Who needs a middle man’s subjectivity when you have algorithms predicting what people will like? Critics don’t matter much in Olivier Assayas’ talkative Non-Fiction, but they are not the only supposedly anachronistic relic to be thrown out of the window in this gentle and profoundly compassionate human comedy that draws from the ever-widening rift between old and new trends in the publishing industry to conjure up a tale of societal changes and those caught in between them.

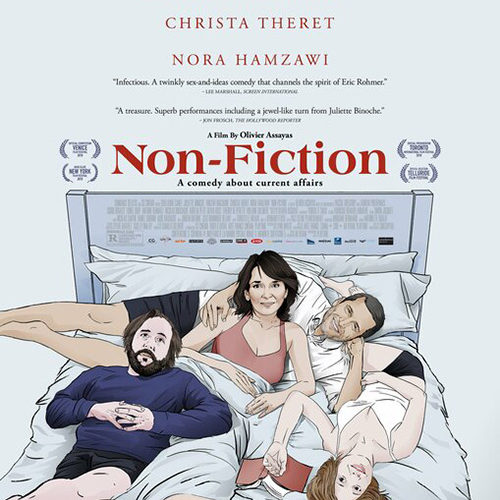

Nurturing a collaboration that fathered prior gems such as Summer Hours and the more recent Clouds of Sils Maria, Non-Fiction adds another entry to the list of Assayas–Binoche duets, the French muse still starring as an actress — albeit downgraded from the Clouds’ arthouse charmer to policewoman (or “crisis management expert,” as she likes to remind dinner guests) in a TV series of dubious quality. But Juliette Binoche no longer serves as the plot’s gravitating center, instead sharing the spotlight with the three other members of a quartet comprising her well-established publisher husband Alain (Guillaume Cantet), her friend-cum-lover writer Léonard (Vincent Macaigne), and Léonard’s own partner Valérie (Nora Hamzawi).

Years after a first hit, Léonard’s writing career is heading to a twilight (“my other books have been worst-sellers,” explains Macaigne in one of many moments of comedic brilliance, “I don’t want to add more to the deforestation”). He’s submitted his latest offering to his friend and old-time publisher Alain, who politely rejects the manuscript, billing it as “more of the same” from an author whose auto-fictional romans-à-clefs have lost steam. Binoche’s Selena disagrees, though it’s hard to tell just how much her support for Léonard’s literary endeavors may be entangled with their ongoing affair. Unbeknownst to Alain, Selena cheats on him, foraging the writer’s pantheon of sexual conquests-turned-characters; unbeknownst to Selena, Alain cheats on her, too, sleeping with Laure (Christa Théret), a digital strategist he’s hired to modernize the publishing company — a crusade Assayas’ script translates into a battle to steer away from print and open the doors to the world of e-books and online publishing.

The prospect of sitting through endless dinner parties where affluent bourgeois debate the future of literature only to quietly backstab each other in a merry-go-round of extramarital liaisons may not exactly sound promising, but Non-Fiction turns the cauldron into a delightful ride, and if the aftertaste is one of cinematic delight — the feeling of being invited to take part in those chats, not just to listen to them — credit goes to Assayas’ writing and a handful of phenomenal performances from the quartet and supporting cast.

Yes, people do talk ad nauseam in Non-Fiction, but the chats never give in to a self-absorbed and self-referential intellectualism; even when characters drop some serious film references, the innuendos are either cast in a delightfully funny light or underscore some existential concerns with a heartfelt, compassionate voice. There is a memorable scene where Léonard says he wrote a sex scene based on a movie-theatre blowjob he received a few years prior — but he swapped the blockbuster he saw (Star Wars: The Force Awakens) for an arthouse masterpiece (The White Ribbon). Chuckles abound in Non-Fiction — finding in Macaigne a shaggy-looking, irresistible comedic epicenter — but they coexist with philosophical musings of far graver depths.

In a pivotal juncture, Alain confronts Laure’s digital revolution and print Armageddon with a reference to Bergman’s Winter Light (which, of course, the sleek and ruthless digital poster-girl has never seen), casting himself as the lone priest who, “even when the church is empty,” keeps believing. It may reek of self-aggrandizing narcissism, but while a certain aversion for All Things Millennial does reverberate throughout Non-Fiction, Alain’s repulsion and fears for the changes brought about by a new generation feel tangible precisely because Assayas never mocks the youngsters challenging the establishment, but allows them ample time to formulate pertinent arguments which Alain, in his quixotic and nostalgic battle to safeguard the integrity of traditional publishing, is ill-prepared to fight. How do you argue for the sake of print books if their prices make them unaffordable to the masses? And how can you gloss over the democratizing potential of an all-digital publishing world?

Non-Fiction is a symposium of sophisticated and timeless musings that span from the future of e-books to the ethics of auto-fiction. But it’s a defying and precious charmer: in a plot that, judged from its cover, should promise close to two hours of pretentious navel-gazing, it steers clear from any traces of it, crafting a comedy whose four protagonists add to their own philosophical ramblings a compelling mix of warmth, candor, and fallibility.

“Everything must change for things to stay the way they are.” The famous line Tancredi Falconieri utters in The Leopard ricochets around the conversations between Cantet, Binoche, Macaigne, Hamzawi, and Théret. It is echoed by another leitmotiv that runs through their endless, alcohol-fueled dinners, this one the four process with an alarming look: “We’re at a tipping point.” They are all scared to look at what lies ahead — and in Non-Fiction‘s empathetic human comedy, their worries are immediately relatable.

Non-Fiction premiered at Venice International Film Festival and opens on May 3.