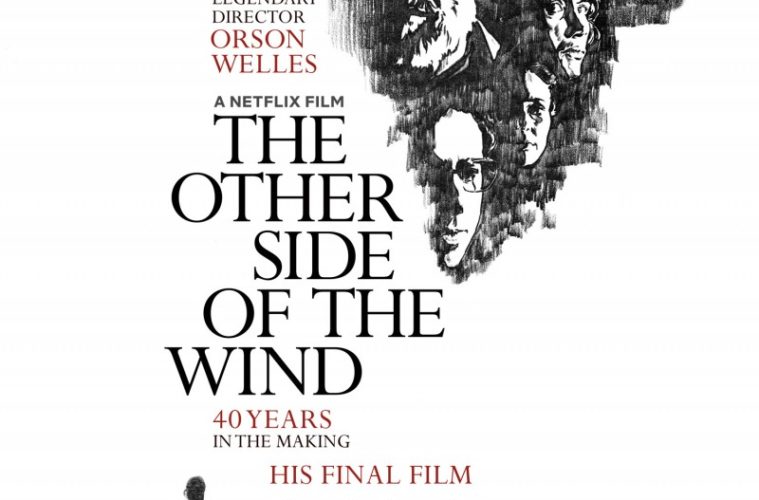

Never had the Netflix logo been welcomed by Venetian audiences with an applause as rapturous as the one it received when the iconic N popped up to introduce what was rightly billed the cinematic event of the year: Orson Welles’ much-awaited and finally restored The Other Side of the Wind.

It was a moment 48 years in the making. In 1970, Welles grouped together a cast of Hollywood giants (including John Huston, Peter Bogdanovich, and Susan Strasberg) to shoot what would turn out to be an eerily auto-fictional farewell opus. Beset by all sorts of financial constraints, the production would stretch, stall, and come to an infamous end. Rejected by major Hollywood studios, partly funded by Iranian production company Apostrophe until the 1979 Revolution — at which point the film effectively became property of the Ayatollah Khomeini and the people of Iran — The Wind would outlive Welles (who passed away in 1985) as an irreparably unfinished last work. Over a thousand reels languished in a Paris vault until 2017, when Netflix heeded the call of producers Frank Marshall, (Welles’ production manager at the time of the initial shooting) and Filip Jan Rymsza, who spearheaded efforts to restore the late Welles’ last work. Calling the feeling that thrummed through Venice’s Sala Darsena on the night of August 30 “a buzz” is an understatement.

The Other Side of the Wind follows legendary US director J.J. “Jake” Hannaford (John Huston) as he returns from a self-imposed exile in Europe to Los Angeles, where he plans to finish his much-awaited comeback film. Packs of admirers, reporters, critics, old-time friends, and colleagues flock to Hannaford’s villa on the night of July 2, where the director throws an alcohol-fueled 70th birthday party that stretches all throughout the night. Marooned between a critique of Hollywood studios, the New Hollywood voices, and the revered European maestros (everyone getting their fair share of mocking), Wind is a chronicle of that feast. Very little action happens (with a few notable exceptions, one involving Huston, plenty of drinks, a rifle, and some mannequins), and plot points are scarce: people chat, get drunk, argue, and drink more.

Towering atop the crowd swarming around Hannaford is emerging director Brooks Otterlake (Peter Bogdanovich) and caustic critic Julie Rich (Susan Strasberg). Otterlake is Hannaford’s protégé, and there’s an intricate father-son relationship entangling the two, Bogdanovich begging for Huston’s approval with so much subtle intensity by the time the young man asks the grizzled maestro “what did I do wrong, daddy?” the epithet sounds poignantly plausible, all the more so when read as a self-comment on Bogdanovich-Welles’ own relationship, one fraught with jealousy and envy. “The only direction Orson gave me was: it’s us,” Bogdanovich recalled Welles instructing him before delivering that line, with an imploring disbelief and heart-wrenching affection The Other Side of the Wind never quite reaches again.

It is not the only moment of auto- and meta-fiction. Critic Rich spends her night juggling with drinks, pen and paper, casting doubts on Hannaford’s genius the way Pauline Kael did in her 1971 New Yorker take on Citizen Kane. And Hannaford himself reeks of a uber-mensch machismo reminiscent of Hemingway, a maverick author who had gone through a post-mishap comeback of his own (the Nobel-winning The Old Man and the Sea dissipating all doubts around Papa’s artistic health after the misfire Across the River and into the Trees), and with whom both Hannaford and The Other Side of the Wind are intimately connected. Long before he gets billed as “the Hemingway of cinema,” (as a party guest refers to him in the middle of the late-night bonanza), Hannaford’s character was meant to feature in a project Welles had begun to toy with ever since getting into a fight with Hemingway in 1937. The plot, later titled The Sacred Beasts, shaped up around an aging novelist who’s lost his creative verve and travels to Spain to trail behind a handsome young bullfighter he’s infatuated with — while running away from a crew of acolytes, critics and students who haunt him throughout the journey. The Sacred Beasts never took off (among its relics is Albert and David Maysles’ short film Orson Welles in Spain, portraying Wells as he pitches the film to a group of affluent folks in Madrid), and the writer in decline-cum-bullfighting aficionado eventually merged into cantankerous, vicious and achingly lonely cineaste “Jake” Hannaford, whose birthday falls the same day Hemingway shot himself dead: July 2, 1961.

Armed with drinks, a cigar dangling from his mouth, Hannaford asks his friends to document the party, and the feeling is to witness a tapestry of behind-the-scenes surveillance footage, the camera shifting from one chat to the next in a night-long stream of consciousness, booze, and arguments. To enter The Other Side of the Wind is to mend through a two hours-long cacophony of sounds and colors, a party of forking storylines endlessly crisscrossing each other: Hannaford and Otterlake’s; Hannaford’s comeback film — a cat-and-mouse silent arthouse feature parodying Antonioni’s Zabriskie Point and starring Welles’ own partner, Oja Kodar — snippets of which are screened to dozens of dumbfounded guests; Hannaford’s hunting down his lead actor and wrestling with his solitary debacle as the party enters its climax.

For all its jumbled narrative, that The Other Side of the Wind’s labyrinthine structure still feels somewhat cohesive is nothing short of a miracle. Editor Bob Murawski (who toggled between 16mm, 35mm, black-and-white and color) and sound editor Daniel Saxlid (who reconstructed damaged or nonexistent dialogues from outtakes, words, and syllables) are the real heroes here: for a dialogue-driven movie where much of the conversations had gone amiss, the script a convoluted and elliptical bundle of notes, and no chances of re-recording the cast, working to resuscitate Welles’ vision must have felt like putting together a puzzle without knowing its shape or number of pieces.

But the work paid off. The Other Side of the Wind is not a comeback picture in the sense Touch of Evil was supposed to be. It is a confounding, unsettling, disorienting adieu from a director whose nonconformist and uncompromising vision was decades ahead of his time. Venturing into it is to embark on an entrancing, kaleidoscopic journey — a quintessentially Wellesian seesaw between fiction and truth. Minutes before a melancholic finale, the party guests watching Hannaford’s film at a nearby drive-in theater, Otterlake runs toward the projectionist in horror: “Someone must have given you the wrong reel!” Indifferently, the man replies with a shrug. “Does it matter?”

The Other Side of the Wind premiered at Venice International Film Festival and hits Netflix and select theaters on November 2.